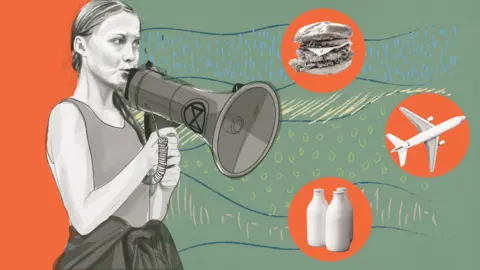

Climate change action: We can't all be Greta, but your choices have a ripple effect

BBC

BBCIs individual action pointless in the face of climate change? Let's not beat around the bush: the simple answer has to be "yes".

Think about it: what difference does one person forgoing a lamb chop for a lentil bake, deciding to catch the bus rather than take their car, or deciding not to jet off for that autumn getaway in the Balearics make if the other 7,699,999,999 of us humans here on Earth don't do anything?

It is a dispiriting conclusion and begs an obvious question, and one that I am sure has already occurred to you: why bother?

That's exactly what I asked the 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg when I met her last month. Rather than fly to her climate change meetings in New York, Greta had opted to be whisked across the Atlantic on a racing yacht.

You remember the boat, the one with the bright blue plastic poo bucket?

"The point", she told me as we bobbed in Plymouth Sound, "is to create an opinion. By stopping flying, you don't only reduce your own carbon footprint but also that sends a signal to other people around you that the climate crisis is a real thing and that helps push a political movement."

It's a good answer, and, helps explain why this Swedish teenager with pigtails has captured the world's attention.

My riposte was maybe a little rude: "So you're trying to make the rest of us feel guilty?"

"No", she replied calmly, and explained she doesn't think it is her job to tell other people how to live their lives. Rather, her convictions must guide her own behaviour.

"I don't fly because of the enormous climate impact of aviation per person."

Reuters

Reuters AFP

AFPShe acknowledges that she is a special case. "Many people listen to what I have to say and I appear a lot in media so therefore I influence a lot of people and therefore I have a bigger responsibility because I have a bigger platform."

Previously, she's tried attending conferences by video link but it just doesn't make as much of an impression. "I think it will have a bigger impact if I and many other young people are actually there".

And judging by the publicity she's getting, she is right.

But let's be honest, you're no Greta Thunberg. Even if your choices do ripple out into the world and affect a few other people, your decision to eat a little less meat and turn down the thermostat a notch isn't the clarion call that is about to rally the world to the carbon cutting cause, is it?

So, why should individuals take action?

That is a question for a philosopher. It's their job to wrestle with debates about what principles should guide our behaviour. And I've got just the man. Prof Peter Singer of Princeton University in the US has been described as "the world's most influential living philosopher" by New Yorker magazine.

For more on the UK's efforts to tackle CO2 emissions, download the BBC Briefing on energy. Part of a mini-series of downloadable guides to the big issues in the news, it has input from academics, researchers and journalists and is the BBC's response to demands for better explanation of the facts behind the headlines.

Prof Singer describes himself as an expert in practical ethics and he is very clear on this question. He doesn't just think we should all take action but argues there is a very strong moral obligation why we must do so.

"I think this is one of the great moral challenges of the 21st Century, perhaps the greatest moral challenge", he says. "If we are not acting, we are endangering everyone who is alive now and also future generations."

He compares you failing to cut your emissions with you taking a bulldozer and razing the crops of a subsistence farmer in Africa. If you did that, everyone would agree it was wrong, but the greenhouse gases you are responsible for have the same result, he argues.

The fact that the cause is invisible gases, and that the effect may be felt in the distant future, doesn't allow each and every one of us to escape the moral obligation to act, Prof Singer insists.

The reason is that our right to freedom of action doesn't extend to harming others.

Here's another metaphor. Imagine there's a speed limit on a busy shopping street and someone says, "I'm going to drive down there with my pedal to the metal, but don't worry, there's a good chance I won't kill anyone."

You wouldn't say that's fine, maintains Prof Singer. "You'd say no, you don't have any freedom or right to put other people in grave danger of being injured or killed. And that is exactly what we are doing by going ahead with the levels of greenhouse gas emissions we are emitting today."

He says the fact that each of us only plays a minuscule part in the process doesn't make a jot of difference: the obligation on us all to act remains.

I bet most of us instinctively recognise that there is real force in these arguments. So, why aren't all of us doing more to cut our emissions already?

Time for the insights of a behavioural psychologist. Step up Professor Kelly Fielding of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia.

We are not the free-thinking independent spirits we imagine ourselves to be, says Prof Fielding.

"What we know as social psychologists is that people are very influenced by what others do, even though we don't think we are", she explains. "It's a paradox. We think we make our own decisions, but the truth is we look to others for guidance about how we should behave."

When it comes to climate change, the problem is that we just aren't getting the cues we need from our friends and families or, for that matter, from government and business, she says.

Yet surveys show that people all over the world are increasingly worried about climate change.

A US poll published in June illustrated the point very forcefully. The Reuters survey found that while 69% of Americans wanted the government to take "aggressive" action to combat climate change, only a third would be willing to pay an extra $100 to make it happen.

What the respondents are saying is: "Yes, there's a problem, but it's not my job to sort it."

But don't despair, says Professor Fielding. The work of behavioural psychologists suggests It should be possible to flip these findings on their head.

If people need cues from others before they change their behaviour, then all we need to do is get some people to start taking action and others will follow, she argues.

Which brings us full circle; all the way back to Greta Thunberg and that super-fast carbon-fibre yacht.

As Greta says, our actions are important not because they have a material effect on climate change, but because of the message they send to others.

What you do influences your friends and family and will help create the political space for governments and businesses to take action. That, in turn, is likely to encourage other people and other countries to do more.

And it is happening already. Who would have thought that a company making meat-free burgers could be worth almost $4bn; that the world's most powerful oil cartel would brand climate striking students the "greatest threat" to the oil industry; or that climate change would become the key issue for US Democratic presidential candidates?

Yes, what I am suggesting is the possibility of a virtuous circle. And yes, this is an argument for us all to be a lot more optimistic about what can be achieved.

Because there's another crucial point to remember. Climate change isn't binary: it doesn't just happen or not happen. The crucial question for us all is how much climate change the world will experience.

We've already seen a degree of warming. The UN has urged us to try to stay below 1.5 degrees.

So here's the thing: the more action we all take, the less our climate will change and the more liveable the world will be for ourselves, our progeny and all the rest of the magnificent abundance that is life on earth.

Now come on, that's worth making a few lifestyle changes for, isn't it?