Afghanistan: The 'pure devastation and guilt' of British-Afghans

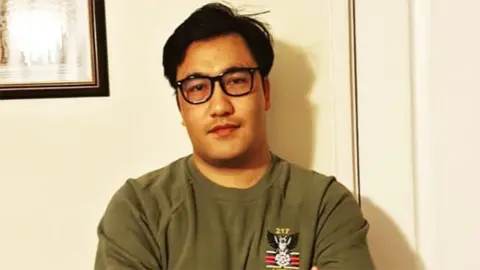

Parwiz Karimi

Parwiz KarimiThe Taliban takeover of Afghanistan may be happening more than 3,600 miles away from the UK, but it feels much closer to home for British-Afghans.

Before coming to the UK as an asylum seeker, 24-year-old Parwiz Karimi was born and grew up in Afghanistan.

His childhood memories include being confronted by Taliban members who would cross into his village with their weapons, with his grandmother telling him and his siblings to "run to the mountains" to find safety.

As he tries to keep track of the fast-moving situation in his home country, Parwiz is feeling guilty and worried about his many family members who still live there.

"I'm here sitting in my house peacefully studying. And they're struggling to find food," he tells Radio 1 Newsbeat.

"There is so much I can do here but at the same time, there's nothing I can do for them."

Parwiz has been able to speak to some of his uncles, but has been cut off from family in areas where "network communication is a luxury".

'If I stayed I'm sure I'd be killed'

Parwiz and his family belong to the Hazara community, Afghanistan's third-largest ethnic group.

The Hazara mainly practise Shia Islam and have faced long-term discrimination and persecution in predominantly Sunni Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Growing up under the Taliban's influence means Parwiz and his siblings didn't have the "experience of normal children".

He says there was only one school in his village, which was constantly disrupted by Taliban members who would stop boys and girls from mixing and sometimes shut the school.

"You couldn't say anything because they've got guns and we've got nothing to fight with, so it's very scary," Parwiz says.

Parwiz Karimi

Parwiz KarimiMinorities like the Hazara "don't get a lot of protection or support" from the government, Parwiz says.

"Moving from city to city was very dangerous for us because the Taliban was in the way stopping us on occasion, taking our money and belongings.

"And if they find out you work with the government, they could kidnap you or, in the worst case, kill you."

Those difficulties led to him seeking asylum in the UK with his family, and he now lives in Wolverhampton.

"If I stayed in Afghanistan, I'm sure I'd be killed by now."

'I don't know if I'll ever go back'

For Morsal, whose surname we're not using, the past week has been "pure devastation".

"We've only just started to taste what's been 20 years of development, rebuilding and women's rights," the 23-year-old tells Newsbeat.

"We were making strides in education and positions of power - only a month ago we were celebrating Afghan excellence in the Olympics," she says.

"In the space of a few days that's completely vanished."

Morsal

MorsalShe was born in London but has visited family in Afghanistan seven times to visit her grandfather, cousins, aunties and uncles.

The thought of her family now being in danger is "numbing".

She has spoken to them in the past few days and says for now, "they're staying put in their home".

"My female cousins are not going out at all, everybody's holding their breath and waiting to see what happens," Morsal adds.

When she visited last year, Morsal made plans with her cousins for the future - but now that future is full of uncertainty.

"I don't know if I'm ever going to go back, if I can go back and what the conditions will be like if I do."

Morsal feels the guilt of those who have managed to find a safer place to live is "at an all-time high".

"You're feeling everything that your relatives and fellow countrymen and women are feeling, the anger, grief, conflict, powerlessness, hopelessness, and yet, externally, you're not there."

"Other than donating, signing petitions and circulating posts on social media, there's nothing that we can do."

The feeling of guilt is affecting Mariam, too, whose surname we're not using either.

The 20-year-old's parents and siblings were born in Afghanistan, and with much of her family still there, she is "feeling hopeless".

"I'm constantly sick with worry," she tells Newsbeat.

"I can't leave my phone because I have to check for updates on what's happening back home."

Mariam's family have told her staying inside their home is the safest option for them.

Her biggest fear is what will happen to women in the country - due to the Taliban's track record of poor women's rights.

"A lot of universities have shut their doors. A lot of women are scared to leave."

Mariam has never been to Afghanistan. She's been waiting for it to be peaceful before going.

"But will it ever become peaceful? Everyone's losing hope," she says.

Parwiz feels history shows the Taliban will remain a violent group, who rule by fear.

He thinks the progress made by 20 years of US-led occupation and military operations has "gone down the drain".

For Morsal, the future is unpredictable.

"It's been 40 years of conflict and mothers burying their sons and fathers being torn apart from their daughters.

"It's hard to know what will happen. We just want peace, because people are tired."