Indian variant: Why is UK taking a risk with the variant?

PA Video

PA VideoA Covid variant first identified in India and spreading in parts of the UK, has threatened to derail Britain's plans for a return to normality. In allowing the latest lockdown easing, the government stands accused of recklessness. So why has it taken the risk?

Last Thursday 39 of the country's leading scientists and health experts gathered - via video conference - to discuss the escalating situation.

At the Sage meeting they were presented with a paper by the government's modelling committee, that made alarming reading.

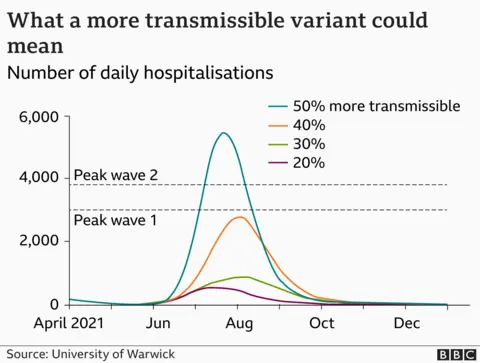

There was, the document said, a "realistic possibility" that the Indian variant was 50% more transmissible than the UK variant which had been responsible for the deadly winter wave.

If this was the case, the modellers said, there was the potential for a summer wave that would be even worse. It could not have been more alarming.

One of those present, Sir Jeremy Farrar, said they faced the "hardest policy decision" of the pandemic - but in the end moving ahead with the roadmap was a reasonable call considering the context.

Huge uncertainty over Indian variant

Dig beneath the headlines and a more complex picture emerges than the 50% figure which grabbed headlines. The term "realistic possibility" is actually a defined phrase, one of several on a sliding scale used by these committees.

It means there is basically a 50:50 chance the modellers are right about the variant being as much as 50% more infectious.

Along with the modelling presented on Thursday, several other pieces of evidence were looked at. Public Health England (PHE) had been gathering data on what had been happening on the ground as part of the test-and-trace programme. It cast doubt on the 50% figure.

A number of things did not add up to its analysts.

Some of the data on "secondary attack rates" - the chances of an infected individual passing the virus on to someone - suggested the variant may be much less infectious than feared.

And it did not seem to be behaving in the same way in every region. A significant cluster has been found in London, but that had not risen at the same speed as it had in Bolton.

The degree of extra transmissibility makes a big difference. A variant that is 20% more transmissible has a much smaller impact on hospital cases.

The sheer volume of imported cases from travellers returning from India - it was argued - could have caused a spike, and explain a big chunk of what appeared to be the extra infectiousness.

One of the problems in nailing how infectious a variant is, is the lag between getting a positive diagnosis from a patient and establishing which variant of the virus caused it. It takes about a week.

So the picture we are looking at is, in fact, out of date.

Another sign being analysed is the latest raw infection rates in hotspot areas - before samples are sequenced. There are now some tentative signs the rapid rises may have started slowing, offering support to the hope the 50% extra transmissibility figure is too high.

What is more, some at the meeting believe the models were too pessimistic - suggesting the vaccination programme will stem the rise in infections or at least limit the scale of serious illness more than the modellers predicted.

"There is a huge degree of uncertainty with this - we have spotted this early and we are still trying to work out what exactly is going on with this variant," said one of those working on analysing it.

The 'agonising' decision

Naturally with so much unknown, there was much debate both at Sage and in other meetings that took place on Friday, about how to respond.

The nuclear option of delaying indoor mixing, due to re-start on 17 May, was discussed. Doing so could buy more time to study the emerging data on the Indian variant, while allowing for more vaccine rollout.

But the government was already committed - it had been confirmed last Monday - and so it was ruled out, although in Scotland extra restrictions have stayed in place in Glasgow and Moray.

"It was agonising. There was just not enough evidence there to justify the move," said one of the people close to the decision-making. "But keeping restrictions comes with a cost too."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere have been plenty of experts questioning whether Monday's unlocking was worth the risk, including members of Independent Sage and the British Medical Association.

But it is worth noting that these are the same critics who warned against the full re-opening of schools in March, saying it would lead to a surge. They also said the January lockdown was not tough enough to bring cases of the UK variant down and objected to delaying the gap between vaccine doses to 12 weeks with the BMA calling for the gap to halved.

"We know if it goes wrong the critics will say 'we told you so'. But... those people criticising now have been wrong before," another of those involved in the meetings last week said.

That, of course, is the price that comes with power - and if cases and, crucially, hospitalisations do take off it will look like a mistake.

This won't be the last variant dilemma

But this is unlikely to be the last time the UK is faced with such a situation.

Much has been made, understandably, of the decision not to put India on the red list sooner. But this is not just a UK problem - the Indian variant has been found in 50 countries across the world, including Australia.

Yes, the UK has identified the most cases after India, but it does do nearly half the world's genomic sequencing. Another of the scientists who took part in the Sage meeting last week, Prof John Edmunds, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has said the spread of the variant could not have been stopped, only delayed "a little bit".

Prof Mark Woolhouse, an expert in infectious diseases, at Edinburgh University, agrees. "This situation was entirely expected. In six months time I'm sure we will be talking about another variant," he says.

He is more worried about the South Africa variant given it seems more able to escape some of the effect of the vaccines - although the evidence is pointing to a rather more limited escape than was originally feared.

Variants, unfortunately, will be a fact of life in this pandemic until the virus is brought under control across the world. But that does not mean there is no way out or that the UK, with its progress with vaccination, cannot keep moving towards a more normal way of life.