High-altitude birds evolved thicker 'jackets'

Aditya Chavan

Aditya ChavanA study of 250 species of Himalayan songbirds has revealed how their feathers evolved for higher altitudes.

The birds in colder, more elevated environments had feathers with more fluffy down - providing them with thicker "jackets".

The insight reveals how feathers provide the tiniest birds with such efficient protection from extreme cold.

It also provides clues about which species are most at risk from climate change, the scientists say.

The study, in the journal Ecography, was inspired by a tiny bird lead researcher Dr Sahas Barve saw during an icy day of fieldwork in the Himalayas, in 2014.

Victoria Gill

Victoria Gill"It was -10C," said the researcher from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in Washington DC.

"And there was this little bird, a goldcrest, which weighs about the same as a teaspoon of sugar.

"It was just zipping around catching bugs."

Dr Barve's fingers went numb as he tried to take notes.

But he remembers being "blown away by the little goldcrest".

"To survive, this bird has to keep its heart at about 40C," he said.

"So it has to maintain a difference of 50C in that little space.

"I was like, 'OK, I really need to understand how feathers work.'"

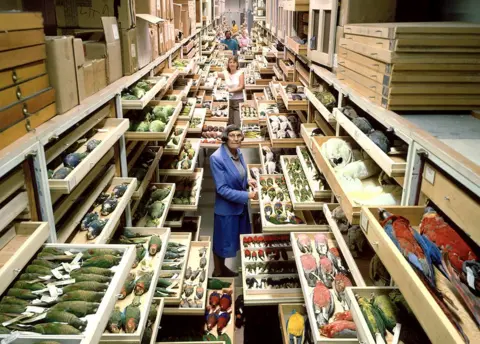

Fortunately, Dr Barve's home institution has one of the largest bird collections in the world.

Examining the feathers of nearly 2,000 individual birds, in microscopic detail, he noticed a pattern linked their structure to their habitat.

Miguel Montalvo/Smithsonian

Miguel Montalvo/SmithsonianEach feather has an outer part and a hidden downy portion.

And Dr Barve's measurements revealed those living at higher elevations had more of the lower fluffy down.

"They had fluffier jackets," he said.

Smaller birds, which lose heat faster, also tend to have longer feathers in proportion to their body size, revealing the little goldcrest's secret.

Dr Carla Dove, who runs the museum's Feather Identification Lab and contributed to the study, said she was excited to use the Smithsonian's collections in a new way.

"Having them all in one place, as opposed to having to go to the Himalayas and study these birds in the wild, obviously makes a big difference," she said.

Chip Clark/Smithsonian

Chip Clark/SmithsonianDr Barve said: "It would take me a decade to go out, find the birds and study their feathers.

"We've been using down jackets for a long time.

"But we haven't understood how those feathers work on a bird.

Sahas Barve

Sahas Barve"We don't know what discoveries our specimens will be used for down the line.

"That's why we have to maintain them and keep enhancing them.

"These specimens from the past can be used to predict the future."

Follow Victoria on Twitter.