Five things we've learned from nature crisis study

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe most comprehensive and detailed review of the state of nature has been published in Paris. Our environment correspondent Matt McGrath extracts the key messages.

1 - "Boy, we are in trouble"

This phrase was uttered by Prof Sir Bob Watson who has chaired this report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

While Sir Bob went on to explain that there is still hope and much we can do to save nature, I think it's worth dwelling for a moment on just how much trouble we are in.

Globally, two billion people rely on wood to meet their primary energy needs. Around 70% of cancer drugs are natural, or are synthetic products inspired by nature.

Then there's all that water that nature cleans, all the food it provides, all the CO2 it absorbs, all the storms that it blocks.

I could go on, but the picture is very plain.

Humans are more dependent on nature now than at any time in our history.

Over the past 50 years, as the world's population has doubled, we have pulled more people out of poverty than ever before.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd how have we done it?

By burning, poisoning and trashing large sections of the most biodiversity-rich lands and oceans.

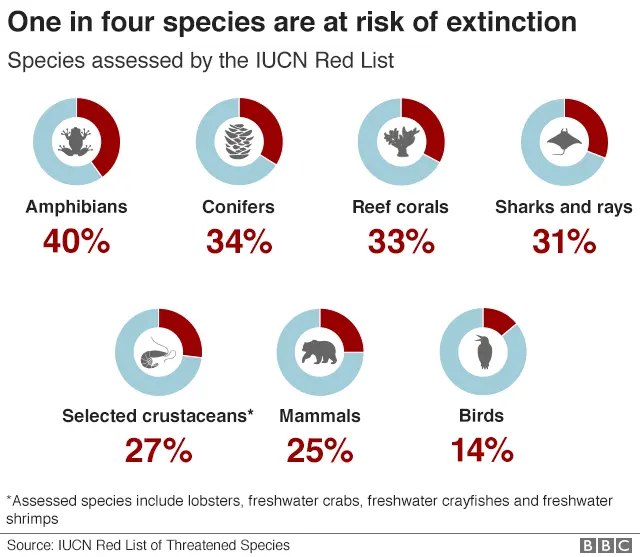

This has killed off thousands of species and now threatens a million more.

"Nature is changing in part because there's more of us and we are consuming more," said one of the IPBES co-ordinating lead authors, Dr Kate Brauman.

"As people become more affluent they have bigger footprints, they eat more they drive more and they fly more."

2 - "We need to change the stories in our heads…"

One key message from the assessment is that we need to re-evaluate what we mean by the idea of a "good life".

For centuries, in western culture, this has all been about accumulating wealth, working hard, making sacrifices for the benefits of our children.

Progress, as defined in many families, has meant children earning more than their parents. More money, more things.

"We need to change the way we think about what a good life is, we need to change the social narrative that puts an emphasis on a good life depending on a high consumption and quick disposal," said Prof Sandra Diaz, one of the co-chairs of the IPBES report.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We need to shift it to an idea of a fulfilling life that is more aligned with a good relationship with nature, and a good relationship with other people, with the public good.

"We need to change the stories in our heads, because they are the ones that are now enacted in decisions all the way from the individual up to government."

She added: "Changing that is not easy but this is what it would take to reach the better future for the children that are born this year."

3 - The value of nature or the nature of value?

One of the major themes of this assessment is the term "nature's contribution to people".

This is a central concept that the authors really want to drive home.

While it looks like a bland bit of bureaucratese, it actually carries a lot of weight.

For a long time economists have tried to encourage the idea that the value of nature was best expressed in monetary terms.

They have argued that this makes it easier to explain to politicians and citizens that wetlands or pollinators matter because they have value and contribute to the economy in a real financial sense.

The phrase they have used to capture this sense of the value of nature is "ecosystems services".

But some ecologists argue that a financial definition is very damaging for nature, allowing it to be commodified and treated as just another good.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis new assessment wants the world to move on from measuring nature's value in pounds, dollars or yen. It wants to ensure that the full value of natural resources are taken into account.

"If you have a natural forest it doesn't appear at all in your account books at national level, your wealth is not affected at all," said Ina Porras, from the International Institute for Environment and Development.

"The moment you allow the extraction of timber then your GDP will increase - it's only by allowing the destruction of this resource that the economy seems to be growing."

"What we need to do is change that because that forest is providing many other services that are simply not accounted, if you destroy it, looks as if you are increasing your wealth but you are not."

4 - Local is good for global…

One of the key differences in this report is that the authors have worked hard to include a broader range of knowledge than in many typically "western" scientific studies.

They have sought out indigenous and local knowledge and given it due weight in the report.

One key finding is that while nature is declining in lands managed by local communities, it is declining less rapidly than in other areas.

The authors say that local knowledge and understanding on how to manage nature should be given more weight by governments. We can all learn from them.

The Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, has seen evidence of this power of local knowledge in action.

After the NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) treaty was signed in 1994, there were expectations that hybrid varieties of maize from the US would swamp local, native breeds.

"The farmers there tell me that the locally adapted traditional varieties of maize do better under climate change with increasing droughts," says Dr Rinku Roy Chowdhury, from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who has worked in the region.

"But they are not sure, so they are hedging their bets and investing in several different varieties.

"It is a really interesting process of decision-making under uncertainty which is we are all trying to do as scientists focused on global change. It is humbling and illuminating to see that we have different types of scientists in these local farmers, thinking and dealing with climate change."

5 - 12 months to save the Earth? Not quite...

One key takeaway from this report is that political efforts to enshrine protection of nature have fallen desperately flat.

Back in 2010, at a meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity in Aichi, Japan, delegates set themselves a series of targets for conservation for 2020.

According to the new assessment, good progress has only been made on four of the 20 goals.

The negative trends in species loss will also make the Sustainable Development Goals - the UN blueprint for addressing global challenges such as poverty, environmental degradation and peace - harder to achieve.

This will have real consequences for real people as they experience hunger, health issues, water scarcity and poverty in general.

So is there any political progress on the horizon?

Well, just as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) informed the Paris agreement on global warming in 2015, this IPBES report will inform the talks on a "new deal for nature and people".

This is due to be negotiated at a key meeting in China next year.

If a new global deal on nature is to be struck, then it will probably need the participation of heads of state.

Right now, despite the evidence from the IPBES report, that seems a very big ask.

Follow Matt on Twitter.