Neanderthal extinction not caused by brutal wipe out

BBC

BBCNew fossils are challenging ideas that modern humans wiped out Neanderthals soon after arriving from Africa.

A discovery of a child's tooth and stone tools in a cave in southern France suggests Homo sapiens was in western Europe about 54,000 years ago.

That is several thousands of years earlier than previously thought, indicating that the two species could have coexisted for long periods.

The research has been published in the journal Science Advances.

The finds were discovered in a cave, known as Grotte Mandrin in the Rhone Valley, by a team led by Prof Ludovic Slimak of the University of Toulouse. He was astonished when he learned that there was evidence of an early modern human settlement.

"We are now able to demonstrate that Homo sapiens arrived 12,000 years before we expected, and this population was then replaced after that by other Neanderthal populations. And this literally rewrites all our books of history."

Rob Hope Films

Rob Hope FilmsThe Neanderthals emerged in Europe as far back as 400,000 years ago. The current theory suggests that they went extinct about 40,000 years ago, not long after Homo sapiens arrived on the continent from Africa.

But the new discovery suggests that our species arrived much earlier and that the two species could have coexisted in Europe for more than 10,000 years before the Neanderthals went extinct.

According to Prof Chris Stringer, of the Natural History Museum in London, this challenges the current view, which is that our species quickly overwhelmed the Neanderthals.

"It wasn't an overnight takeover by modern humans," he told BBC News. "Sometimes Neanderthals had the advantage, sometimes modern humans had the advantage, so it was more finely balanced."

Archaeologists found fossil evidence from several layers at the site. The lower they dug, the further back in time they were able to see. The lowest layers showed the remains of Neanderthals who occupied the area for about 20,000 years.

But to their complete surprise, the team found a modern human child's tooth in a layer dating back to about 54,000 years ago, along with some stone tools made in a way that was not associated with Neanderthals.

The evidence suggests that this early group of humans lived at the site for a relatively brief period, of perhaps about 2,000 years after which the site was unoccupied. The Neanderthals then return, occupying the site for several more thousand years, until modern humans come back about 44,000 years ago.

Ludovic Slimak

Ludovic Slimak''We have this ebb and flow,'' says Prof Stringer. ''The modern humans appear briefly, then there's a gap where maybe the climate just finished them off and then the Neanderthals come back again.''

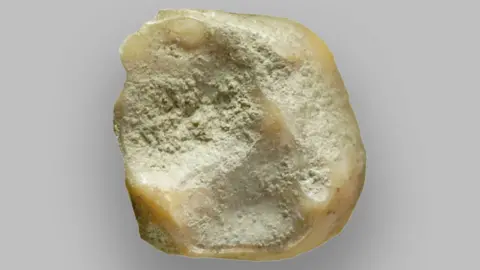

Another key finding was the association of the stone tools found in the same layer as the child's tooth with modern humans. Tools made in the same way had been found in a few other sites - in the Rhone valley and also in Lebanon, but up until now scientists were not certain which species of humans made them.

Ludovic SlimaK

Ludovic SlimaKSome of the researchers speculate that some of the smaller tools might be arrow heads. If confirmed, that would be quite a discovery: an early group of modern humans using the advanced weaponry of bows and arrows, which may have been how the group initially overcame the Neanderthals 54,000 years ago. But if that were the case, it was a temporary advantage, because the Neanderthals came back.

So, if it wasn't a case of our species wiping them out immediately, what was it that eventually gave us the advantage?

Many ideas have been put forward by scientists: our capacity to produce art, language and possibly a better brain. But Prof Stringer believes it was because we were more organised.

"We were networking better, our social groups were larger, we were storing knowledge better and we built on that knowledge," he said.

The idea of a prolonged interaction with Neanderthals fits in with the discovery made in 2010 that modern humans have a small amount of Neanderthal DNA, indicating that the two species interbred, according to Prof Stringer.

"We don't know if it was peacefully exchanges of partners. It might have been grabbing, you know, a female from another group. It might have been even adopting abandoned or lost Neanderthal babies who had been orphaned," he said.

"All of those things could have happened. So we don't know the full story yet. But with more data and with more DNA, more discoveries, we will get closer to the truth about what really happened at the end of the Neanderthal era."

Follow Pallab on Twitter