Climate change: Can the UK afford its net zero policies?

Getty Creative/Philip Silverman

Getty Creative/Philip SilvermanWith the cost of living rising, are Britain's plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions too expensive?

A small but vocal group of Conservative MPs are arguing that with energy prices soaring, the government should rethink how it reaches what's known as 'net zero' by 2050.

The group has made a number of key arguments. So what are they saying, and what does the data tell us?

Three years ago the goal of net zero was written into UK law with the backing of MPs from all sides.

Broadly speaking it's a commitment to transform the way our economy operates. Net zero means not adding to the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Achieving it means reducing emissions as much as possible, as balancing out any that remain.

There's consensus among the world's scientists that it's vital if we're to have a chance of keeping global temperature rises to manageable levels.

What are the MPs trying to achieve?

MPs office

MPs officeThe Net Zero Scrutiny Group is made up of about 20 Conservative MPs and peers and was set up last summer by prominent Eurosceptics Craig Mackinlay and Steve Baker.

In a letter published in the Telegraph in January the group argued that while the rise in the global cost of gas was contributing to the crisis, the UK government was causing energy prices to increase "faster than any other competitive country" through "taxation and environmental levies".

In the weeks that have followed there have been a steady flow of articles in sympathetic newspapers, questioning the logic behind the net zero strategy.

The NZSG argue that the price of reaching net zero is too great, the plans too hasty, and that Britain in 2022 is not in a position to afford it.

"It would be more sensible to 'backload' Net Zero closer to 2050 than 'frontload' now as we're attempting to do," Mr Mackinlay told BBC News in an email.

That's at odds with the Treasury's Office for Business Responsibility which says that delaying decisive action on climate change by ten years could end up doubling the total cost.

The NZSG says it doesn't question the science of climate change.

But some of its members have close links to think tanks that have long queried the scientific consensus on global warming, and the necessity and cost of doing something about it.

Mr Mackinlay told the BBC that the role of the group is to "scrutinise" and to focus on "energy security, affordability, practicality; are the vulnerable protected and is there a better way?"

How much of the increased price of gas and electricity is due to 'green' policies?

Analysis from Carbon Brief shows that 87% of the increase that will appear in the typical UK energy bill this April is down to the massive rise in global gas wholesale prices. Most of the rest of the hike will come from costs associated with gas suppliers going out of business.

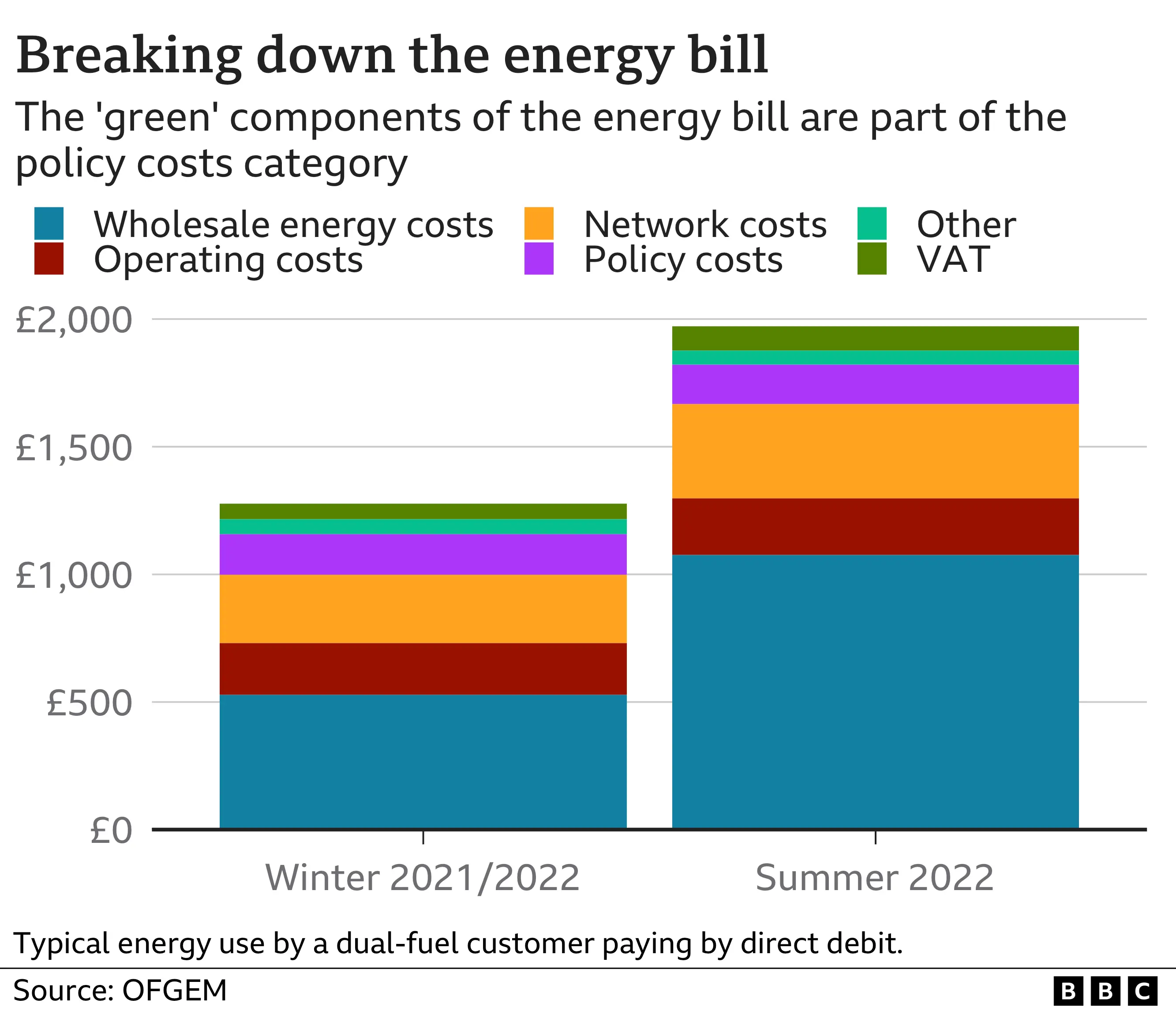

This breakdown from energy regulator Ofgem shows how the 'green' part of your bill is included in what's known as Policy Costs and has stayed relatively stable. This levy is spent on a mix of social and environmental policies and includes things like supporting energy efficiencies in low-income households. For customers who pay for their gas and electricity together in a dual-fuel deal, with the price cap in place, that Policy Cost will fall in April from £159 (12% of the bill) to £153 (8%).

Would it be cheaper and more reliable to build gas or nuclear power stations instead of renewables?

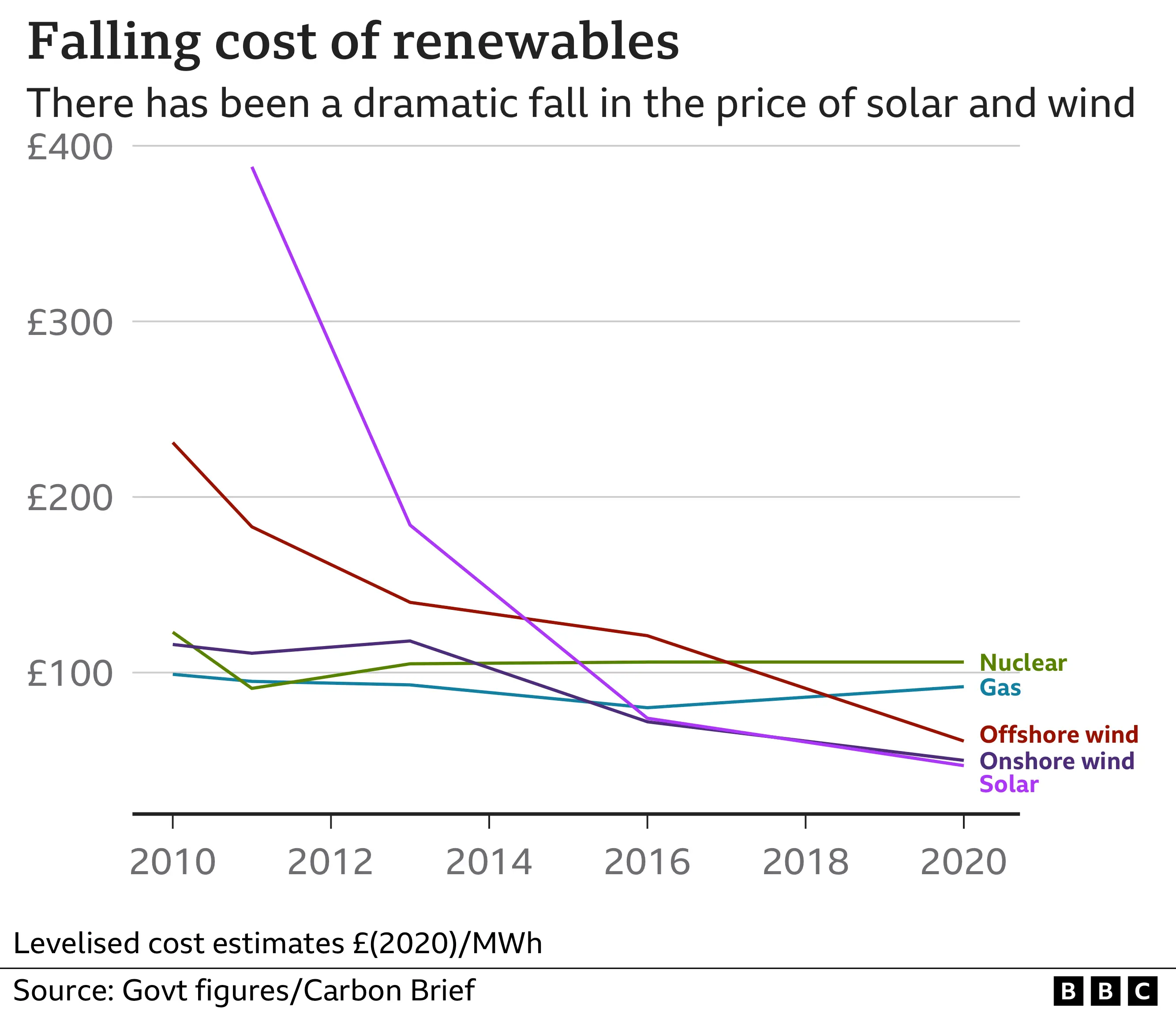

The economics of electricity generation have dramatically changed in the last decade. Technological advances and economies of scale mean renewables have gone from being heavily subsidised to now being the cheapest option for new projects. In 2020 a record 43.1% of the UK's electricity came from renewable sources.

The cost of different forms of energy can be compared using what's known as the "levelised cost" which takes account of the cost to build and operate a power station and how long it will be operational for.

There's also the question of how Britain is going to keep the lights on when the wind doesn't blow and the sun isn't shining? The technology doesn't yet exist to store sufficient amounts of power. Most agree there needs to be a back-up, such as nuclear or gas, at least in the medium term for when the output from renewables falls.

This has lead to calls from the Net Zero Scrutiny Group and others for more gas to be extracted domestically and used as a "transition" fuel while nuclear capacity is rebuilt.

A particular focus of the NZSG has been a push to get fracking for shale gas restarted.

Fracking is way of extracting gas by firing a high-pressure water and chemical mixture into rocks underground. After several small earth tremors and widespread local opposition a moratorium on fracking was introduced in the UK in 2019.

Would our gas be cheaper if we fracked?

Fracking's supporters in the UK look enviously towards the United States. A fracking boom there has meant a huge increase in gas supply, and prices are comparatively low. But the physical geography and market conditions of the UK and the US are very different. America is largely isolated from global gas markets, Britain very much connected.

"The UK operates in a global interconnected market for gas, where it is competing with other European countries for pipeline gas from the North Sea and for LNG (liquefied natural gas)," says Simon Evans of Carbon Brief.

"Domestically produced gas would be feeding into that market and, barring export controls, would be sold to the highest bidder on the market."

Craig Mackinlay of the NZSG agrees that international prices would still apply to the UK but argues that a domestic fracking industry would bring "huge benefits", help "levelling up" and stop reliance on gas from "hostile regimes" like Russia.

There are varying estimates over how much shale gas could be extracted and how many jobs it would actually create but this analysis from the London School of Economics suggests that fracking's supporters are overly upbeat.

The frackers' biggest obstacle would appear to be public opinion. Local opposition led to the fracking ban and a recent survey put support for fracking at just 19%.

How much is the goal of net zero by 2050 costing the UK?

The numbers are huge. In July last year the UK's Office for Budget Responsibility costed the government's "Balanced Net Zero Pathway" and came up with a figure of £1.4tn (at 2019 prices).

But that £1.4tn cost will be spread over three decades. When combined with savings from things like more energy-efficient buildings and vehicles, the OBR says the net cost to the state up to 2050 will be £344bn in real terms. This represents an average of 0.4% of GDP a year. Defence spending by comparison is about 2.1% of UK GDP.

What might be the cost of doing nothing?

The UK government's latest report into the risks of climate change warns that based on a conservative estimate of a 2C temperature rise by 2100, flooding for non-residential properties across the UK is expected to increase by 27% by 2050 and 40% by 2080. At 4C this increases to 44% and 75% respectively.

The report estimates that for eight risk factor areas, which include things like food supply and human health, the cost under one of the optimistic scenarios of a rise of less than 2C, could exceed £1bn a year by 2050.

Two prominent studies have projected losses of between 7 and 23% of global GDP by the end of this century if emissions are not rapidly cut, as rising temperatures lead to falls in both labour and agricultural productivity.