Should schoolchildren still have to self-isolate?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore than a quarter of a million children are absent from school in the UK because of coronavirus, prompting calls for a different approach to testing and quarantining of pupils that puts children's needs first.

With children at extremely low risk from the virus and more than three out of every five UK adults now fully vaccinated, is it time for a change in policy?

'Detrimental effect'

Over the past week, in England alone, absences due to Covid have nearly trebled - with more than 170,000 pupils self-isolating as close contacts, most in secondary schools.

According to Dr Michael Absoud, from King's College London, missing school will have a detrimental effect on children's mental and physical development, particularly those with learning disabilities or from poorer families.

The most vulnerable have missed out on much-needed support and socialising, as well as their education, which has "set them back hugely", he says.

"We are at a different stage in the epidemic now - there needs to be an alternative to isolating contacts of positive cases," Dr Absoud adds.

Missing out

Children's mental-health experts have long campaigned for the harmful knock-on effects of the pandemic to be recognised.

This is even more critical now, they stress, when the most vulnerable have been vaccinated and lives are returning to normal.

Parents are also expressing their anger and frustration on social media, saying families' plans are being disrupted and children are missing out on sports days, exams, end-of-term events and trips.

"Children must be the most isolated and tested group," secondary-school parent Liz Cole, co-founder of campaign group UsForThem, says.

"Where is the roadmap for children's lives?"

As the Delta variant, first identified in India, pushes up the case numbers, young adults and school-age children are seeing the sharpest increases - because they are, broadly, the least vaccinated groups.

Regular rapid testing of schoolchildren means asymptomatic cases, more likely in children, can be detected early to reduce spread.

But this often results in whole classes or year groups having to self-isolate too, particularly in areas with high case rates.

'Unnecessary spread'

Many scientists say there is no easy way to resolve this issue when cases of the virus are rising and more than one out of every three adults has yet to have two doses of the vaccine.

"You can't ignore Covid completely and we don't know yet whether frequent daily testing is as effective as isolating whole classes," Dr Damian Roland, paediatrician and honorary associate professor at the University of Leicester, says.

"So we are stuck trying to keep children at school but also avoiding unnecessary spread."

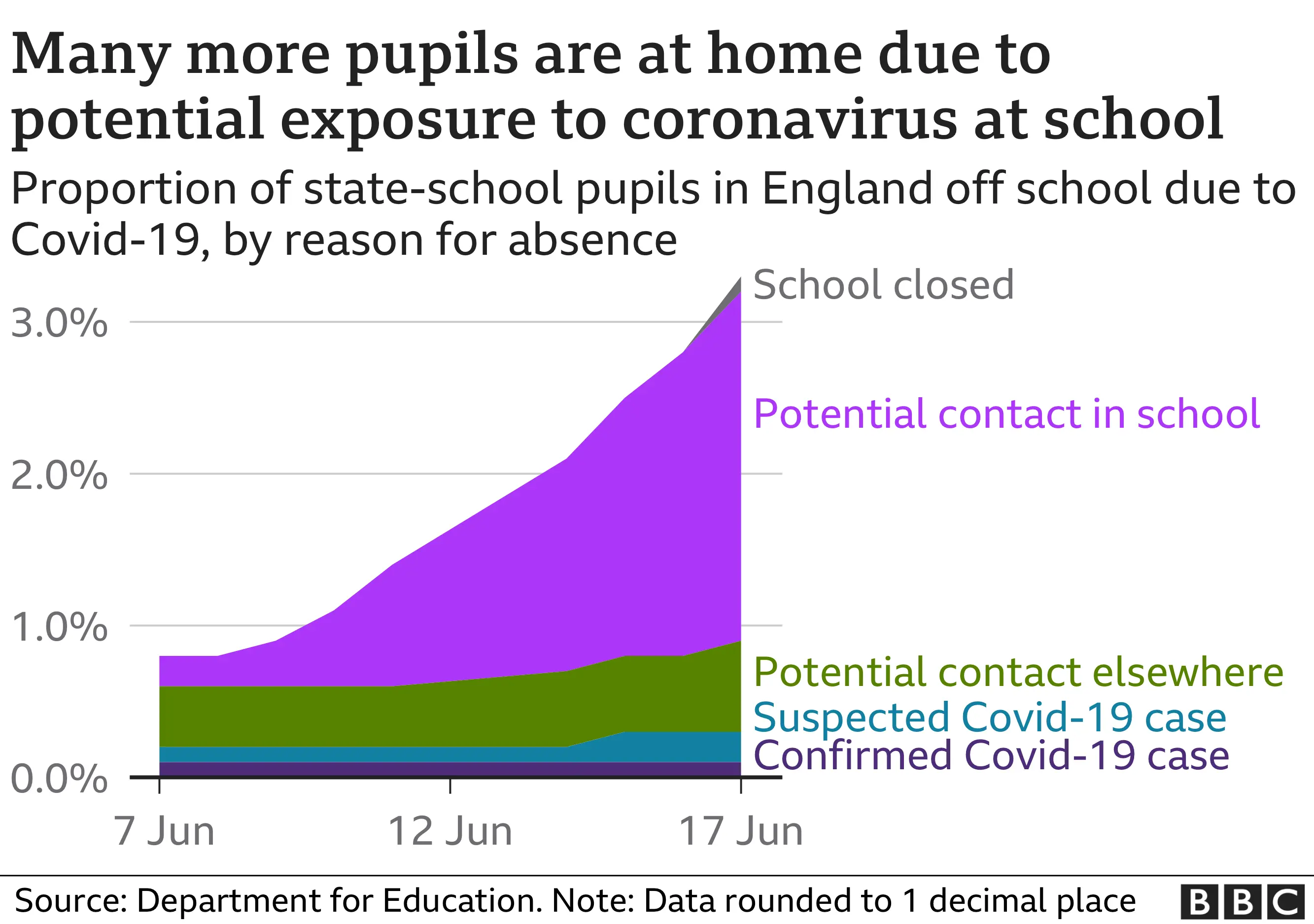

The latest official figures, for 17 June, show, in England alone, 2.7% of primary and 4.2% of secondary schoolchildren are absent because of Covid.

That includes;

- 9,000 with a confirmed case

- 16,000 with a suspected case

- 172,000 self-isolating because of potential contact with a positive pupil in school

- 42,000 self-isolating because of potential contact with a case from outside school

In Scotland, 20,700 pupils are not in school for Covid-related reasons, with 17,800 of those self-isolating. Two primary schools are closed and several others at risk of closure.

And if a pupil has symptoms, tests positive or is a close contact of someone who does, they must stay at home for 10 days.

A government-led trial is under way to work out whether the daily testing of pupils who are close contacts is a better option than self-isolation - but that will come too late for this school year.

In the meantime, schools with positive cases report them to the Department for Education and contact their local authority's public health team for advice.

Shed virus

Many say the current approach is the right one because it cuts the risks of airborne transmission in schools, which tend to be poorly ventilated and where masks are no longer mandatory.

"Children can get infected and shed virus at even higher viral loads for even longer than adults," consultant virologist Dr Julian Tang says.

And asymptomatic cases can cause more infections because they often remain undetected.

But health officials say spread of the virus in schools has always been low and there is no evidence schools are causing outbreaks. Instead, they appear to be reflecting levels of the virus in their local communities.

Data from the government-led trial, in 200 schools and colleges, should answer the question of how many close contacts of infected children actually become infected themselves - and give ministers some idea of how rules could change in the future.

The ultimate goal is to keep schools and colleges open and prevent children's education from being disrupted, while also reducing the risk of community spread.

- FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

- SCHOOLS: When will they reopen?

- COVID IN SCHOOL: What are the risks?

- VACCINE: When will I get the jab?

- NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?