Covid: How new drugs are finally taming the virus

BBC

BBCThe first patients in the NHS are being offered a new drug to help treat Covid-19. As Covid treatments are changing, fewer patients are becoming seriously ill or dying. So does this mean we are finally taming the virus?

At the start of the pandemic there were no drugs for Covid. In April 2020, I stood in a Covid intensive care ward while a doctor, in full PPE, told me they had nothing but oxygen to treat critically ill patients. I watched patient after patient on ventilators being turned on to their fronts to help their lungs take in oxygen.

It's a deeply troubling memory that will always remain with me.

Now things have changed enormously. At the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle, the critical care unit looks and feels very different. Firstly, staff are no longer in full PPE, because most wards are Covid-free. At the peak a year ago the hospital trust was caring for 90 critically ill Covid patients. Today there are just three.

It is now the exception, rather than the norm, for patients to go on a ventilator. Hospital stays are much shorter and survival rates have improved significantly.

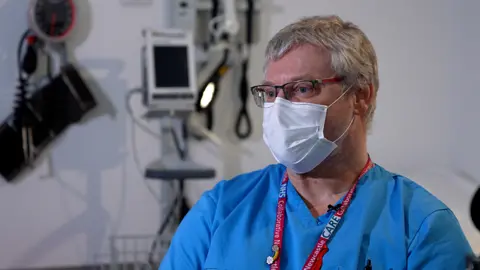

"Two years ago we had nothing,'" says Dr Matthias Schmid, head of infectious diseases at the RVI, who treated the UK's first Covid patient at the end of January 2020.

"Now we have a range of treatments available which reduce the severity and prevent death in a huge number of patients."

They include the cheap anti-inflammatory steroid dexamethasone, the first drug proven to save the lives of people seriously ill with Covid, which was discovered through a ground-breaking NHS trial.

"It's feeling more normal for us," says Dr Miriam Baruch, intensive care medicine consultant.

"It's really nice that we can train our doctors for the variety of patients that we get."

Of course the biggest single advance has been the introduction of highly effective vaccines. While they are less effective at preventing people from catching the latest variant Omicron, they do give very strong protection against severe disease.

"We've had some very sick patients who've come in with Omicron but the majority of those are unvaccinated," says infectious diseases consultant Dr Ashley Price. He says without vaccines Omicron would have caused "vast numbers" of hospital admissions.

And there are now treatments to defend the most vulnerable.

David Howarth is a day patient. After long periods shielding through the pandemic, he has finally caught Covid. Because he is immunosuppressed he has had four doses of vaccine. But those with weakened immune systems often don't get as much protection from the jabs, so are more vulnerable once infected.

But he's feeling fine and is not worried. David, 59, is getting a one-off infusion of Covid-fighting antibodies.

"I was only diagnosed with Covid yesterday, and I'm receiving this already," he told us. "It'll boost my ability to fight the virus. It will give it a helping hand."

The drug, sotrovimab, is a monoclonal antibody - synthetic proteins which stick to coronavirus to prevent an infection from getting established.

In trials of vulnerable patients it cut their risk of hospital admission and death by 79% - 100,000 doses of sotrovimab, are on order for the NHS.

The one thing still missing here is visitors, but the hospital is just beginning to ease restrictions.

The focus now is on keeping patients from ever needing hospital treatment. That's where antivirals come in.

There are thousands of medicines on the shelves in the Royal Victoria Infirmary's automated dispensary, which is the size of a couple of shipping containers. When one of the pharmacists types in the name of a drug, the robot arm races down the central aisle, selecting the medicine and dropping the pack down a chute.

The box of pills selected is called Paxlovid - it's an antiviral which, in trials, cut Covid hospital admissions by 88%. The treatment is being dispatched to high-risk patients across the UK who have just tested positive.

Through the Antivirals Taskforce, the government has procured nearly five million doses of Paxlovid and another antiviral, molnupiravir.

Both are designed to prevent a Covid infection from turning serious and form part of the armoury of treatments we now have against Covid.

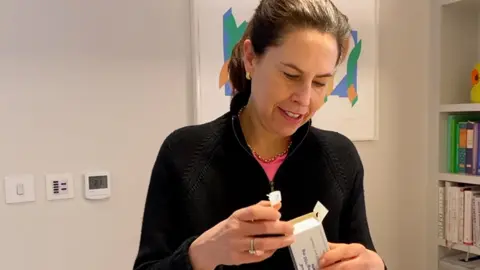

Emily Goldfischer, 51, from west London, is one of the first patients in the UK to take Paxlovid.

She is immunosuppressed and has also had four doses of vaccine. She contacted her hospital team when she tested positive on a lateral flow.

A prescription for Paxlovid was couriered to her home the same day from Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

"I've taken it for about two days now and I'm already feeling much better," she told us. "And it's been quite reassuring that I've been able to get this medication so quickly from the NHS."

There are still more than 12,000 Covid patients in hospitals across the UK. And there could still be new and concerning variants which cause further waves of infection. If this pandemic has taught us one thing it is to avoid making rash predictions. Coronavirus will flare up again and continue to pose a threat, especially to the unvaccinated and those who have serious underlying health conditions.

Even though the Covid hospital admissions have fallen sharply, there is the growing problem of long Covid. Last month a record 1 in 50 people in the UK said they were living with lingering symptoms of Covid.

But the combination of effective vaccines and targeted medicines look set to help keep Covid in check and allow the NHS and society to plan for a future no longer dominated and disrupted by coronavirus.

Covid will not disappear completely, but even if a new more deadly variant emerges it should be managed by a combination of vaccines and the increasing range of effective drug treatments.

Covid has been the biggest challenge ever faced by the NHS. Two years on, hospitals can begin to plan for a future not completely free of the disease, but one where it no longer dominates healthcare and society.