Does Jurassic Park make scientific sense?

Universal/Tippett Studio

Universal/Tippett StudioIn 1993, Steven Spielberg's film Jurassic Park defined dinosaurs for an entire generation.

It has been credited with inspiring a new era of palaeontology research.

But how much science was built into Jurassic Park, and do we now know more about its dinosaurs?

As its 25th anniversary approaches, visual effects specialist Phil Tippett and palaeontologist Steve Brusatte look back at the making of the film, and what we've learned since.

So, first of all, what did Jurassic Park get wrong? It started off by inheriting some complications from Michael Crichton's novel, on which the film was based.

"I guess Cretaceous Park never had that same ring to it," laughs Brusatte.

"Most of the dinosaurs are Cretaceous in age, that's true."

The Cretaceous period, which followed on from the Jurassic, was home to many of the dinosaurs which feature heavily in the film, including Tyrannosaurus rex, Velociraptor and Triceratops.

Universal/Tippett Studio

Universal/Tippett StudioThe idea of recreating dinosaurs from preserved DNA also proves problematic.

"In order to clone a dinosaur you would need the whole genome, and nobody's ever even found a little bit of dinosaur DNA," says Brusatte. "So we're talking about something that's pretty difficult, if not impossible."

Quibbling about such details may seem inconsequential. But for a film that proudly treats its prehistoric cast of creatures as characters rather than monsters, Jurassic Park treads a fine line between scientific accuracy and cinematic fantasy.

How to build a dinosaur

Case in point - building an animal that no human being has ever seen, and making it as realistic as possible.

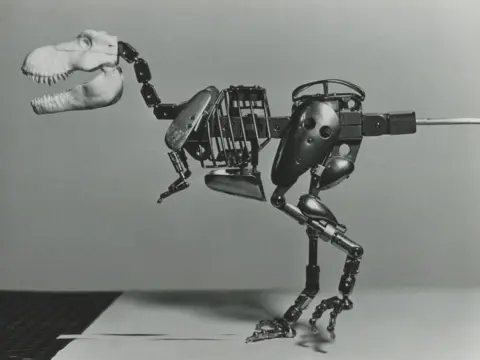

At the time, Jurassic Park was groundbreaking in its use of computer animation in tandem with animatronics.

Stop motion expert Phil Tippett, who had previously worked on Star Wars, was brought in as dinosaur supervisor, a role which would later earn him fame as an internet meme.

Tippett Studio

Tippett StudioIn addition to the film's consulting palaeontologist Jack Horner, Tippett also had a great deal of dinosaur knowledge. "[I] bought every book that came out on dinosaurs. So I was pretty well in tune with what the state of the science was at that point in time," he told the BBC.

T. rex

Tippett remembers having to rein in some of the descriptions from the novel.

"Crichton would have a Tyrannosaurus pick up the jeep like Godzilla. I was like a reality check to say 'well no he wouldn't do that, because... the physics don't work.'"

Tippett Studio

Tippett Studio"It still is a pretty good portrayal really," says Brusatte. "I think that was by far the most accurate depiction of T. rex that had ever been done up until that time."

"We now know that T. rex had really good vision, so if you sit still it could see you. You wouldn't be able to hide from it. It's also got a great sense of smell and a great sense of hearing, and all that's really emerged from the CAT scans of its brain, which have all taken place after the year 2000," he explains.

Computer modelling has also shown that T. rex probably couldn't notch up a speed much above 20km per hour. That's still faster than humans, but tyrannosaurs were likely unused to chasing prey over long distances. So running away was still worth a shot...

Tippett Studio

Tippett StudioRaptors

Translating fossilised remains into the movements of a living creature is difficult work, so Tippett's team also went out to observe animals that resembled the dinosaurs they were creating. They watched elephants to understand the gigantic, long necked brachiosaur, and ostriches for the stampeding Gallimimus.

Velociraptors, however, would have looked decidedly different to those in the film.

"The real Velociraptors from Mongolia are just about the size of a poodle. And not one of those big weird looking poodles, but a miniature poodle," explains Brusatte.

"They were kind of a generic version of a thing called Deinonychus," says Tippett, "which was much smaller than the raptors were in the movie."

We now know Deinonychus, meaning terrible claw, to be a somewhat intimidating, feathered early ancestor of modern day birds.

With the first feathered dinosaurs found in the late 1990s, and a feathered relative of T. rex uncovered in 2004, our visual understanding of dinosaurs has radically changed since 1993.

Emily Willoughby

Emily WilloughbyYet in 2015, Jurassic World came under fire for sticking to the featherless designs established in Jurassic Park over two decades earlier.

It's one thing that Brusatte finds really jarring.

"We now know that dinosaurs, maybe even all dinosaurs, had some type of feather... It's a little bit weird actually for me to see dinosaurs portrayed without feathers. It just doesn't seem natural," he told the BBC.

Jurassic Park in 2018

"I have completely different ideas of what [dinosaurs] should be like now," says Tippett. "If we were making a different dinosaur movie that didn't have to be Jurassic Park, I would do things totally differently…. a lot of this stuff that they've discovered about feathers is pretty significant and there's a lot of really interesting things you could do."

Brusatte is all in favour: "A T. rex is like a bus-sized Big Bird from hell, I think that's much scarier than a scaly green T. rex."

Emily Willoughby

Emily WilloughbyYet looking back at Jurassic Park, Brusatte finds little to dislike.

"I think on balance Jurassic Park has been such a positive for palaeontology. Of course I could nitpick about the little inaccuracies but I think those are outweighed probably a million fold by the good that the movie has done.

"I don't know if I would have a job now if Jurassic Park didn't exist."

Follow Mary on Twitter.

Illustrations courtesy of Emily Willoughby

Jurassic Park previs sequence courtesy of Tippett Studio