Mars: Vast amount of water may be locked up on planet

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSSIt's a longstanding mystery: how Mars lost the water that flowed across its surface billions of years ago.

Scientists now think they have an answer: much of it became trapped in the planet's outer layer - its crust.

The ancient water exists in the form of minerals contained within Martian rocks.

The findings have been discussed at the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference and are published in Science journal.

The study used measurements gathered from Mars-orbiting spacecraft, rovers and meteorites.

Researchers then developed a computer simulation of how water was lost from the planet over time.

More than four billion years ago, Mars was warmer and wetter - possibly with a thicker atmosphere. Water coursed through rivers, cutting channels in the rock, and pooled in impact craters.

The Red Planet could have held enough water to cover its entire surface in a layer measuring between 100m and one kilometre deep.

Around a billion years later, Mars had made the transition to the colder, desolate planet we recognise today.

"We have known for a long time that Mars was much wetter in its early history. But, the exact fate of that water has been an ongoing problem," said planetary scientist Dr Peter Grindrod, who was not involved with the latest study.

Dr Grindrod, from London's Natural History Museum, told BBC News: "We already know from studies of the atmosphere of Mars that some of that water was lost to space, and ice deposits on and just below the surface tell us that some water became frozen."

Escape to space

Earth has a magnetic shield, or magnetosphere, that helps prevent the atmosphere from escaping. But Mars' magnetic shield is weak and could have allowed elemental components of water to escape from the planet.

But the rate at which hydrogen - one chemical constituent of water - escapes from that atmosphere today suggests this can't be the whole story.

If it's assumed that the current loss rate for hydrogen was the same in the past, "it's a pretty small amount of water that you would have lost through this escape process", said co-author Eva Linghan Scheller, from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

In other words, most of the water must have gone elsewhere.

NASA/JPL/JHUAPL/MSSS/BROWN UNIVERSITY

NASA/JPL/JHUAPL/MSSS/BROWN UNIVERSITYThe results of the team's computer modelling work show that between 30% and 99% of Mars' initial water was incorporated into minerals and buried in the planet's crust.

Co-author Prof Bethany Ehlmann, also from from Caltech, explained that, "by studying data from Mars missions, It became clear that it was common - and not rare - to find evidence of water alteration".

She continued: "When the crust becomes altered, it takes water - like liquid water - and sequesters it in a hydrated mineral that has water in its structure so that it is effectively trapped."

The authors suggest that most of the water was lost between about 4.1 and 3.7 billion years ago - during a stretch of Martian history known as the Noachian Period.

Martian climate change

Dr Michael Meyer, lead scientist for Nasa's Mars exploration program, said: "The original overarching role of Mars exploration has been to follow the water, since it plays such a central role in the geology, climate and life of the planet.

"This is a very important paper to understand how much water was on Mars, how it might have been lost and where it might be today."

Dr Grindrod added: "What this new study tells us is that a lot of that water, possibly the majority, could have actually been locked into the rocks on Mars. This process of hydration is capable of storing large volumes of water, up to an amount equivalent to a global layer a kilometre deep."

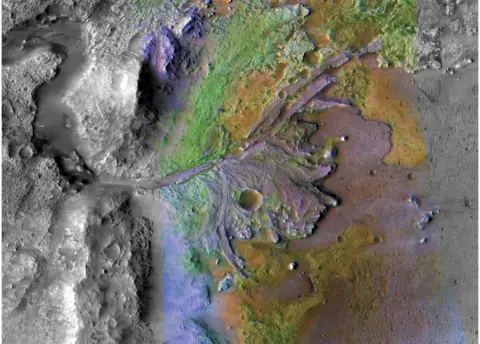

"Although most of the liquid water had probably disappeared after about one and a half billion years after Mars formed, we see evidence of hydrated minerals at the surface today, in areas like Jezero Crater, which is currently being explored by the Perseverance rover.

"The early climate of Mars remains one of the most important topics in planetary science, and this study will help our understanding of the processes responsible for water loss."

Follow Paul on Twitter.