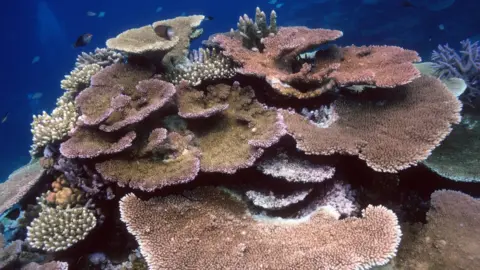

Heatwaves 'cook' Great Barrier Reef corals

Coral CoE/Gergely Torda

Coral CoE/Gergely TordaProlonged ocean warming events, known as marine heatwaves, take a significant toll on the complex ecosystem of the Great Barrier Reef.

This is according to a new study on the impacts of the 2016 marine heatwave, published in Nature.

In surveying the 3,863 individual reefs that make up the system off Australia's north-east coast, scientists found that 29% of communities were affected.

In some cases up to 90% of coral died, in a process known as bleaching.

This occurs when the stress of elevated temperatures causes a breakdown of the coral's symbiotic relationship with its algae, which provide the coral with energy to survive, and give the reef its distinctive colours.

Certain coral species are more susceptible to this heat-induced stress, and the 2016 marine heatwave saw the death of many tabular and staghorn corals, which are a key part of the reef's structure.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryResearchers led by Terry Hughes at Australia's ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies looked at aerial observations of the entire 2,300km reef between March and November 2016. These were combined with underwater surveys at over 100 locations.

"We saw some corals rapidly dying," explained Dr Scott Heron, another of the study's authors.

"Bleaching... is essentially a starvation process that occurs over one to two months. This rapid onset is not the same starvation mechanism. The best way to describe it is akin to cooking," added the Noaa Coral Reef Watch scientist.

They found that these "cooked" corals were dying within two to three weeks.

The northern section of the reef, some 700km long, was worst affected, with 50% of the coral cover in the reef's shallowest areas being lost within eight months.

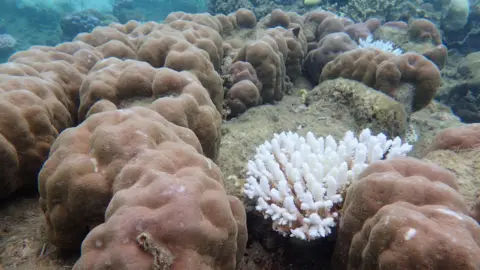

Coral CoE/Gergely Torda

Coral CoE/Gergely TordaHealing time

Not all areas of the reef, or all coral species, were equally affected.

Some were better able to tolerate the stressful conditions, or to bounce back afterwards.

"There have been some signs of recovery," said Dr Heron.

But in other areas the team noted that stressed coral populations were more susceptible to disease, and have since seen outbreaks.

In many areas of the reef, there was a reduction in the diversity of coral species: shifting from the dominance of fast-growing species like tabular coral to simpler, slower growing varieties.

In the much warmer waters of the Red Sea, researchers at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia have been looking at how corals can potentially adapt to increased temperatures.

Their results, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, indicate that it is the partner algae, and not the coral themselves, who may be responsible for a capacity to tolerate heat stress.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith year-round temperatures of 29 - 30C, the Red Sea is a more thermally stable environment than many other reef communities.

The Symbiodinium algae there have adapted to tolerate the warmest ocean waters in the world, and it appears this may also make them more resilient to the stresses of changing temperatures.

Partnering up with these particular algae could give corals an advantage.

It's not yet clear what this could mean for other reef environments in danger of bleaching, but lead author Maha Cziesielski says that swapping to a different algae species is something corals already do in nature: "It's quite common... it's called symbiont shuffling. Association with more 'thermotolerant' algae can play a very important role in adapting to warmer environments," she told BBC News.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe cautions that there will be no silver bullet when it comes to stalling the impact of climate change on reef environments. "We don't understand the reef system well enough yet to have one answer... I don't think we have a large scale solution for this yet. [But this is] work that can in the future lead to something bigger."

For Dr Heron, the increasing frequency of marine heatwaves on the Great Barrier Reef is a pressing issue.

2016 was part of the third, and longest, mass coral bleaching event so far recorded.

"We're very concerned that the return period between events is now much shorter than the recovery time required," he told BBC News.

"If we continue on the trajectory we're going, [the reef] will not be the same ecosystem it has been.

"Will there be a reef? Yes. Will it be the same Great Barrier Reef we have known historically? No."

Coral CoE/Mia Hoogenboom

Coral CoE/Mia HoogenboomProf Jörg Wiedenmann from the University of Southampton's Coral Reef Laboratory agrees that, if present conditions continue, significant change lies ahead.

"Looking into the future of the Great Barrier Reef and reefs elsewhere, corals in the Arabian Gulf and other extreme temperature environments send both signs of hope and dire warning: reef communities can shift to states that tolerate more heat stress, however, this will likely come at the price of a loss of about 90% of coral species," he explained.

"Therefore," he added, "efforts to protect these key ecosystems need to be made at all levels."