Norway: The country where no salaries are secret

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis week the British papers revelled in news about how much the BBC's on-air stars get paid, though the salaries of their counterparts in commercial TV remain under wraps. In Norway, there are no such secrets. Anyone can find out how much anyone else is paid - and it rarely causes problems.

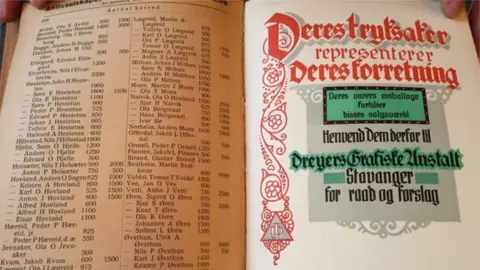

In the past, your salary was published in a book. A list of everyone's income, assets and the tax they had paid, could be found on a shelf in the public library. These days, the information is online, just a few keystrokes away.

The change happened in 2001, and it had an instant impact.

"It became pure entertainment for many," says Tom Staavi, a former economics editor at the national daily, VG.

"At one stage you would automatically be told what your Facebook friends had earned, simply by logging on to Facebook. It was getting ridiculous."

Transparency is important, Staavi says, partly because Norwegians pay high levels of income tax - an average of 40.2% compared to 33.3% in the UK, according to Eurostat, while the EU average is just 30.1%.

"When you pay that much you have to know that everyone else is doing it, and you have to know that the money goes to something reasonable," he says.

"We [need to] have trust and confidence in both the tax system and in the social security system."

This is considered to far outweigh any problems that may be caused by envy.

In fact, in most workplaces, people have a fairly good idea how much their colleagues are earning, without having to look it up.

Wages in many sectors are set through collective agreements, and pay gaps are relatively narrow.

The gender pay gap is also narrow, by international standards. The World Economic Forum ranks Norway third out of 144 countries in terms of wage equality for similar work.

So the figures that flashed up on Facebook may not have taken many people by surprise. But at a certain point Tom Staavi and others lobbied the government to introduce measures that would encourage people to think twice before snooping on the salary details of a friend, neighbour or colleague.

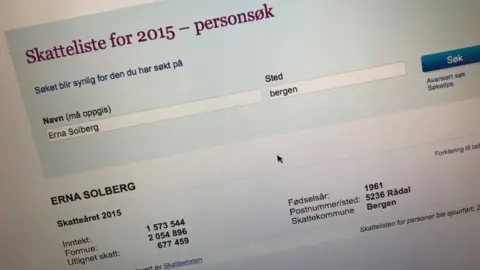

People now have to log in using their national ID number in order to access the data on the tax authority's website, and for the last three years it has been impossible to search anonymously.

"Since 2014 it has been possible to find out who has been doing searches on your information," explains Hans Christian Holte, the head of Norway's tax authority.

"We saw a significant drop to about a 10th of the volume that was before. I think it has taken out the Peeping Tom mentality."

There are some three million taxpayers in Norway, out of a total population of 5.2 million. The tax authority logged 16.5 million searches in the year before restrictions were put into place. Today there are around two million searches per year.

In a recent survey 92% of people said they did not look up friends, family or acquaintances.

"Earlier I did do searches, but now it's visible if you do it, so I don't do it any more," says a woman I meet on the streets of Oslo, Nelly Bjorge.

"I was curious about some neighbours, and also about celebrities and royalty. It could be good to know if very rich people are cheating, but you don't always know. Because they have many ways of reducing their income."

The tax lists only tell you people's net income, net assets and tax paid. Someone with a vast property portfolio, for instance, would probably be worth far more than the figure found in the lists, because the taxable property value is often far less than the current market value.

Hege Glad, a teacher from Fredrikstad south of Oslo, remembers that when she was young, adults used to queue up to examine the "enormous, thick" books of income and tax data, published once a year.

"I know my father was one of those looking. When he came home he was in a bad mood because our well-to-do neighbour was listed with little income, no assets and, most of all, a very small amount of tax paid," she says.

While she approves of Norway's transparency in this area, she notes that it can have negative effects. She has seen this in school.

"I remember once coming into school and a group of boys were very keen to tell me about the massive amounts of money the dad of one of the others in the class was making.

"I noticed a couple of other boys who usually were part of this gang had pulled back, saying little. The mood was not very nice," she says.

There have been other stories about children from low-income families who have been bullied in school, by classmates who looked up their parents' financial situation.

BBC pay

Getty Images

Getty Images

But Hans Christian Holte thinks the government currently has the balance about right.

The fact that anonymous searches are no longer permitted discourages criminals from searching for wealthy people to target.

And yet, the restrictions introduced in 2014 have not stopped whistleblowers reporting things they find suspicious.

"We like people to do searches which could help us in investigating tax evasion and the amount of tips that we get has not gone down," he says.

"Maybe the Peeping Tom part has more or less vanished, but you still have the legitimate reasons for searching and also some good effects of that openness."