Space sleeping bag to solve astronauts' squashed eyeball disorder

BBC

BBCScientists have developed a hi-tech sleeping bag that could prevent the vision problems that some astronauts experience while living in space.

In zero-gravity, fluids float into the head and squash the eyeball over time.

It's regarded as one of the riskiest medical problems affecting astronauts, with some experts concerned it could compromise missions to Mars.

The sleeping bag sucks fluid out of the head and towards the feet, countering the pressure build-up.

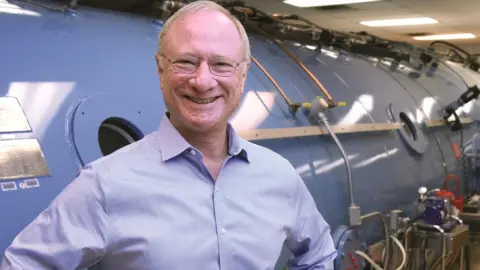

Its development was led by Dr Benjamin Levine, professor of internal medicine at University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who is working on having the device deployed on the International Space Station (ISS).

Nasa has documented vision problems in more than half the astronauts who served for at least six months on the International Space Station (ISS). Some became far-sighted, had difficulty reading, and sometimes needed crewmates to assist in experiments.

"We don't know how bad the effects might be on a longer flight, like a two-year Mars operation," said Prof Levine, who is also director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine, a collaboration between UT Southwestern and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas.

"It would be a disaster if astronauts had such severe impairments that they couldn't see what they're doing and it compromised the mission."

NASA

NASAIn 2005 astronaut John Phillips launched to the ISS with 20/20 vision and came back six months later with his vision at 20/100. Others experience a less severe version of the condition.

On Earth, gravity pulls fluids down into the body each time a person gets out of bed - something known as "unloading". But in space, the low gravity allows more than half a gallon of body fluids to gather in the head, applying pressure to the eyeball.

It can cause a condition called spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome, or SANS. This in turn can lead to progressive flattening at the back of the eyeball, swelling of the optic nerve and vision impairment.

"The pressure in zero-g is always lower than the pressure in one-g. But it's not as low as when you're standing up. That's the problem - normally, we spend one-third of our time lying down at night and two-thirds upright during the day. Nasa astronauts can't stand up during flight," Dr Levine told BBC News.

Even though the brain pressure in a person lying down on Earth is slightly higher than in someone who's in space, astronauts experience this pressure constantly and can never relieve it by shifting to an upright position.

Dr Levine explained: "They never get to unload the brain. So we asked, can we re-introduce a gravitational gradient?"

The sleeping bag, developed with outdoor equipment manufacturer REI, fits around the person's waist, enclosing their lower body within a solid frame.

David Gresham

David GreshamA suction device, that works on the same principle as a vacuum cleaner, creates a pressure difference that draws fluid down towards the feet. This prevents it from building up in the brain and applying damaging pressure to the eyeball.

Several questions need to be answered before the sleeping bag technology is used routinely, including the optimal amount of time astronauts should spend in the sleeping bag each day.

Dr Levine explained: "Does everyone need to do this, or is it just the people who are at risk of developing SANS? Do you need to do it as soon as you get into space, or can you wait and see if your vision changes?"

He added: "That kind of dosing still needs to be worked out."

But Dr Levine says the development means SANS may no longer be a health risk by the time Nasa launches to the Red Planet.

Cancer survivors played a crucial role in clarifying the causes of the condition. The volunteers still had ports in their heads used to deliver chemotherapy drugs, and these allowed the scientists to measure brain pressure while they were flown on parabolic flights that simulate zero-gravity for a few seconds.

A dozen separate volunteers tested the technology itself. Scientists took measurements while they were lying down, with and without the sleeping bag. The researchers found that while just three days of lying flat induced enough pressure to slightly alter the eyeball's shape, no such change occurred when the suction technology was used.

The team at UT Southwestern previously found that microgravity caused the heart to shrink in space and may lead to a condition called atrial fibrillation, where the organ beats in an irregular manner.

It's possible the sleeping bag could also help counteract the abnormal blood flow that increases the risk of an irregular heartbeat in microgravity.

The work has been described in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Ophthalmology.

Follow Paul on Twitter.