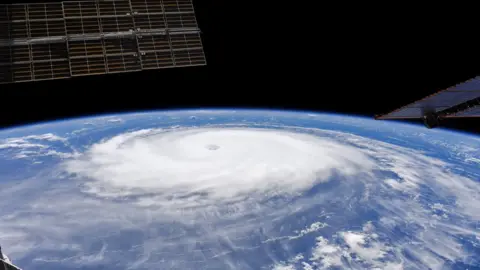

Forecasters predict a very active hurricane season

NASA

NASAForecasters predict another very active hurricane season this year.

This is because for a second consecutive winter weather patterns will be heavily influenced by a natural phenomenon known as La Niña.

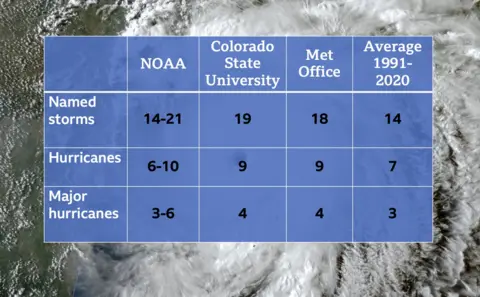

Scientists from NOAA, the US weather service, have released the official outlook for the hurricane season which runs from June through to November.

It backs up forecasts from Colorado State University and the UK's Met Office.

All suggest above average numbers of named storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes.

It follows last year's third most active season on record and 2020's most active season on record when all pre-determined names were exhausted with the Greek alphabet needing to be used.

The outlook for the 2022 season would make it the seventh consecutive above-average hurricane season.

Forecasters from Colorado State University suggest there is a 70% chance of at least one major hurricane (category 3 or higher) hitting the continental US coastline. The long-term average is a 53% chance.

Why another active season?

Forecasts are based on a number of factors but one of the most influential is the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

This is a naturally occurring weather pattern in the eastern Pacific which has implications on the weather across the world.

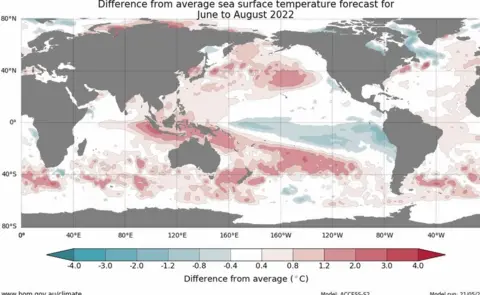

It refers to changing trade winds and sea surface temperature in this region with a warmer than average El Niño, cooler than average La Niña and a neutral phase.

AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF METEOROLOGY

AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF METEOROLOGY La Niña can mean a more active hurricane season because it reduces wind shear - the sudden change of wind speed and/or direction - high up in the atmosphere allowing tropical storms to develop more readily.

NOAA forecasters suggest the other factors contributing to the increased activity are warmer than average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds and an enhanced west African monsoon.

Double-dipping La Niña?

La Niña has been observed over the last two winters, known in the meteorological community as a double-dip. Since records began in 1950 this has only occurred eight times before.

According to forecasts from NOAA and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, there is nearly a 60% probability of La Niña persisting or becoming slightly neutral throughout the hurricane season.

Some computer models even suggest a neutral or La Niña-like state through to the northern hemisphere winter, making it a very rare 'triple-dip'.

This has happened only twice before since records began. It will have an impact on the 2023 hurricane season, and with La Niña affecting other weather patterns around the world will have consequences further afield.

La Niña has been a major factor in the devastating floods in eastern Australia this year and the severity of the ongoing drought in California.

It is worth pointing out though that while a triple-dip La Niña looks like a possibility, the accuracy of ENSO forecasts in the Spring is questionable so it's far from a certainty.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIs there a link to climate change?

With another active season expected many might question whether climate change has had a hand in this.

As the main driving force for tropical storm and hurricane development is the naturally occurring El Niño Southern Oscillation pattern, scientists suggest climate change is not pivotal for an increase in storms.

However, with the other factor of storm development being warmer than average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and Caribbean, this could have an impact.

With warmer oceans there is more fuel available for a storm to develop and intensify rapidly. According to the IPCC there is "high confidence" that the proportion of intense tropical cyclones will increase on a global scale with increasing warming.