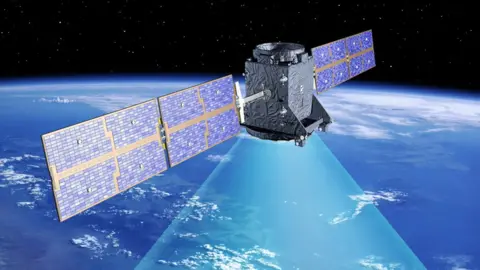

UK industry bids farewell to EU's Galileo system

ARIANESPACE/CNES/ESA

ARIANESPACE/CNES/ESAThe UK's final big industrial contribution to the EU's Galileo sat-nav system has been delivered.

European Space Agency officials confirmed on Thursday that Surrey Satellite Technology Limited of Guildford has shipped the last of the navigation payloads it was assembling.

These payloads are the "brains" of the spacecraft and generate the signals the Galileo network sends down to Earth.

Britain left the project on its departure from the EU.

Its "third country" status means home companies can no longer be involved in the way they once were. Galileo is regarded by the Union as a security programme and only firms in its 27 member states can take on sensitive work - such as payload integration.

"There may be small exceptions for certain components that come out of the UK which we can't get anywhere else. But this is what it is. This is the political reality of the day," Paul Verhoef, Esa's navigation director, told BBC News.

The agency acts as the technical and procurement agent for the EU's space projects.

UK ministers are now seeking a home-grown alternative to the ultra-precise Positioning, Navigation and Timing services offered by Galileo. There's some thought that the OneWeb satellite telecommunications network, recently acquired by the government in tandem with Indian conglomerate Bharti Global, could be involved. Quite how has yet to be spelled out, however.

All those British companies previously involved in Galileo will be hoping a concrete proposal comes forward soon so that they can transfer across all the knowledge and expertise built up over two decades.

The last Galileo payloads produced by SSTL left its Guildford factory without fanfare at the end of November. They were taken to Esa's technical centre in the Netherlands where security elements not permitted to be handled by British workers were installed.

The payloads' final destination is Bremen and the factory of OHB-System. The German company joins the payloads to the rest of the spacecraft structure, or chassis, and carries out the testing prior to launch.

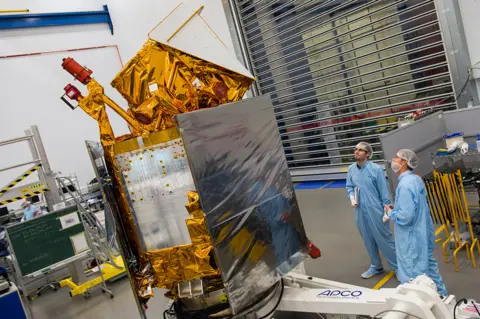

ESA

ESASSTL played a pivotal role in its more than 15-year involvement in the Galileo programme.

Not only did it assemble all 34 "full operation" payloads for the system, but it also built in rapid time the satellite that initiated Galileo.

Called Giove-A, this spacecraft, launched in 2005, was the pathfinder that secured for the European Union the use of its all-important radio frequencies.

Without those frequencies, there would be no Galileo.

SSTL representatives said they were immensely proud of what they had achieved.

Britain and the EU have agreed in principle that they should continue to cooperate on the Union's other big space project - Copernicus.

This operates a constellation of "Sentinel" satellites in orbit to monitor the Earth - everything from mapping the damage wrought by earthquakes to tracing air pollution.

London and Brussels hope to shake hands on the exact terms of the UK's involvement in the coming weeks.

It would see Britain pay a subscription of roughly €800m (£710m) over seven years, which would give it full access to Copernicus services and the ability for its companies to bid for industrial work.

Airbus DS/Max Alexander

Airbus DS/Max AlexanderAs with Galileo, Copernicus satellites are procured on behalf of the EU by Esa.

The agency's director of Earth observation (and its soon-to-be director general) Josef Aschbacher said on Thursday that continued UK involvement would be to the benefit of all.

"The UK is now negotiating with the European Commission under which conditions and how this participation looks in detail," he told BBC News.

"But this is certainly excellent from an Esa perspective because we have a very strong partner in the UK; their expertise is essential. So I'm really, really happy that the UK is hopefully joining the Brussels part of the programme."

The size of the British subscription will go a good part of the way to filling what is currently a sizeable funding gap in Copernicus.

Member states of the Union recently approved a €5.4bn budget for the programme for 2021-27, but a further €2bn-plus is still needed to fulfil all the objectives, which include launching six new satellite systems.

If the UK and other third countries, Norway and Switzerland, can be brought on board, the funding gap can be narrowed significantly.