Covid: Teachers 'not at higher risk' of death than average

Google

GoogleTeachers were not at significantly higher risk of death from Covid-19 than the general population, Office for National Statistics figures suggest.

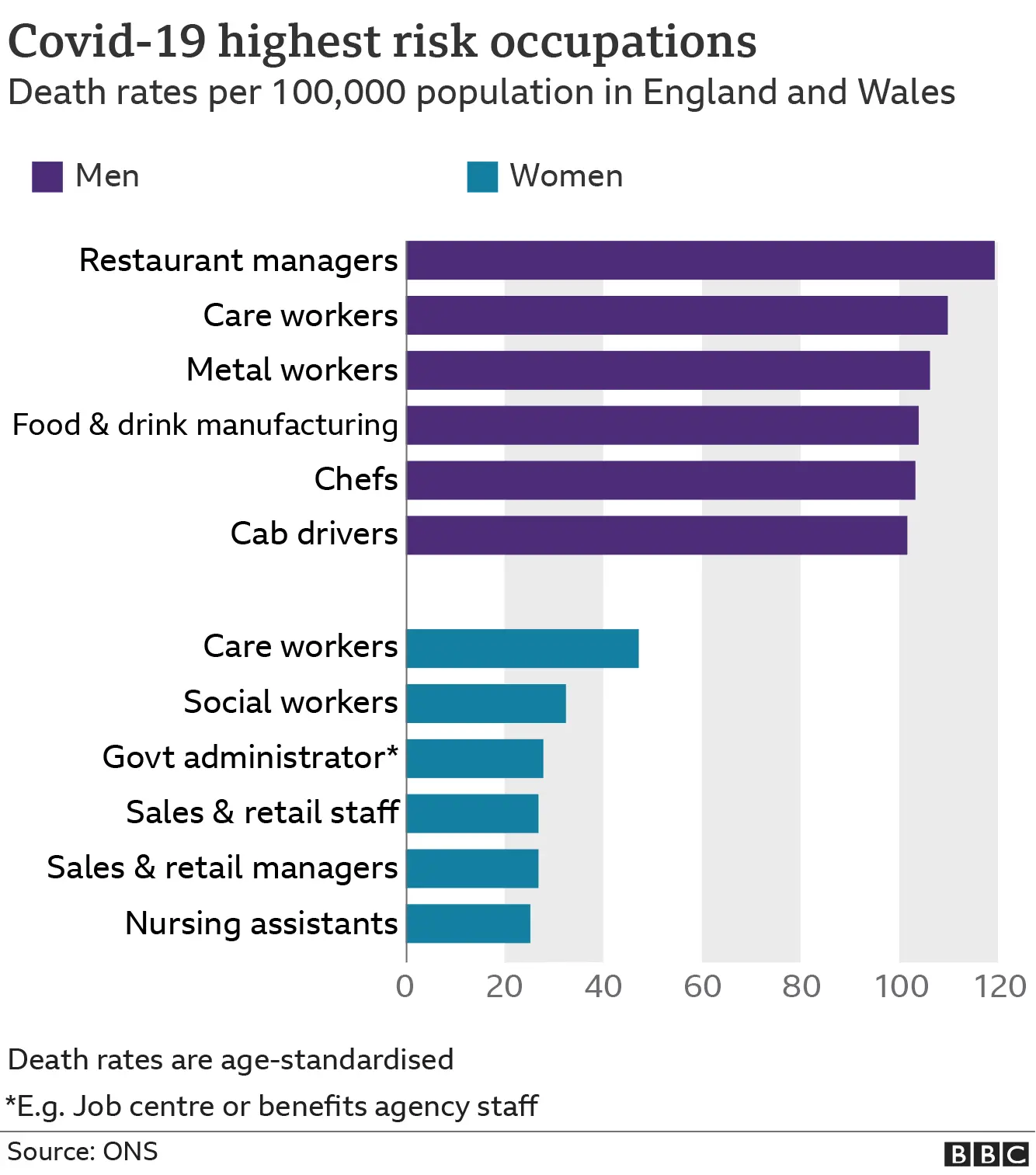

Restaurant staff, people working in factories and care workers had among the highest death rates, followed by taxi drivers and security guards.

Nurses were more than twice as likely as their peers to die of coronavirus.

Secondary school teachers may have been at slightly, but not measurably, higher risk than the average.

The ONS looked at death rates from coronavirus in England and Wales between 9 March and 28 December 2020.

It found 31 in every 100,000 working-age men and 17 in every 100,000 working-age women had died of Covid-19.

This equated to just under 8,000 deaths among 20-64-year-olds.

But care workers, security guards and people working in certain manufacturing roles died at more than three times the rate of their peers.

Two-thirds of deaths were among men.

As well as being more likely to be male, working-age people who died of Covid last year had other things in common: they were much more likely to work in jobs where they were either regularly exposed to known Covid cases or working in close proximity with other people more generally.

Many of the highest-risk jobs were also relatively low paid and may be more likely to be casual or insecure, without sick pay, including hospitality, care work and taxi driving.

Among teachers, there were 18 deaths per 100,000 among men and 10 per 100,000 among women.

Breaking that down by role, secondary school teachers appear to have a very slightly elevated risk at 39 deaths per 100,000 people in men and 21 per 100,000 in women.

Per 100,000 men aged 20-64, 31 died in the population as a whole compared with:

- 119 restaurant and catering staff per 100,000

- 110 care workers

- 106 metal-working machine operatives

- 101 taxi drivers

- 100 security guards

- 79 nurses

Per 100,000 women aged 20-64, 17 died in the population as a whole compared with:

- 47 care workers per 100,000

- 32 social workers

- 27 sales or retail assistants

- 25 nurses

- 22 cleaners

- 21 secondary education teaching professionals

These are illustrative examples, not an exhaustive league table.

The ONS calculated the rate by dividing the number of deaths by the number of workers in each job role.

Because the numbers for secondary teachers were comparatively small - 52 deaths in total - it's difficult to be certain about their exact risk, but any increase there might be compared with the general population was not considered statistically significant.

However, while teachers were not at higher risk than the average, they did appear to be at higher risk than some other professional job roles, which have seen very few or no deaths.

The ONS excluded from its analysis any occupation that had seen fewer than 10 deaths, and the average death rate for the whole population masks this variation.

The study also covers periods where there were limited numbers of children attending school.

But the figures do tell us teachers didn't have an elevated risk of the magnitude faced by health and care staff and by lower-paid manual and service workers.

Other groups of staff studied with higher death rates, including hospitality and some factory and construction workers, also had their usual work paused for similar chunks of that period.

While these figures tell us the death rates in each occupation group, they do not tell us the jobs are themselves causing more infections.

The ONS looked at age and sex but did not adjust for ethnicity, health or socioeconomic status which might influence an individual's risk.

ONS analyst Ben Humberstone said: "As the pandemic has progressed, we have learnt more about the disease and the communities it impacts most. There are a complex combination of factors that influence the risk of death; from your age and your ethnicity, where you live and who you live with, to pre-existing health conditions.

"Our findings do not prove that the rates of death involving COVID-19 are caused by differences in occupational exposure," he added.

This also just refers to deaths, not infections which may result in serious illness.

Some earlier ONS data suggested certain types of teacher may have an increased risk of catching coronavirus, although again the body did not consider this to be statistically significant.

Director of policy for the Association of School and College Leaders teachers' union, Julie McCulloch, said: "When trying to understand rates of coronavirus-related deaths, there are likely to be many complex factors and we need to be careful not to jump to conclusions about the relative risks of different workplaces.

"What we do know is that, when schools are fully open, education staff are asked to work in environments that are inherently busy and crowded. In order to give them reassurance, and to minimise the disruption to education, it is vital that they are prioritised for vaccination as soon as possible."

Whether teachers should be prioritised for vaccines has been a matter of debate.

At the moment the programme is being rolled out based on what will save the most lives and prevent the most severe illness.

After the oldest age groups, people with health conditions and frontline staff who are regularly exposed to the virus, the government will have to publish a new raft of priorities.

Vaccines minister Nadim Zahawi has indicated more people could be prioritised on the basis of their job role, including teachers, shop workers and police officers.