Could the coronavirus crisis finally finish off coal?

The coronavirus crisis has changed the way we use energy, at least for now. But could the global pandemic finally finish off coal, the most polluting of all fossil fuels?

The Covid-19 crisis has been an extraordinary and terrifying time for us all, but it has been a fascinating period to cover environmental issues.

We've all enjoyed the unusually clean air and clear skies. They are the most obvious evidence that we have been living through a unique experiment in energy use.

Locking hundreds of millions of us down in our homes around the world has led to an unprecedented fall in energy demand, including for electricity.

And that has, in turn, revealed something very striking about the economics of the energy industry: the underlying vulnerability of coal, the fuel that powered the creation of the modern world.

Like a tide withdrawing, the Covid-19 crisis has exposed just how fragile the financial foundations of this dirtiest of all fossil fuels have become.

Some industry observers are even saying that coal may never recover from the coronavirus pandemic. Let's look at the evidence stacking up around the world.

Britain's electricity grid will not have burnt any coal for 60 days - as of midnight on Wednesday 10 June. That is by far the longest period since the Industrial Revolution began more than 200 years ago.

When I spoke to the National Grid, they said they weren't expecting a coal generator to be turned back on anytime soon.

In the US, more energy was consumed from renewables than from coal for the first time ever this year, despite President Donald Trump's efforts to support the industry.

By contrast, only a decade ago, almost half of US electricity came from coal.

Even in India, one of the fastest growing users of coal, demand for the fuel has fallen dramatically, helping deliver the first reduction in the country's carbon dioxide emissions for 37 years.

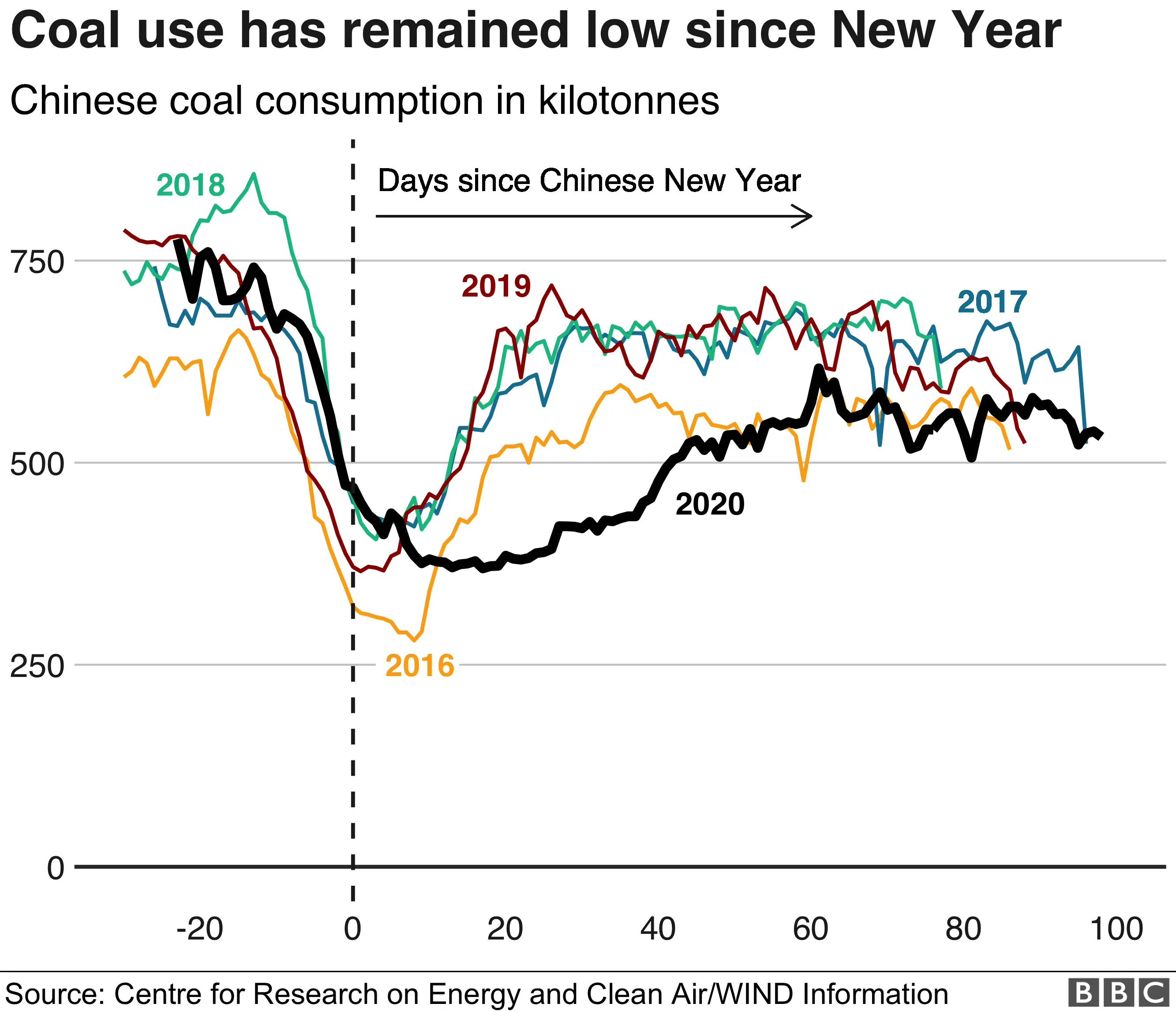

The proximate cause is the lockdown. But what has been fascinating energy economists is that coal has overwhelmingly borne the brunt of the collapse in electricity demand.

And this is a global phenomenon.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), we have seen the largest worldwide decline in coal consumption since World War Two.

Only renewables have managed to hold their ground, says Fatih Birol, the executive director of the IEA.

The trend was underway even before the coronavirus pandemic. Last year saw the largest fall in coal-powered electricity production on record worldwide.

What is striking is the shift away from the fuel isn't down to the efforts of well-meaning environmentalists - though they have played a role.

The key issue is what economists call the "marginal cost" of different sources of energy.

The idea is simple: once you've built your power stations, it is more expensive to run those that require fuel than ones that rely on wind, rain or sunshine.

Think about it. You need to keep buying coal to burn. But once you have installed your wind turbine, solar panel or hydropower plant, the electricity it produces comes pretty much free of charge.

Adding momentum is the fact that renewables are now often cheaper to build than new coal. And every year they are getting cheaper still.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis month, the Indian government put out a tender for round-the-clock electricity supply, and the price for solar with battery storage was lower than the price for power generated from coal, says energy analyst Sunil Dahiya.

If that is replicated around the world, then coal is dead.

Think of it like a ratchet.

If electricity demand rises, then in more and more countries the cheapest energy plant to build is renewables.

But if there is a sudden shortfall in electricity demand - because of a pandemic, or just because a windy day produces more electricity than expected - then it's the coal-fired power station that gets switched off.

Now imagine you are an investor considering splashing out on a new coal plant. Typically, you would expect it to operate for 30, even 40 years.

Do you really want to make that investment knowing that every passing year it is likely to spend more and more time sitting idle, at the whim of the weather forecast? Thought not.

And now add into your calculation the knowledge that the voice of the clean energy lobby is only going to grow in volume and force.

After all, coal is the biggest carbon emitter of all fuels, and it also fills our air with carcinogenic particles and toxic chemicals - none of which is currently priced into the cost of burning the stuff.

Many countries already give renewables priority access to their electricity grids. And it is not just new coal investments that look set to be squeezed out of the market.

According Mr Dahiya, the virus has revealed the fact that much of the Indian coal industry is already effectively bankrupt.

"Our coal-based power plants are operating at less than 60% of capacity", he told me. "They can't pay back the money they have been lent."

No surprise then that international investors are fleeing the sector.

In the last few weeks, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund - the world's biggest - and the French bank BNP Paribas have joined financial giants like Blackrock, Standard Chartered and JP Morgan Chase to blacklist coal investments.

What that means, says the IEA's Mr Birol, is that increasingly it will be governments that decide the future of coal.

He urges them to continue to support renewables and shun coal investments.

But here the picture is less bright.

Coal plays a big part in China's latest five-year plan, with a potential 20% increase in the size of the coal sector.

It is also helping fund coal-fired power stations in many developing countries as part of the so-called belt and road initiative.

In India, the government is finalising a multi-billion-dollar coronavirus stimulus package that will include assistance for some parts of the coal sector.

Which leaves us in a strange limbo.

Global coal consumption may well have peaked in 2019, say many analysts, but the fuel is likely to wheeze on into the 2030s.

Not an encouraging idea for anyone anxious about the world's climate.

So here is a final thought for you.

Governments don't face the same pressure to make money as companies, but they rarely want to subsidise failing industries forever - especially very polluting ones.

Follow Justin on Twitter.