Covid: Why are UK cases so high?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHealth leaders in England have called for Covid restrictions to be re-introduced ahead of winter, as cases rise.

Thanks to the vaccine, getting infected is now much less likely to land you in hospital. But soaring cases - which are outstripping some European nations - are still proving a cause for concern.

The more virus there is about, the more chances there are for it to break through the defences of vaccines, reach vulnerable people and put pressure on health services.

What do the figures show?

The number of people testing positive for Covid in the UK has been rising in recent days to more than 50,000 cases in one day.

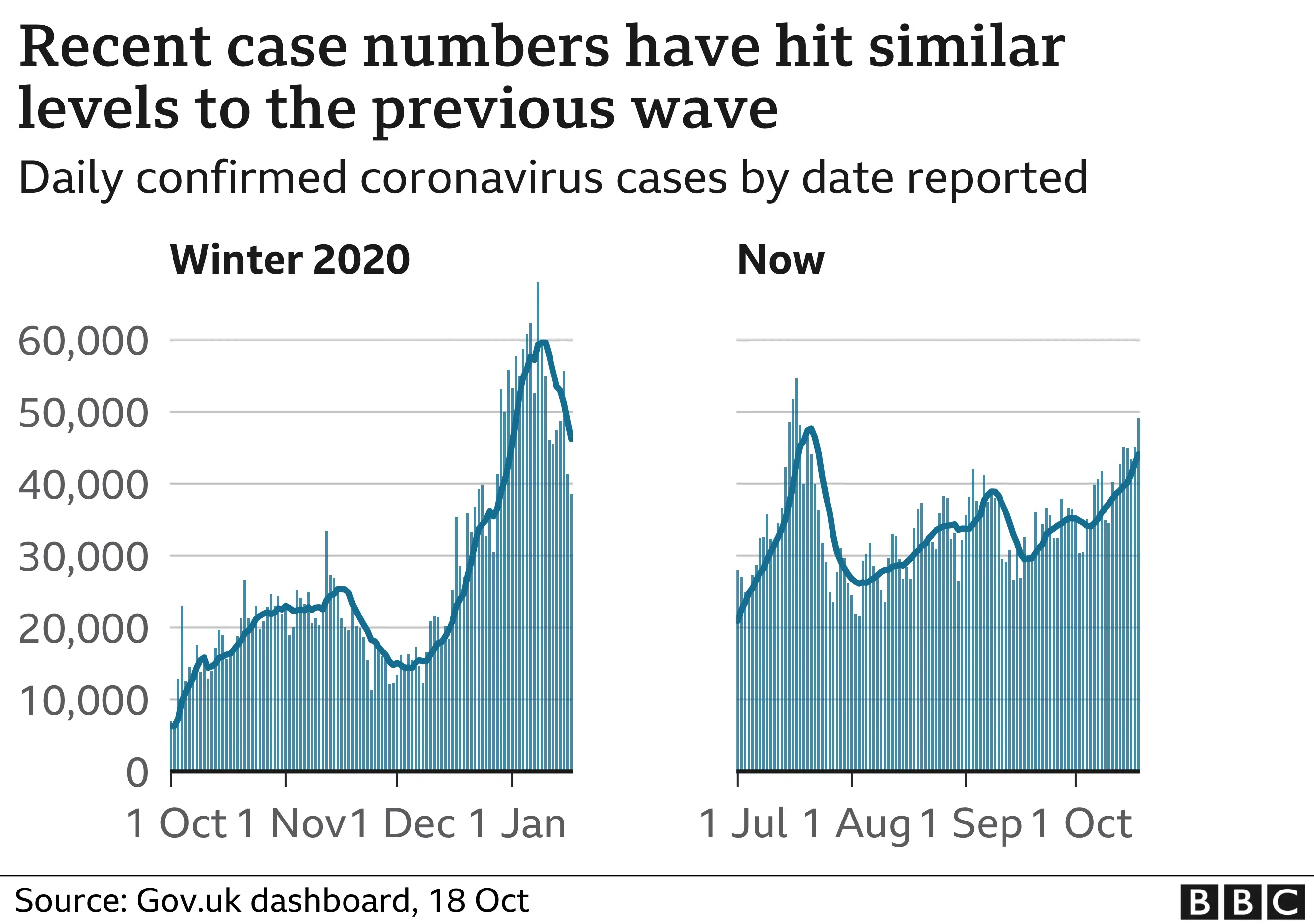

Over the past three months there have been roughly as many cases as there were over three months last winter, which allows us to compare the two time periods.

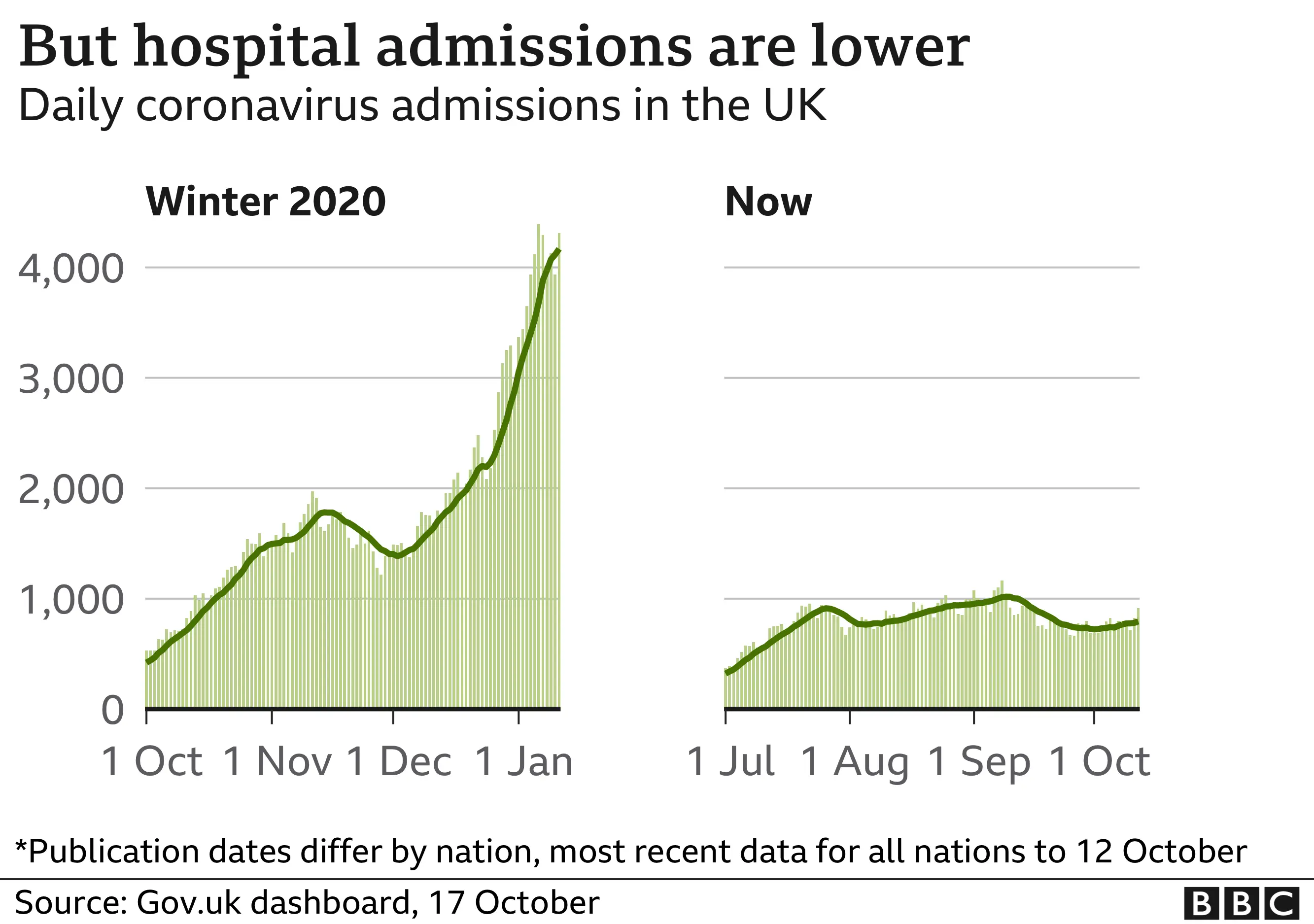

Between July and October this year, there were just over three million cases, with 79,000 people ending up in hospital.

Between October and January last year, there were just over 2.7 million cases, but more than 185,000 people needed hospital treatment. This was before vaccines were widely available.

These two charts show us the effect of the removal of restrictions and the rise of the Delta variant on the one hand in driving up cases, and the vaccination programme on the other in pushing down admissions.

In England, unvaccinated people were at least three times as likely to need hospital care as vaccinated people, according to the most recent Public Health England figures for the previous three weeks.

In the oldest group - the over-80s - 141 people in every 100,000 unvaccinated people ended up in hospital with Covid compared with 54 in every 100,000 vaccinated people. In the youngest - the under-18s - four unvaccinated people in every 100,000 needed overnight hospital treatment compared with zero in the vaccinated group.

Deaths are also being kept at a much lower level than when cases were previously this high.

So what do we know about what's driving the rise in cases?

Less mask-wearing?

UK residents were significantly more likely than people in Germany, France, Spain and Italy to say they no longer wear a face mask or covering.

Covid cases are higher in the UK than in any of those countries - but we can't necessarily say that one is causing the other.

Study after study has shown face masks can help stop the virus from being passed between people. When it comes to measuring how much mask wearing reduces an outbreak, though, it's a lot more difficult to pin down.

That's because it's hard to untangle it from all the other things going on at the same time, like how much people choose to mix with each other.

People in Sweden and the Netherlands were more likely than the UK to say they never wore a mask, according to a survey by Imperial College London. But these countries have fewer confirmed Covid cases than the UK.

Within the UK, Scottish rules still require masks in most indoors places, while English ones don't. And people in Scotland - asked by the Office for National Statistics - were a bit more likely to say they had worn a face covering in the previous seven days. Yet the nation also saw a spike in hospital admissions in recent weeks.

Looser rules, more mixing?

The UK relaxed many restrictions sooner than most of the rest of Western Europe. People in England, Wales and Scotland have been able to go to nightclubs and attend gatherings of unlimited numbers of people since the summer, unlike in many other countries.

Imperial College survey data suggests people in the UK are slightly more likely than some of their nearest European neighbours to take public transport, and less likely to avoid going out.

The latest survey of contacts and mixing in the UK found that there had been relatively little change in recent weeks, with contact rates for children similar to those at the start of term.

There has been a gradual increase in the number of employees going to work in person, although it's still quite low, with only about half of employees going into their workplace if it was open.

Waning immunity?

The UK surged ahead in its rollout of the vaccine. That's undoubtedly saved many lives by preventing severe cases of Covid, but this early progress could give a clue as to why the country is facing higher cases now.

A study - of Covid test results of vaccinated people who logged their symptoms in an app - suggested the vaccine's protection against catching the virus wanes significantly after five or six months.

In Israel, which originally led the world in terms of population vaccinated, scientists analysing their data said a spike in cases was down to falling protection from the jab. And cases levelled off once enough older people had been given a booster dose.

Boosters are now being given to older people in the UK - 3.7 million doses had been administered in England by 17 October.

Importantly, protection against severe disease seems to remain high six months after vaccination.

It's true that the more infections are circulating, the higher the risk some people will end up seriously ill, even when most have been vaccinated. That's probably why hospital admissions in the UK are higher now than they were early in the summer when cases were lower.

But when you look at the overall numbers, we are seeing far fewer hospital admissions now than when cases were last this high and most people weren't vaccinated.

Stalled vaccine rollout?

The UK's quick start in its vaccination rollout has stalled in recent months. Its rate of fully-vaccinated people no longer ranks in the top 10 countries with a population of at least one million.

In the first two weeks of October, the proportion of the British public aged 12 and over who had received at least one dose of the vaccine barely moved.

A government spokesperson said: "The vaccination programme has significantly weakened the link between cases, hospitalisations and deaths, and will continue to be our first line of defence against Covid-19.

"We encourage those who are eligible for a booster jab to come forward to ensure they have this vital extra protection as we approach winter."

The UK's vaccination rate is slightly skewed by the low uptake of doses by children. Vaccines for 12-15-year-olds in the UK started on 20 September. So far, 15% of 12-15-year-olds in England have received one shot. This is compared to Israel, where more than half of 12-15-year-olds have had at least one shot.

Most other European countries are now vaccinating over-12s, including France, which started rolling it out in June.