Making minerals: Crushed, zapped, boiled and baked

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen the penguins poop on Antarctica's Elephant Island, a little bit of magic happens in the soil.

Chemical reactions produce a dull brown mineral called spheniscidite. It's unique and reflects the special conditions that exist only in that locality.

The name comes from Sphenisciformes - the label used to describe penguins' grouping in the avian tree of life.

The crystalline compound is just one of roughly 6,000 such minerals recognised today by the International Mineralogical Association.

But the IMA's classification system, which describes so much of the "hard stuff" all around us, has just undergone something of a reboot.

Dr Robert Hazen from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington DC has spent the past 15 years reclassifying the minerals to add information about their genesis.

"There's been a classification system in place for almost two centuries that's based on the chemistry and the crystal structure of minerals, and ours adds the dimensions of time and formation environment," he told the Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service.

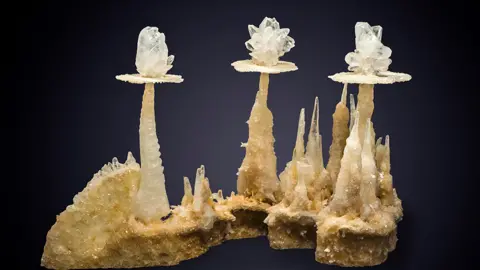

ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky

ARKENSTONE/Rob LavinskySimply put, minerals are specific combinations of chemical elements arranged into an ordered, crystalline form. All of Earth's rocks are built from different aggregations.

You'll know some of the most common ones, such as feldspar, quartz and mica, which make up the granite in a kitchen worktop.

But with colleague Dr Shaunna Morrison, the Carnegie Institution researcher has tried to give the thousands of different mineral species some extra context.

The point the pair are making is that you can't truly appreciate the significance of a mineral unless you also understand how and when it formed. Their research shows nature has used 57 "recipes" to create 10,500 of what they like to call "mineral kinds" - by crushing, zapping, boiling, baking and more.

Water, they say, has helped more than 80% of mineral species to form.

Biology has had a direct or indirect role in the creation of about 50% of mineral species.

One-third of mineral species formed exclusively through biological processes.

ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky

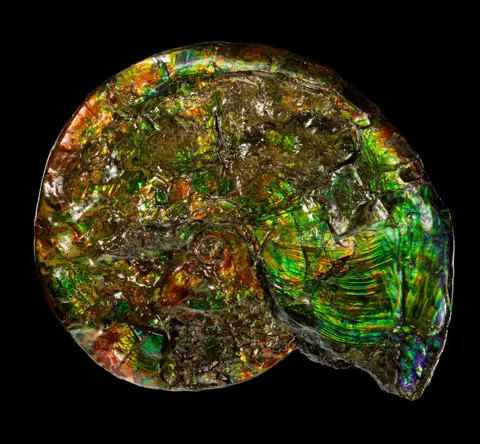

ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky"Life affects minerals in various ways," explained Dr Hazen.

"For example, photosynthesis produces oxygen. Oxygen is a very reactive gas, and it changes the surface of Earth by oxidising minerals. So more than 2,000 new minerals formed on Earth as a result of oxygen in the atmosphere. But of course, life also creates its own minerals, biominerals.

"These are shells, teeth, bones, and other structures in organisms that are purposefully deposited and sculpted in the most amazing nano-technology kinds of ways.

"Scientists and engineers would love to be able to reproduce what life is able to do."

ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky

ARKENSTONE/Rob LavinskyHazen's and Morrison's work is summarised in twin papers published by the international journal American Mineralogist.

The pair have built a database of every known process of formation for every known mineral species. That's 5,659 in the IMA catalogue.

For each mineral, the duo detail the recipe used; the particular physical, chemical or biological process involved - and combinations thereof.

- 40% originated in more than one way

- 3,349 (59%) occur through just one process

- 9 came into being via 15 or more ways

- Pyrite (Fool's Gold) formed in 21 ways

Dr Hazen said: "The previous system of mineralogy said calcite is calcite; that's calcium carbonate in the calcite crystal structure, that's a species. But we say no, no, no - there are 10, 15 maybe 20 different kinds of calcite, because the calcite deposited by a shell is very different from the calcite that forms on the ocean floor through just chemical precipitation, or calcite formed deep within the Earth in a process of metamorphism - of high pressure and high temperature.

"So, we see many different kinds of calcite, and that's key to our new approach to mineralogy."

ARKENSTONE/Rob Lavinsky

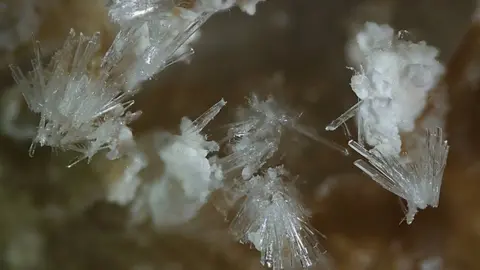

ARKENSTONE/Rob LavinskySome minerals are extraordinarily ancient; 296 are even thought to pre-date Earth itself. Of this number, 97 are known only from meteorites. These can include mineral grains with ages estimated at up to seven billion years. That's long before our Solar System existed.

At the other extreme are the mineral whippersnappers that totally owe their existence to just a few centuries of human industrialisation. For example, there are 500 or so minerals that are the direct result of mining activity; 234 of these are produced in coal mine fires.

Hazen's and Morrison's work not only puts the mineralogy of Earth into its proper historical context, it also becomes a tool to investigate other worlds.

"We're looking at the mineralogy of Mars," said Dr Hazen. "We're constantly looking for evidence in the minerals that might point to life.

"If we find it, it's not going to be that we find one particular species of mineral; it's going to be the trace of minor elements, the morphologies, the sizes and shapes of these minerals. It's their local associations that's going to be the smoking gun for life on Mars."

R.HAZEN

R.HAZEN