China's quantum satellite in big leap

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe term "spy satellite" has taken on a new meaning with the successful test of a novel Chinese spacecraft.

The mission can provide unbreakable secret communications channels, in principle, using the laws of quantum science.

Called Micius, the satellite is the first of its kind and was launched from the Gobi desert last August.

It is all part of a push towards a new kind of internet that would be far more secure than the one we use now.

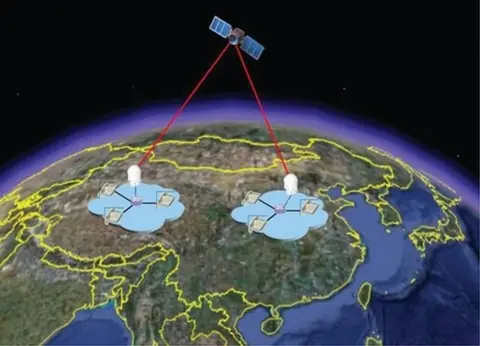

The experimental Micius, with its delicate optical equipment, continues to circle the Earth, transmitting to two mountain-top Earth bases separated by 1,200km.

The optics onboard are paramount. They're needed to distribute to the ground stations the particles, or photons, of light that can encode the "keys" to secret messages.

"I think we have started a worldwide quantum space race," says lead researcher Jian-Wei Pan, who is based in Hefei in China's Anhui Province.

'Messy business'

Quantum privacy in many ways should be like the encryption that already keeps our financial data private online.

Before sensitive information is shared between shopper and online shop, the two exchange a complicated number that is then used to scramble the subsequent characters. It also hides the key that will allow the shop to unscramble the text securely.

The weakness is that the number itself can be intercepted, and with enough computing power, cracked.

Quantum cryptography, as it is called, goes one step further, by using the power of quantum science to hide the key.

As one of the founders of quantum mechanics Werner Heisenberg realised over 90 years ago, any measurement or detection of a quantum system, such as an atom or photon of light, uncontrollably and unpredictably changes the system.

This quantum uncertainty is the property that allows those engaged in secret communications to know if they are being spied on: the eavesdropper's efforts would mess up the connection.

NSSC

NSSCThe idea has been developed since it was first understood in the 1980s.

Typically, pairs of photons created or born simultaneously like quantum twins will share their quantum properties no matter how long they are separated or how far they have travelled. Reading the photons later, by shopper and shop, leads to the numerical key that can then be used to encrypt a message. Unless the measurements show interference from an eavesdropper.

A network established in Vienna in 2008 successfully used telecommunications fibre optics criss-crossing the city to carry these "entangled photons", as they are called. But even the clearest of optical fibres looks foggy to light, if it's long enough. And an ambitious 2,000km link from Beijing to Shanghai launched last year needs repeater hubs every 100km or so - weak points for quantum hackers of the future to target.

And that, explains Anton Zeilinger, one of the pioneers of the field and creator of the Vienna network, is the reason to communicate via satellite instead.

"On the ground, through the air, through glass fibres - you cannot go much further than 200km. So a satellite in outer space is the choice if you want to go a really large distance," he said.

The point being that in the vacuum of space, there are no atoms, or at least hardly any, to mess up the quantum signal.

That is what makes the tests with Micius, named after an ancient Chinese philosopher, so significant. They have proved a spaced-based network is possible, as revealed in the latest edition of the journal Science.

Technical tour de force

Not that it is easy. The satellite passes 500km over China for just less than five minutes each day - or rather each night, as bright sunlight would easily swamp the quantum signal. Micius' intricate optics create the all-important photon pairs and fires them down towards telescopes on some of China's high mountains.

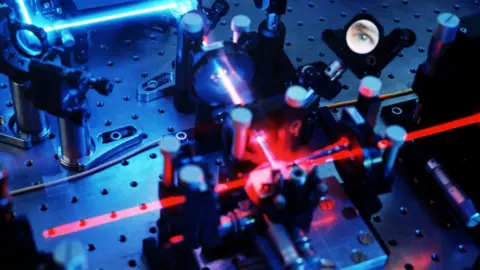

"When I had the idea of doing this in 2003, many people thought it was a crazy idea," Jian-Wei Pan told the BBC World Service from his office in the University of Science and Technology of China. "Because it was very challenging already doing the sophisticated quantum optics experiments in a lab - so how can you do a similar experiment at a thousand-kilometre distance and with optical elements moving at a speed of 8km/s?"

Additional lasers steered the satellite's optics as it flew over China, keeping them pointed at the base stations. Nevertheless, owing to clouds, dust and atmospheric turbulence, most of the photons created on the satellite failed to reach their target: only one pair of the 10 million photon pairs generated each second actually completed the trip successfully.

But that was enough to complete the test successfully. It showed that the photons that did arrive preserved the quantum properties needed for quantum crypto-circuits.

"The Chinese experiment is a quite remarkable technological achievement," enthused mathematician Artur Ekert in an e-mail to the BBC. It was as a student in quantum information at Oxford University in the 1990s that Ekert proposed the paired-photon approach to cryptography. Relishing the pun, he added wryly "when I proposed the scheme, I did not expect it to be elevated to such heights."

Alex Ling from the National University of Singapore is a rival physicist. His first quantum minisatellite blew up shortly after launch in 2014, but he is generous in his praise of the Micius mission: "The experiment is definitely a technical tour de force.

"We are pretty excited about this development, and hope it heralds a new era in quantum communications capability."

SPL

SPLThe next step will be a collaboration between Jian-Wei Pan and his former PhD supervisor, Anton Zeilinger in the University of Vienna - to prove what can be done across a single nation can also be achieved between whole continents, still using Micius.

"The idea is the satellite flies over China, establishes a secret key with a ground station; then it flies over Austria, it establishes another secret key with that ground station. Then the keys are combined to establish a key between say Vienna and Beijing," he told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

Pan says his team will soon arrive in Vienna to start those tests.

Meanwhile, Zeilinger is working on Qapital, a quantum network connecting many of the capitals of Europe, Vienna and Bratislava. Existing optic fibres laid alongside data networks but not currently used could make the backbone of this network, Zeilinger believes.

"A future quantum internet," he says, "will consist of fibre optic networks on the ground that will be connected to other fibre networks by satellites overhead. I think it will happen."

Pan is already planning the details of the satellite constellation that will make this possible.

The need? Secrecy is the stuff of spy agencies, who have large budgets. But financial institutions which trade billions of dollars internationally day by day also have valuable resources to protect.

Although some observers are sceptical they would want to pay for a quantum internet, Pan, Zeilinger and the other technologists think the case will be irresistible once one exists.