Is Europe's AstraZeneca jab decision-making flawed?

PA Media

PA MediaA number of countries have decided to suspend use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine as a precaution following reports that some people have suffered blood clots after being given the jab.

But is it a case of being too cautious? Are these nations missing the bigger picture?

The decision has been made on the basis of the precautionary principle - a well-established approach in science and medicine that stresses the need to pause and review when evidence is uncertain.

But in a fast-moving pandemic, when each decision can have major consequences, it is an approach which can sometimes do more harm than good.

Cause or coincidence?

The data supplied by AstraZeneca shows there have been 37 reports of blood clots among the 17m people across Europe who have been given the vaccine.

But the key question that has to be asked is whether this is cause or coincidence? Would these clots have happened anyway?

Adverse events like this are monitored carefully, so regulators can assess if they are happening more than they should.

The 37 reports of clots are below the level you would expect. What is more, there is no strong biological explanation why the vaccine would cause a blood clot.

It is why the World Health Organization and UK drugs regulators have all said there is no evidence of a link.

Even the European Medicines Agency, which is looking into the reports, has suggested the vaccine should continue to be used in the meantime given the risk Covid presents to health.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the decisions by individual nations to pause their rollouts have baffled experts.

Prof Adam Finn, a member of the WHO's working group on Covid vaccines, says stopping rollout in this way is "highly undesirable" and could undermine confidence in the vaccine, costing lives in the long-term.

"Making the right call in situations like this is not easy, but having a steady hand on the tiller is probably what is needed most."

Has Europe got a problem with the vaccine?

This is not the first time countries in Europe have exercised caution about the AstraZeneca vaccine.

The precautionary principle was adopted by Germany, France and others when they did not initially recommend use of the vaccine for the over-65s. French President Emmanuel Macron even called it "quasi-ineffective".

The over 65s decision has now been reversed, but the impact is still being felt it seems.

Germany and France have supplies of the vaccine going to waste, with both countries having used fewer than half their supplies of the AstraZeneca jab so far. It has left them far more reliant on the Pfizer vaccine than the UK is.

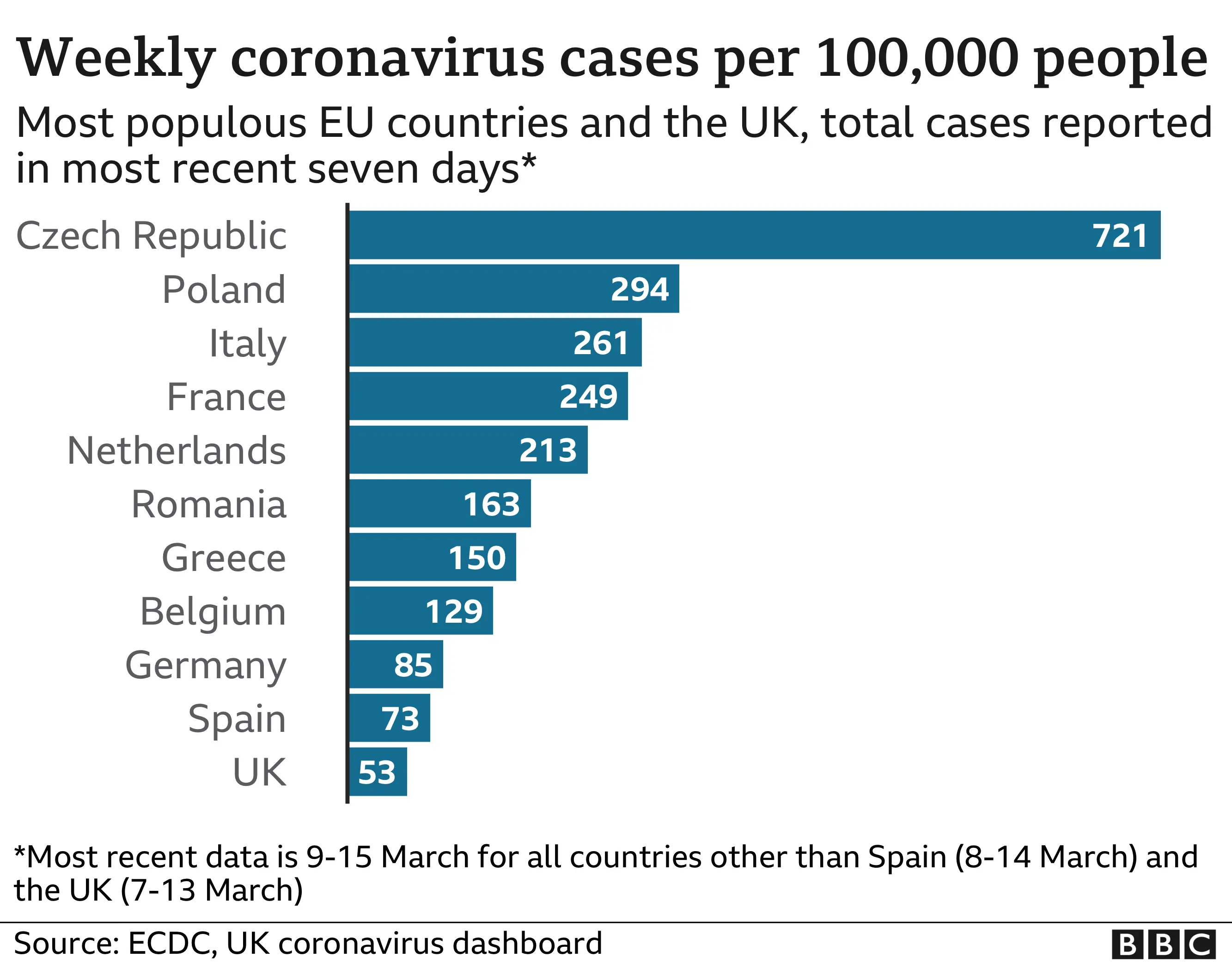

And this is threatening to have deadly consequences. France, Germany and the other major European nations all have higher rates of infection than the UK, and face the prospect of things getting worse before they get better.

BBC News

BBC News

If you look back at the decision on the over-65s, you can see how it was made. The way the trials had been organised meant there was limited evidence on its use in older age groups.

The organisers had wanted to recruit younger adults in the initial stages for safety reasons, so when it came to regulators assessing infection rates the data was not yet ready for older people.

But there was evidence from blood samples that the vaccine had prompted a strong immune response in the older age groups. So there was no reason why the vaccine would not work in older age groups - it was just that insufficient time had passed to gather the evidence in the real world.

There was also a problem interpreting results because of the way the trial was run. There was a lack of consistency across the different sites used.

Protocols and practices followed varied across each, including the use of a half-dose in one.

Some have described it as four trials within a trial. It created a somewhat messy set of data to interpret.

Why bold decision-making may be best

The UK looked past this and took the leap though - and within months was reporting "spectacular" results in reduced levels of serious illness in the over-80s.

It was this pragmatic approach to decision-making that also led the UK to recommend up to a three-month gap between doses.

This caused much controversy when it was announced at the end of December.

The Pfizer vaccine was not tested like this in trials - the interval was three weeks.

But again, the absence of evidence did not mean the move would not work or was not based on logic.

The AstraZeneca trials did have longer intervals for some participants, which seemed to make it more effective, while evidence on the Moderna vaccine, which is a similar type of jab to Pfizer, also suggested it could work.

It is also well-established that with two-dose vaccines, most of the protection is provided by the first dose, while the second boosts that and provides more long-lasting protection.

With cases rising rapidly at the time, the UK was clear the benefit of maximising available vaccine supplies to provide some protection to more people was the right step even if the trial evidence did not directly support it.

Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, an expert in understanding risk at Cambridge University, says it shows that sometimes you have to look beyond the precautionary principle and be bold in your decision-making.

"The precautionary principle favours inaction as a way of reducing risk. But the problem is that these are not normal times and inaction can be more risky than action."

What is needed in circumstances like these, according to Sir David, is to work out what is most likely on the balance of probability. That requires looking at both the direct and indirect evidence and the context those decisions are being made in.

"Sometimes it can be harmful to wait for certainty. Not vaccinating people will costs lives."