A mission to the Pacific plastic patch

A mariner who has spent years travelling "hundreds of thousands of nautical miles" to measure the impact of plastic waste in the ocean has estimated that a "raft" of plastic debris spanning more than 965,000 square miles (2.5m sq km) is concentrated in a region of the South Pacific.

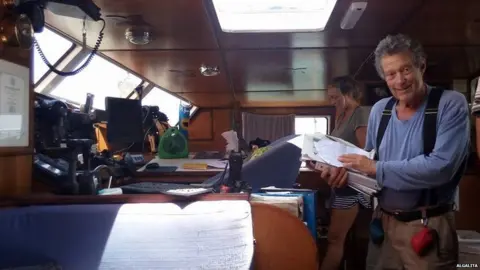

Capt Charles Moore has just returned from a sampling expedition around Easter Island and Robinson Crusoe Island.

He was part of the team which discovered the first ocean "garbage patch" in the North Pacific gyre in 1997 and has now turned his attention to the South Pacific.

Although plastic is known to occur in the Southern Hemisphere gyres, very few scientists have visited the region to collect samples.

Oceanographer Dr Erik van Sebille, from Utrecht University, says the work of Capt Moore and his colleagues will help fill "a massive knowledge gap" in our understanding of ocean plastics.

"Any data we can get our hands on is good data at this point," he told BBC News.

Capt Moore explained that the space occupied by sub-tropical gyres - areas of the ocean surrounded by circulating ocean currents - is approximately the same size as the entire land mass of the Earth, but they are now being "populated by our trash".

The phenomenon of oceanic garbage patches was originally documented in the North Pacific, but plastic has now been found in the South Pacific, Arctic and Mediterranean.

"It's hard not to find plastic in the ocean any more," Dr van Sebille said. "That's quite shocking".

Algalita

AlgalitaCapt Moore is the founder of Algalita Marine Research, a non-profit organisation aiming to combat the "plastic plague" of garbage floating in the world's oceans.

For more than 30 years, he has transported scientists to the centre of remote debris patches aboard his research ship, Alguita.

Dragging nets behind the vessel, the crew sieves particles of plastic from the ocean, which are then counted and fed into estimates of global microplastic distribution.

Although scientists agree that plastic pollution is a widespread problem, the exact distribution of these rafts of ocean garbage is still unclear.

"If we don't understand where the plastic is, then we don't really understand what harm it does and we can't really work on solving the problem," said Dr van Sebille.

Eating rubbish

Capt Moore and his crew hope to address this lack of data through their research trips.

On this latest voyage, Capt Moore and his colleagues are also investigating how plastic in the South Pacific Ocean may be threatening the survival of fish.

Lanternfish, that live in the deep ocean, are an important part of the diet of whales, squid and king penguins and the Algalita team says that plastic ingestion by lanternfish could have a domino effect on the rest of the food chain.

Christiana Boerger, a marine biologist in the US Navy, who has worked with the organisation, told BBC News that the problem of plastic consumption in fish can be "out of sight, out of mind".

Algalita

AlgalitaShe explained that "scientists need to actually travel to these accumulation zones" in order to bring the issue to the world's attention.

Ms Boerger has seen the impact of oceanic garbage patches first hand, aboard the Alugita and she says that some fish species "have more man-made plastic in their stomach than their natural food".

Globally, most of the plastic that ends up in the oceans comes from the land.

Litter is typically transported offshore by currents, which then form large revolving bodies of water, or gyres.

But Capt Moore says the South Pacific garbage patch is different from those in the Northern Hemisphere, because most of the litter appears to have come from the fishing industry.

Elsewhere, scientists are shifting their attention away from remote mid-ocean garbage patches to locations closer to home.

"If you think about plastic in terms of its impact, where does it harm marine life?" Dr van Sebille posed.

"Near coastlines is where biology suffers. It's also where the economy suffers the most."

Dr van Sebille also says that future research efforts need to focus on ecologically sensitive regions along the continental shelf. Even though the garbage patches cover a very large area "they are not that ecologically important", he said.

SPL

SPLHis team has previously studied the risk of plastics to marine animals, including turtles and sea birds. "Every time, we found that the risk is mostly outside of the garbage patches," he warned.

In the future, Dr van Sebille hopes to understand more about how plastic ends up on the coastline and is then subsequently transported to the oceans by storms. Interrupting this process might be an important mechanism for halting the growth of ocean garbage patches.

"A beach clean-up might turn out to be a very efficient way of cleaning up the ocean," he suggests.

In the meantime, humanity's love affair with plastic is unlikely to end soon. Plastic "will never be the enemy", concedes Capt Moore, "It has too many uses".

He explained that plastic pollution travels across national borders, so dealing with it required international collaboration.