Sustainable students: Recycling clothes for London Fashion Week

BBC

BBCAfter a damning report from MPs on the clothing industry's environmental credentials, how can we make our wardrobe more sustainable? Two students took up the challenge of repairing, reusing and recycling clothes for a London Fashion Week show.

It's mid-afternoon, and Loughborough University student Marcus Rudd is going through his wardrobe, piece by piece.

He is with sustainable stylist Alice Wilby, and it turns out his wardrobe is not as environmentally-friendly as he had hoped - as he announces he buys around 10 to 15 T-shirts a year.

"Did you know it takes about 3,000 litres of water to make one cotton T-shirt?" Alice asks him, bursting his bubble.

"That's about as much water as [the average person's] drinks in three years."

And then they come to the high-priced fashion in his wardrobe - the Versace jeans and Giorgio Armani jacket.

Alice is quick to point out the styling is similar to that of many sustainable brands.

"There isn't anything to me specifically that sets them aside as being designer - it's a pretty classic cut, it's a pretty classic style," she says.

"I feel like you could buy this from a vintage shop," she adds, of one of Marcus's coats in which he takes extra pride.

The fashion industry is a major contributor to greenhouse gases, water pollution, air pollution and the over-use of water.

It's exacerbated, MPs say, by so-called "fast fashion" - inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers.

The sector is proving increasingly popular.

Goby Chan, a fellow Loughborough University student flat-sharing with Marcus, says the low price makes such clothes a particularly appealing prospect for young people.

"You just go for it," she says, precisely because it's so cheap.

But it also means many people purchase clothes they never wear - buying clothes in the hope of one day wearing them on a night out due to the fear others will notice you've worn the same dress twice.

The scale of the problem is brought to life with a visit to the Oxfam recycling centre in Batley, Yorkshire.

They sort through 80 tonnes of donated clothing and textiles per week.

In one of their huge barns are stacks upon stacks of clothes, formed in to bales each weighing half a tonne.

The British public sends the equivalent of 11,000 such bales to landfill each week, a figure that visibly shocks Gobi and Marcus.

Of course, the clothing bales at the Oxfam factory do not go to landfill - they will instead be put to other purposes, such as insulation.

This is because about 6% of the clothing Oxfam receives from donations are not of a fit state to be worn again - a problem increasing with fast fashion.

"We do get a lot of that low-quality, High Street clothing in, and there's just nothing we can really do with it," explains Oxfam's Holly Bentley.

So how can we, as consumers, turn the tide?

For Alice, it is about the three 'R's - recycle, repair and reuse.

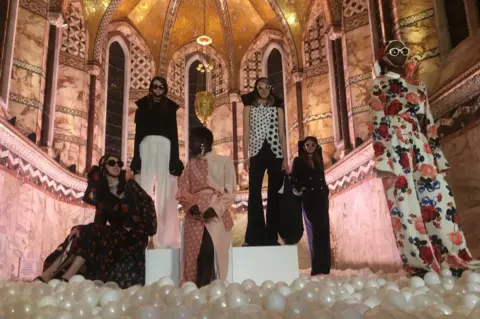

She sets Goby and Marcus a challenge - to create an outfit to wear in a sustainable fashion show at London Fashion Week - using only second-hand and reused clothing, plus a repaired or restyled item from their wardrobe.

The show is run by Amy Powney, creative director of sustainable designer brand Mother of Pearl.

She explains that ethical fashion is not just about the fabric a garment is made out of, but the whole supply chain.

"The average they say [your clothes travel during production] is five countries, for every garment you buy," she explains, much to Gobi and Marcus's surprise.

"For each stage you have to send it to another country - package it off each time, then ship it - which is fuel and energy.

"We'd love to see legislation for the labels in your garment not just to say 'Made in' wherever it's from - but 'grown in', 'finished in', 'manufactured in', so you can understand there is a longer process."

Goby thinks this would be a good step forward.

"I think people would actually treasure the clothing more when they actually know there are so many processes in one jumper," she says.

"They will think twice before they actually buy so many of them."

It is with this sustainably-charged mindset that both enter their task.

Marcus chooses to repair a traditional Indian Kurta given to him by his grandmother, pairing it with some dark blue jeans and brown shoes that he bought from a charity shop.

Goby picks a black top with sheer detail sleeves to repair, with a black chiffon detail dress from a local charity shop.

When the big day comes a few days later, they are ready to model the ethical outfits waist-deep in a pit of balls made from recycled plastic.

Each one is intended to represent the millions of microfibres that wash off our clothes when they get washed, entering the UK's water streams and eventually the food chain.

For Goby, it is the culmination of a "very exciting" experience, but also one that has opened her eyes to the damage the fashion industry is causing.

Now before buying clothes, she says, she will think about what material it is made from, and be more aware of what website she is buying from.

"I do think it is a really good option to be buy less, but buy better," she adds.

She also promises to rewear clothes that have become lost in her wardrobe, and refashion others into new and unique accessories.

As for Marcus, he has already bought more clothes from vintage shops - a trend he very much plans to continue.