Is Covid at risk of becoming a disease of the poor?

Google

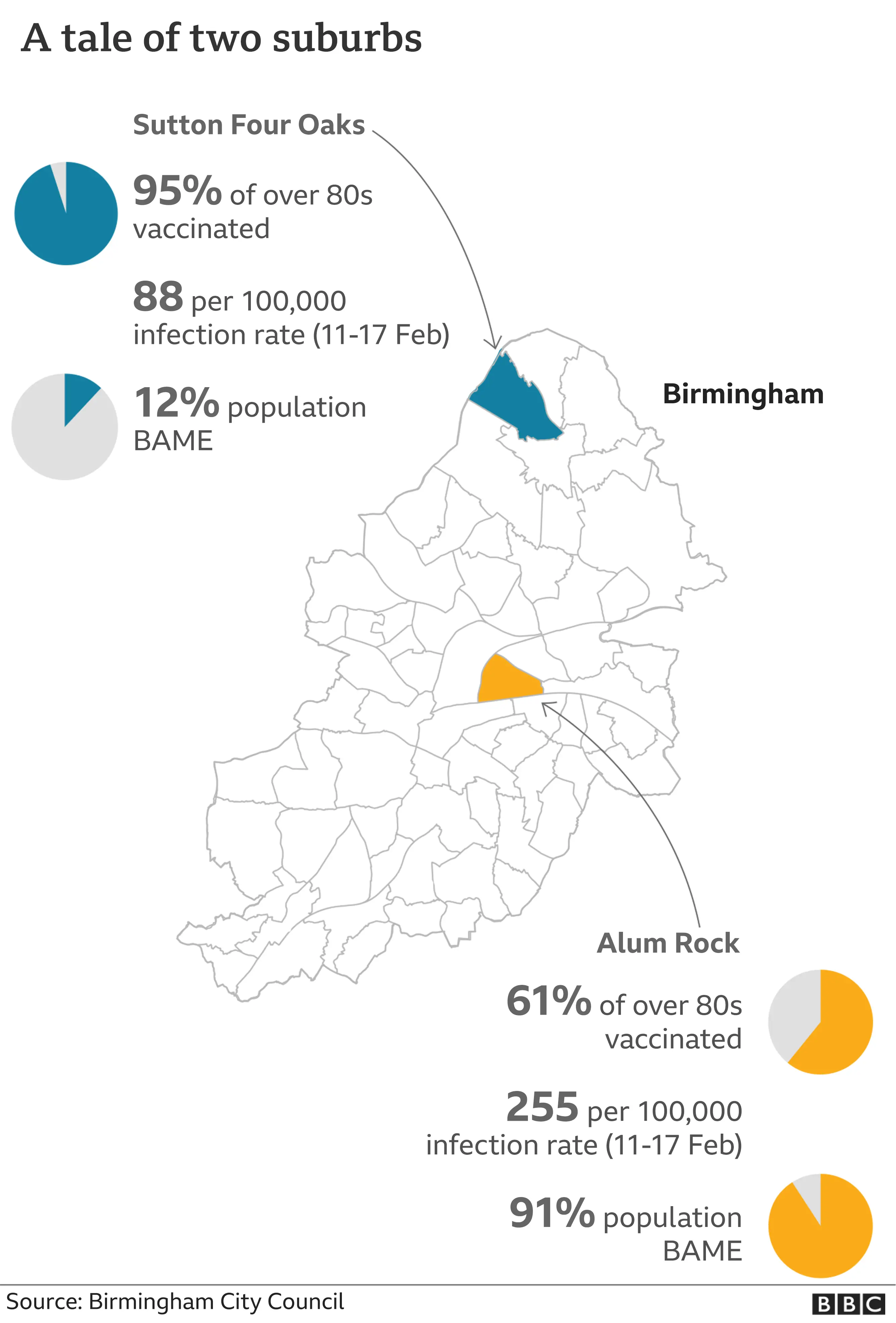

GoogleAlum Rock is an inner city suburb of Birmingham. It is deprived and ethnically diverse, with a large Pakistani community.

The area has seen high rates of infection and yet it has among the lowest number of people coming forward for vaccination. Just six in 10 of those aged over 80 have had the jab.

A few miles to the north is Sutton Four Oaks, an affluent area with detached houses and tree-lined streets. Infection rates have been three times lower in recent weeks, but close to 95% of over-80s have been vaccinated.

Local MP Liam Byrne spoke about the problem in the House of Commons this week. It is, he told MPs, "a story of two nations - rich and poor".

This is not unique to Birmingham. It is a pattern that is being repeated across the country. The people who are most at risk from the virus are the ones, it seems, who are least likely to come forward for vaccination.

Picture emerging 'enormously worrying'

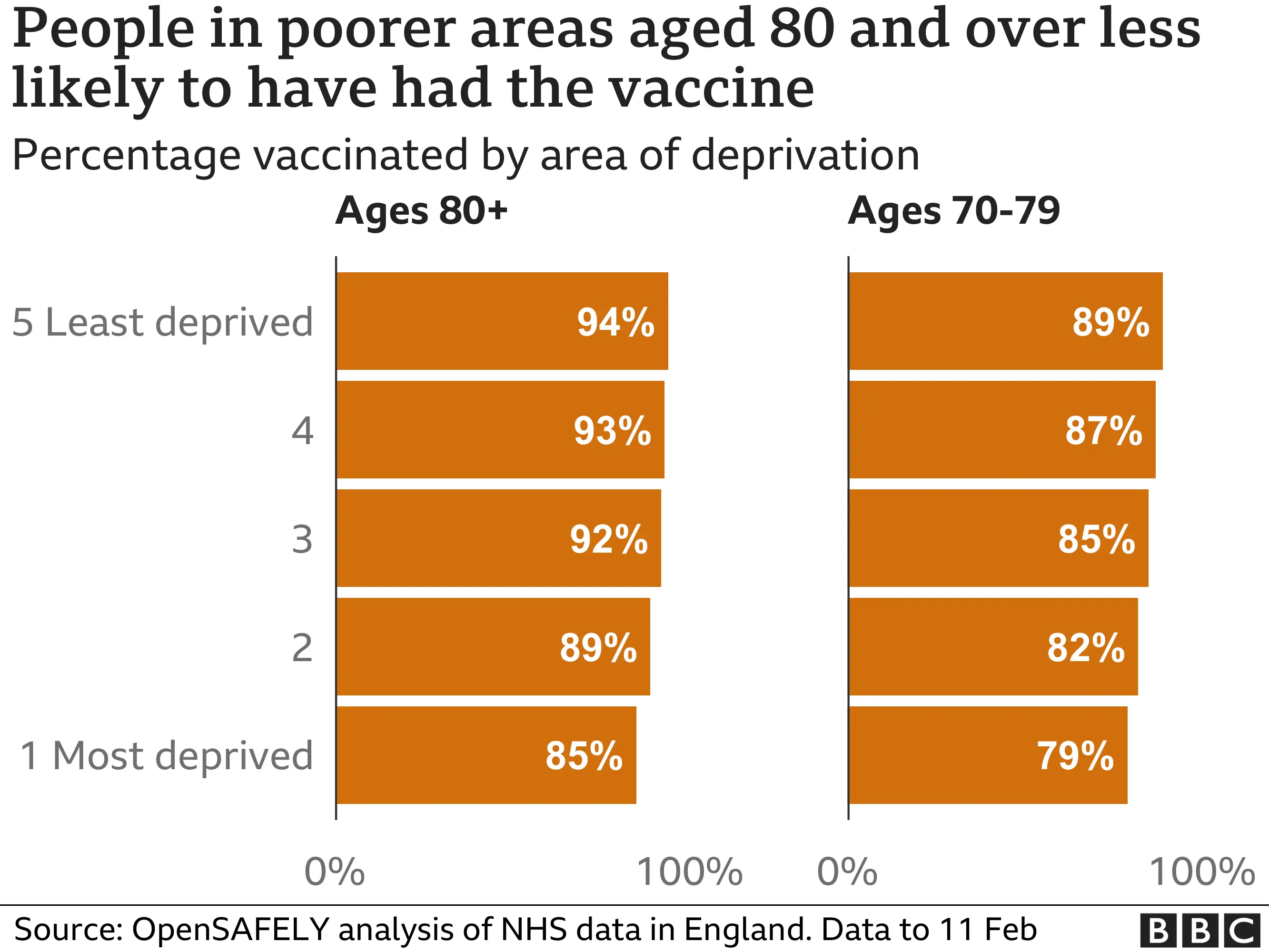

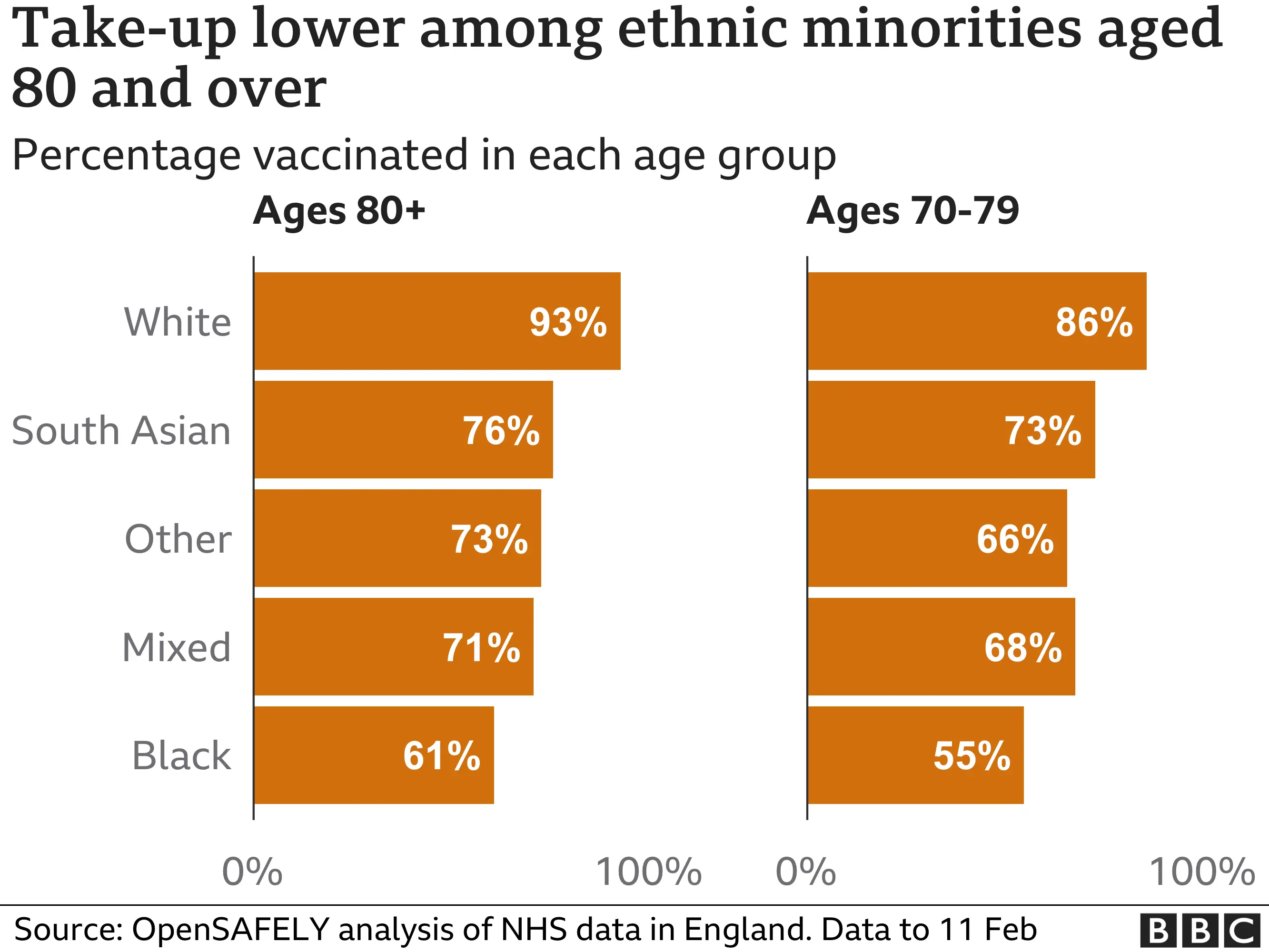

Detailed data on uptake down to a community level is not being published by the government to the frustration of many - the figures for Birmingham were published by the council. But what information is available suggests the poorest and most ethnically diverse communities (there is a huge overlap between the two) are seeing the lowest levels of uptake.

Sir Sam Everington, who is a GP in the east London borough of Tower Hamlets, one of the poorest areas in the city, says he has seen this pattern emerging, which he describes as "enormously worrying".

He believes the vaccination programme needs to be taken out into local communities more, instead of relying on mass vaccination centres and large community hubs.

He would like to see local GPs, nurses and the community working hand-in-hand, taking the vaccine out into community settings.

It is, to be fair, something that has already been recognised by the government. It has provided £23 million of funding under the Covid Champions Fund, to help councils address some of the problems.

Councils like Birmingham are using it to work with community leaders, training them to speak informatively and confidently about the benefit of vaccination. Some areas are setting up pop-up clinics in neighbourhoods where uptake is low. They have been run in mosques, churches and community halls.

But there is a barrage of misinformation out there, with videos and information circulating on the internet and social media claiming the vaccines cause fertility problems, contain animal products and even alter a person's DNA.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate estimates that the biggest English-language anti-vaxxers social media accounts enjoy a global following of 59 million, with the top 147 accounts increasing their reach by nearly a fifth in the last year.

These myths need busting. But Dr Farzana Hussain, of the NHS Confederation, which represents GPs in charge of the vaccination programme, says it is also important to recognise people have legitimate "questions and fears" too that they want addressing. "It is not always resistance. It's been rolled out very quickly - [they ask] how can it be safe?"

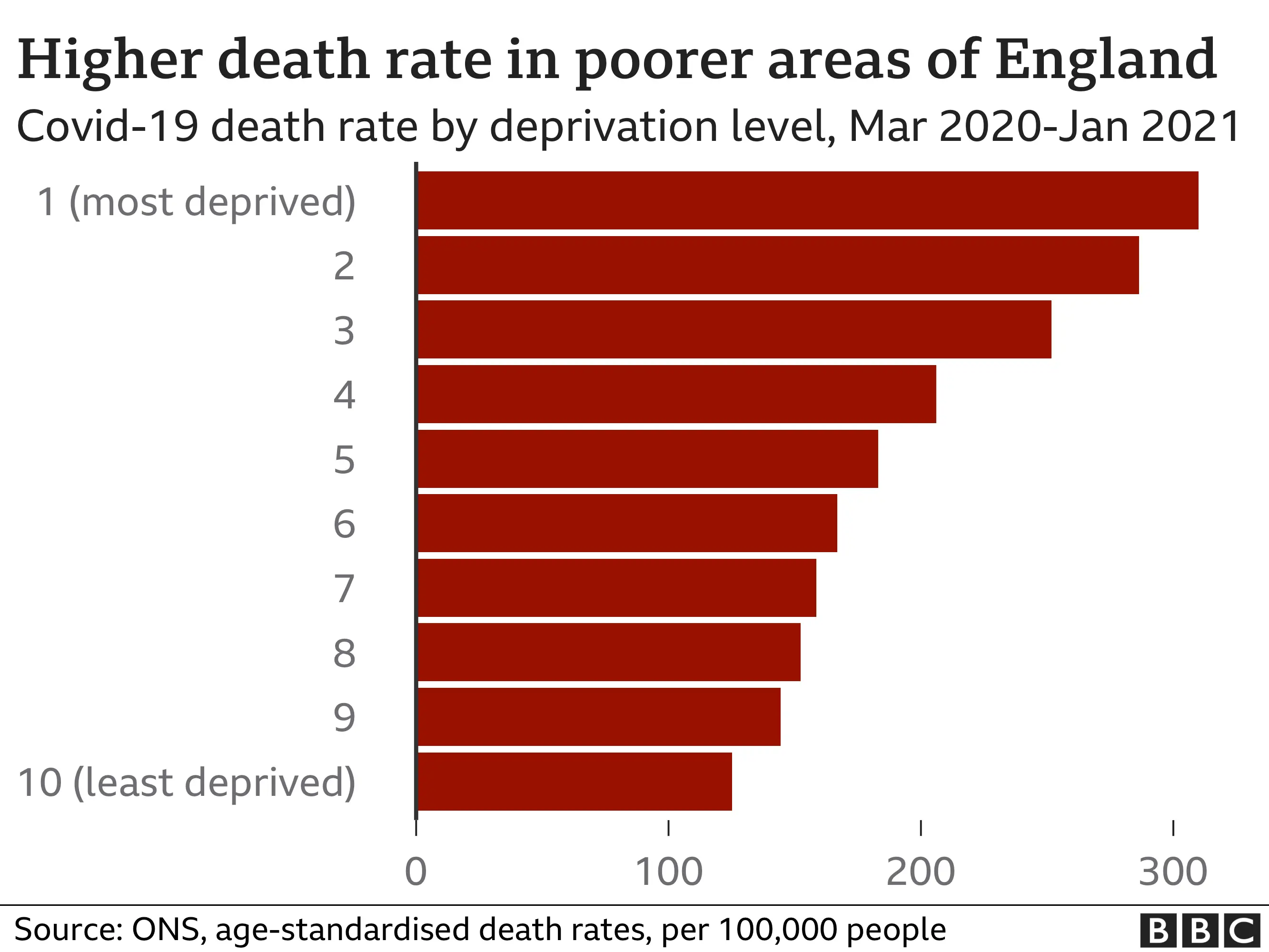

Infections and deaths higher

But this is not just about vaccination. It has been well-documented that those in more deprived and ethnically diverse communities have been at greater risk from the virus. Work by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that those living in the most deprived neighbourhoods have been more than twice as likely to die from Covid as those in the least deprived - the reasons for this are complex, ranging from greater exposure to higher levels of poor health.

And that is likely to continue. Infection rates are still circulating at higher levels in the poorest neighbourhoods. React, one of the government's surveillance programmes, showed that when the second wave peaked in January, infection rates were 50% higher in the most deprived areas than in the least deprived. Ethnic minority groups were twice as likely to be infected than their white peers.

Dr Sakthi Karunanithi, director of public health in Lancashire, believes this combination of lower vaccine uptake and higher infection levels could further "entrench inequalities" for years to come, with the virus clustering in the most deprived neighbourhoods.

He wants the government to "progressively advantage" such communities when it comes to the response to Covid. He says this could include everything from prioritisation in vaccination rollout, to better financial support to self-isolate, pointing out they work in higher risk professions where they have more frequent contacts, and are less able to work from home.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWithout this, Dr Karunanithi is concerned that deprived areas face the prospect of cases rising when lockdown lifts or having tougher restrictions for longer, further disadvantaging communities.

Analysis by the Health Foundation has shown that even before the pandemic, people in the poorest tenth of the country were three times more likely to die prematurely than some in the richest tenth. The pattern emerging with Covid, the think-tank warned, was likely to increase that gap even further.

This is a "real risk", says Prof Jackie Cassell, a public health expert at the University of Brighton. "The government is talking about the civic duty of people to do their bit, but that is harder for some than others."

She says there are so many complex factors at play. "If you haven't got a car or you are in ill health, it may not be easy to get to a vaccination centre. We can't assume it is because people do not want to be vaccinated - it may be about access.

"And if you live in crowded housing, are on a zero-hours contract or have to provide care to an elderly relative, isolating when you have symptoms is not easy. If we don't find a way to address these challenges, it will be devastating for the most deprived. They will be left behind."

Follow Nick on Twitter