Stephen Hawking: The book that made him a star

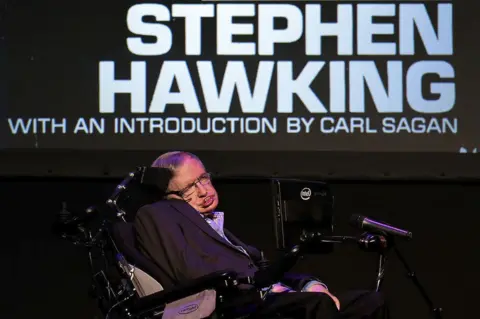

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStephen Hawking was the most remarkable author I had the privilege of working with during my career as the director of science publishing at Cambridge University Press.

In 1982, I had responsibility for his third academic book for the Press, Superspace And Supergravity.

This was a messy collection of papers from a technical workshop on how to devise a new theory of gravity.

While that book was in production, I suggested he try something easier: a popular book about the nature of the Universe, suitable for the general market.

Stephen mulled over my suggestion.

He already had an international reputation as a brilliant theoretical physicist working on rotating black holes and theories of gravity.

And he had concerns about financial matters: importantly, it was impossible for him to obtain any form of life insurance to protect his family in the event of his death or becoming total dependent on nursing care.

So, he took precious time out from his research to prepare the rough draft of a book.

At the time, several bestselling physics authors had already published non-technical books on the early Universe and black holes.

Stephen decided to write a more personal approach, by explaining his own research in cosmology and quantum theory.

As he himself pointed out it, his area of interest had "become so technical that only a very small number of specialists could master the mathematics" used to describe it.

For a starting point, he took some themes from a course of advanced lectures that he had recently given at Harvard University.

These had catchy titles such as "The edge of spacetime", "Black holes and thermodynamics", and "Quantum gravity".

In the 1980s, my office and Stephen's were in the same courtyard in central Cambridge, so I often chatted with him about publishing.

One afternoon he invited me to take a look at the first draft, but first he wanted to discuss cash.

He told me he had spent considerable time away from his research, and that he expected advances and royalties to be large.

When I pressed him on the market that he foresaw, he insisted that it had to be on sale, up front, at all airport bookshops in the UK and the US.

I told him that was a tough call for a university press.

Then I thumbed the typescript. To my dismay, the text was far too technical for a general reader.

A few weeks later he showed me a revision, much improved, but still littered with equations.

I said: "Steve, it's still too technical - every equation will halve the market."

He eventually removed all except one, E = mc². And he decided, fortunately, to place it with a mass market publisher rather than a university press.

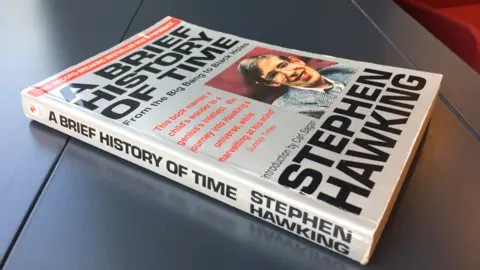

Bantam published A Brief History of Time in March 1988.

Sales took off like a rocket, and it ranked as a bestseller for at least five years.

Total sales approached 10 million copies.

The book's impact on the popularisation of science has been incalculable.

Stephen was an inspirational ambassador for the power of science to provide rational accounts of the physical laws governing the natural world.

Dr Simon Mitton is a historian of science at the University of Cambridge