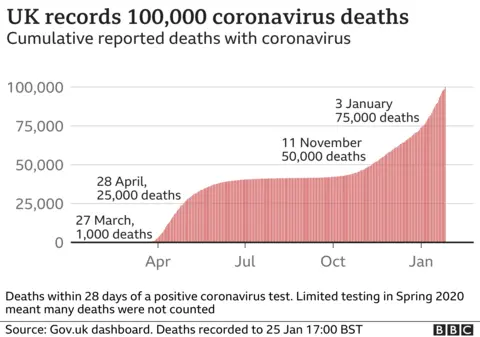

Covid deaths: Why is the UK's death toll so bad?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore than 100,000 people in the UK have died from a virus, that, this time last year, felt like a far-off foreign threat. How did we come to be one of the countries with the worst death tolls?

There is no quick answer to that question, and there is sure to be a long and detailed public inquiry once the pandemic is over. But there are plenty of clues that, when pieced together, help build a picture of why the UK has reached this devastating number.

Some will point a finger at the government - its decision to lock-down later than much of western Europe, the stuttering start to its test-and-trace network and the lack of protection afforded to care home residents.

Others will spotlight deeper rooted problems with British society - its poor state of public health, with high levels of obesity, for example.

Others, still, will note that some of the UK's great strengths - its position as a vibrant hub for international air travel, its ethnically diverse and densely-packed urban populations - exposed its vulnerability to a virus that spreads effortlessly between people.

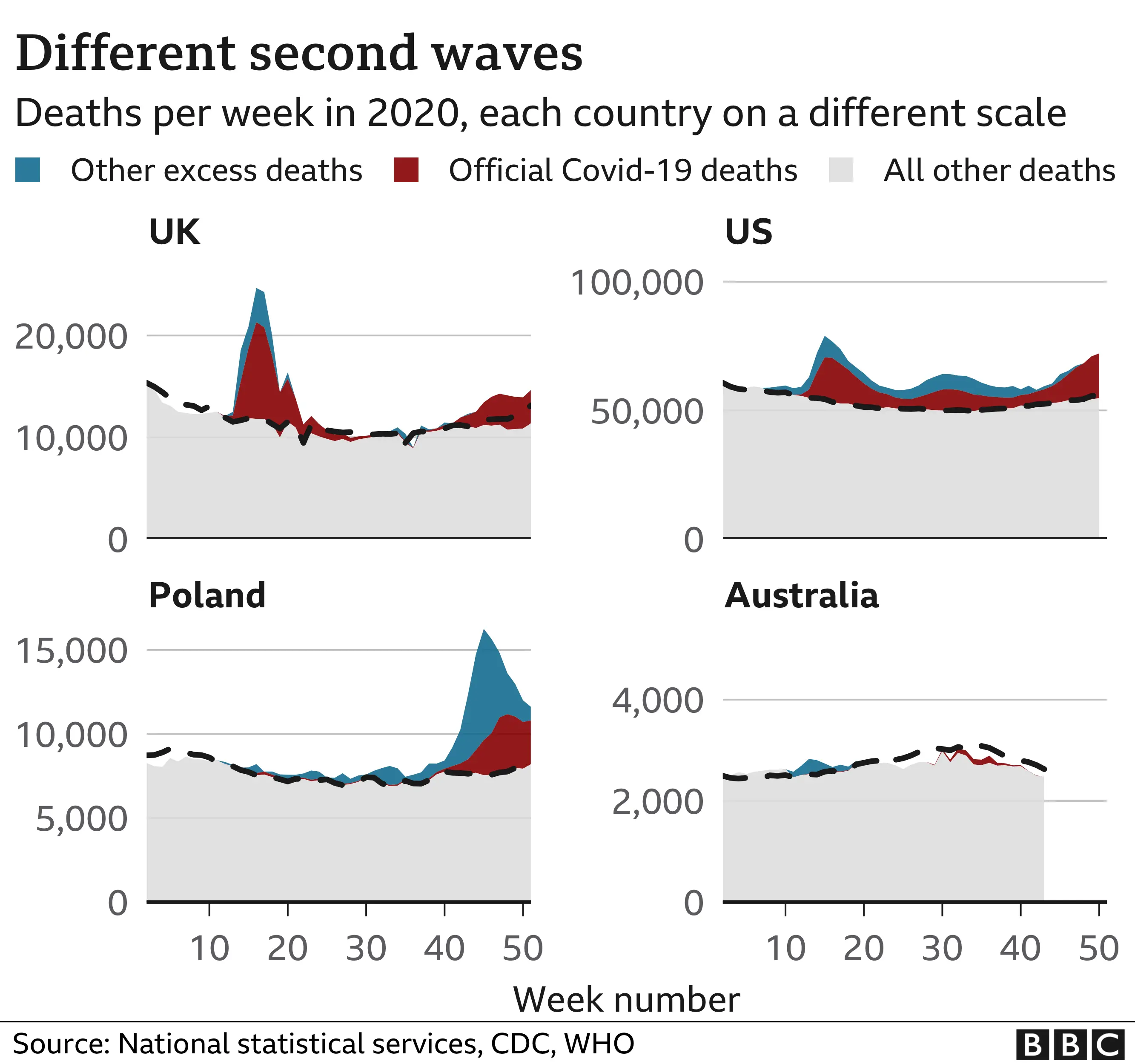

BBC

BBCIn some people's eyes, the UK's island status might have helped it. New Zealand, Australia and Taiwan managed to stop the virus getting a foothold and deaths have been kept to a minimum - Australia has seen fewer deaths throughout the pandemic than the UK is recording every day on average.

All introduced strict border restrictions immediately and lockdowns to contain the virus before it had spread. The UK did not. It was not until June that quarantine rules were introduced for all arrivals and even then travel corridors were soon set up, relaxing the rules for travellers from certain countries. Only this month were these scrapped.

BBC

BBCProf Devi Sridhar, an expert in public health from Edinburgh University, is one of those who has been critical of the approach the UK has taken from the start.

She says the UK, like much of Europe, was "complacent" about the threat of infectious disease - choosing to treat the new coronavirus "like flu" and allowing it to spread, while talking about the desire to achieve herd immunity.

This all changed in late March, when a full lockdown eventually came. But there was a crucial delay of a week which is estimated to have cost more than 20,000 lives, according to government modeller Prof Neil Ferguson, because of how quickly infection rates were doubling at that point.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis, of course, is said with the benefit of hindsight. Government modellers themselves acknowledge the data was "really quite poor" making it difficult to make a decision that would have significant repercussions. It is a point acknowledged by Prof Chris Whitty, the UK's chief medical adviser. Speaking in the summer he said there had been "very limited information" in early March.

By then, the virus was ripping through care homes. Around 30% of deaths in the first wave happened in care homes; 40% if you include care home residents who died in hospital.

Those at the heart of government acknowledge mistakes were made. UK chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance said recently: "The lesson is go earlier than you think you want to, go harder than you think you want to, and go a bit broader than you think you want to in terms of applying the restrictions."

BBC

BBCBy May, restrictions were beginning to be eased. But was this too soon?

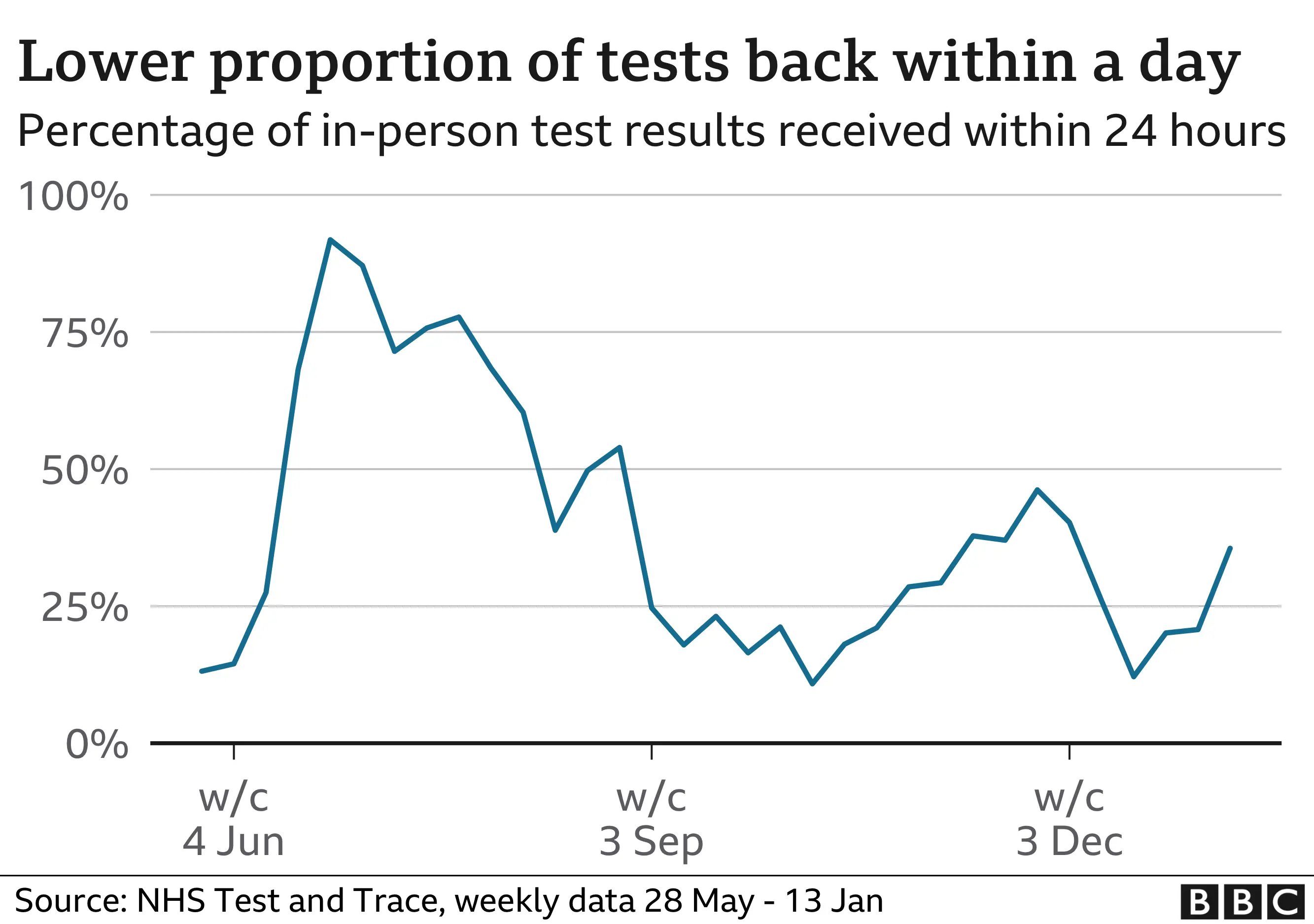

The government seized on the relative lull to focus on building what the prime minister promised would be a "world-beating" test-and-trace system. The idea was that new outbreaks could be nipped in the bud, with comprehensive tracking by a centralised team of tracers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe mere fact this had to be done some months after the virus had struck, illustrates another factor behind the high number of deaths - the UK was simply not prepared for a pandemic of this nature in the way some Asian nations had been. Countries such as South Korea and Taiwan had established test-and-trace systems in place that were ready to be activated.

The UK had a chance to bed in its system in the summer but it was riven with teething problems, with tracers struggling to reach many contacts and the testing capacity slowing down as demand rose.

Low levels of infection over the summer had created a false sense of security.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDesperate to boost the economy, the government launched the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, offering people discounted meals out during August. To what extent it contributed to the rise in the autumn is much argued about but certainly some doctors blame it in part for an increase in patients seen.

The truth is the virus never went away. Testing in the summer showed even at the lowest levels there were still around 500 cases a day being diagnosed - and random testing in the population subsequently showed the true level may have been twice that.

BBC

BBCIn late August around 1,000 people a day were testing positive. By mid-September that had trebled and from there it rose five-fold to 15,000 by mid October. The numbers testing positive have never returned below 10,000 a day on average since.

Another decision that has been heavily criticised was the refusal of ministers to introduce a short two-week lockdown, or "circuit breaker", in September - despite their advisers on Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) recommending such a step. The argument was it would have set the spread of the virus back by at least a month, giving test and trace time to regroup.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWales, however, did introduce its own "fire-breaker" - a 17-day lockdown in October. It got infection rates down, but as soon as it was lifted they rebounded. This is, of course, why lockdowns have been criticised.

Edinburgh University infectious diseases expert Prof Mark Woolhouse, one of the modellers who feeds data into Sage, is on the record in the autumn questioning the logic of them for this very reason. It remains up for debate how effective a circuit-breaker would actually have been.

This after all is the time of year when respiratory illnesses start to increase. Schools had returned as had university students, creating new environments for the novel coronavirus to spread.

When a lockdown was eventually introduced in England in November it was to last four weeks, with Sage members lamenting the delay. "The absence of a decision is a decision in itself," says Wellcome Trust director Sir Jeremy Farrar.

But even before that lockdown was lifted cases had started going up in the south-east of England. Within weeks it became clear what was happening. The virus had mutated and a new faster-spreading variant was on the rise.

By mid-December the clamour for lockdown was growing again, but the plan for a Christmas relaxation of restrictions had already been announced. In every nation of the UK, ministers waited.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the start of 2021, with hospital admissions rising rapidly, the UK's four chief medical officers intervened, issuing a joint statement warning the NHS was at "material risk" of being overwhelmed. Within hours the UK was back in lockdown.

What has struck some is just how similar the mistakes have been in terms of locking down late.

"It will take years to unpick why Covid has gone so badly in the UK," says University College London infectious diseases expert Dr Neil Stone. "But the failure to learn from wave one stands out."

Deeper causes

But it must also be recognised that there are factors outside the control of the government - certainly in terms of its pandemic response - that have contributed to the high number of deaths.

One of the reasons the virus was able to take a hold and spread so quickly was because of geography and the fact the UK - and London in particular - is a global hub. Genetic analysis has shown the virus was brought into the UK on at least 1,300 separate occasions, mainly from France, Spain and Italy, by the end of March.

It was here before we knew it. That's not something Australia or New Zealand had to deal with on such a scale.

Density of population is also a factor. The UK is among the 10 most densely populated big nations - those with populations of more than 20 million. What is more, our cities are more inter-connected than they are in many places.

It meant the virus was able to seed everywhere quite quickly. Contrast this with Italy which saw the vast majority of cases in the north of the country in the first wave.

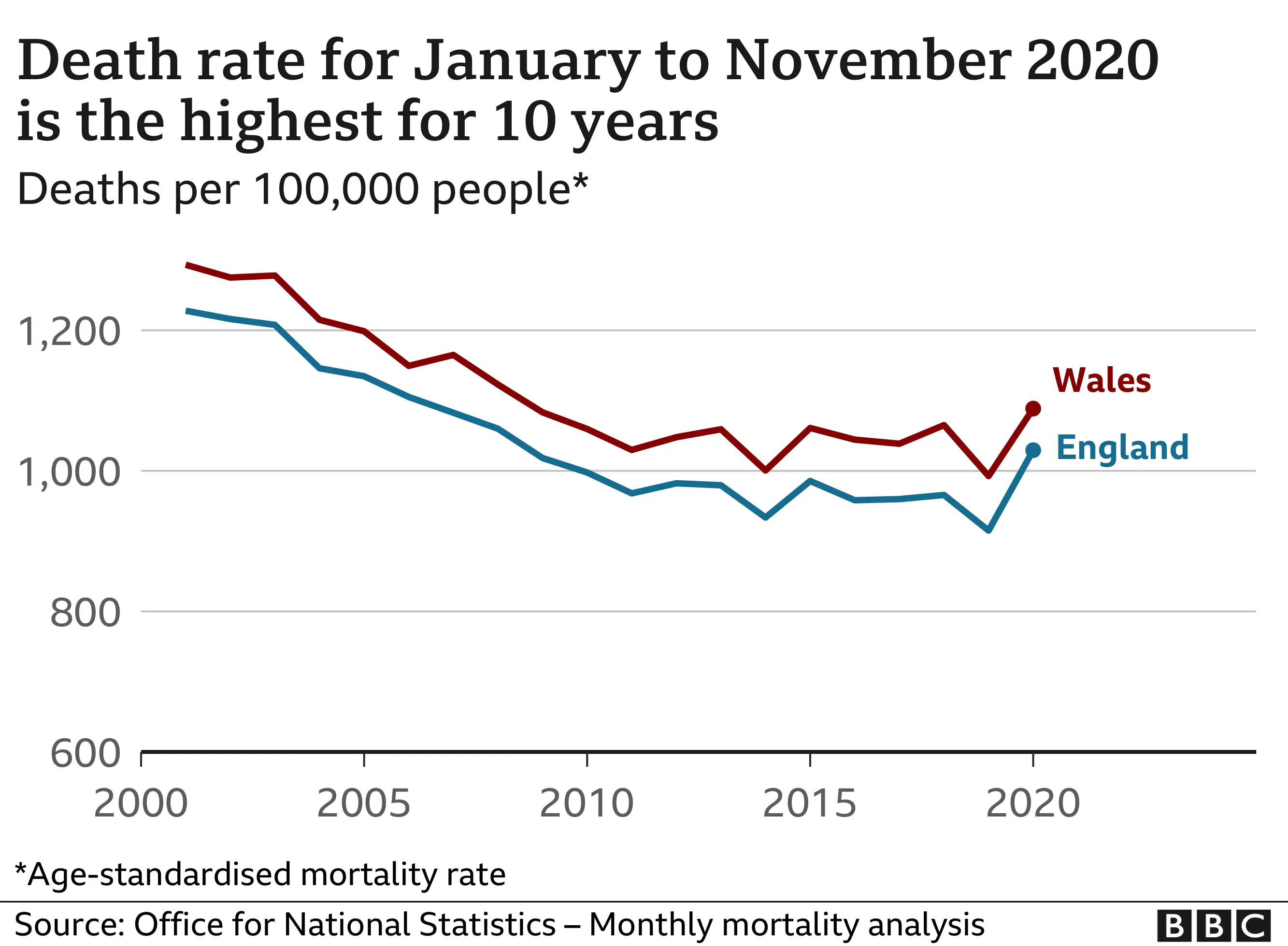

The ageing population also needs to be taken into account. Once you do this, and adjust for the size of the population - known as age-standardised mortality - deaths have risen, but not by as much as some of the headline figures suggest.

BBC

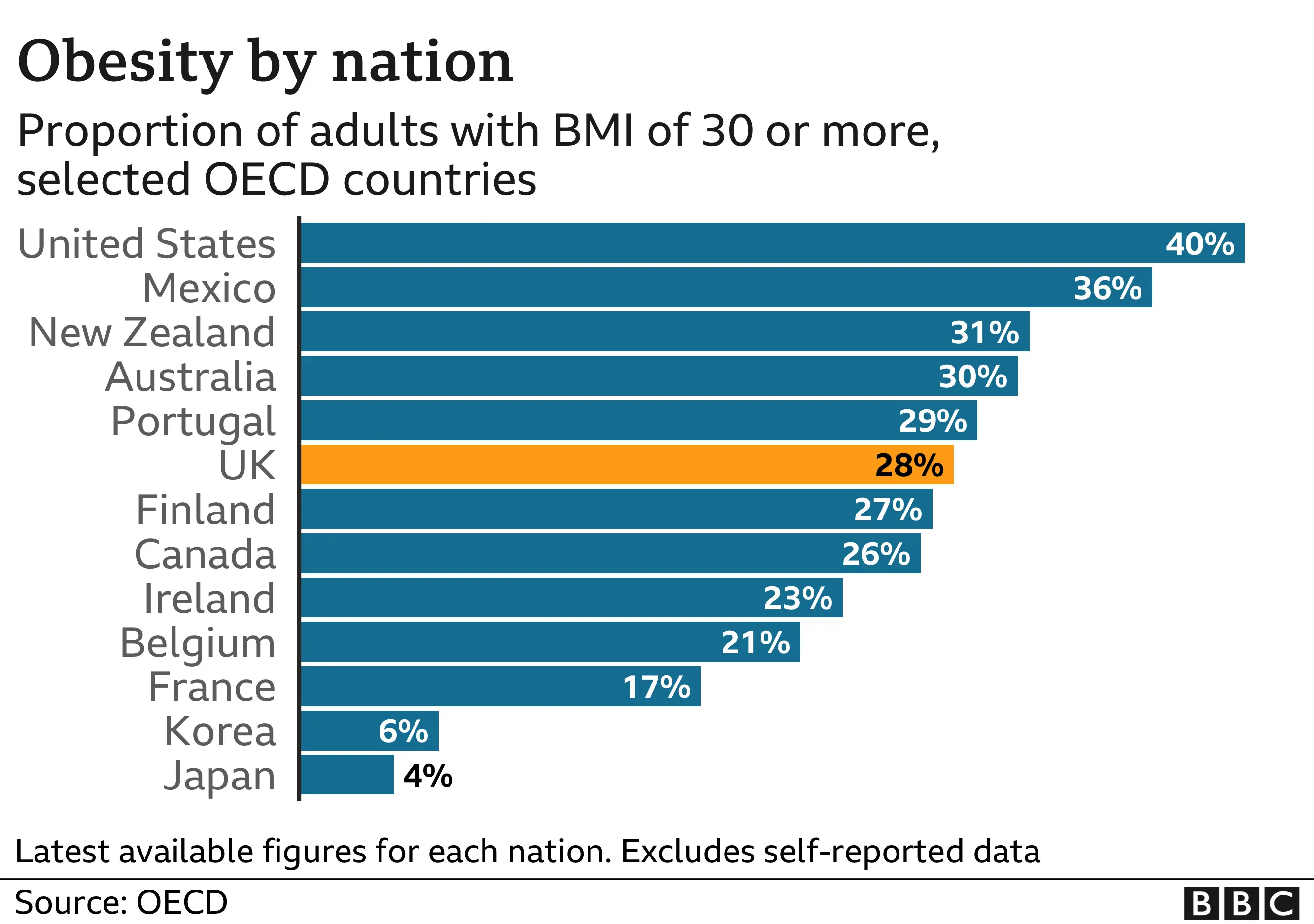

BBCThe health of the nation has also been a factor. The UK has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world. And obesity increases the risk of hospitalisation and death, according to Public Health England. One study found the risk of death was almost double for those who are severely obese.

BBC

BBCConditions such as diabetes, kidney disease and respiratory problems also increase the risk - a fifth of Covid deaths have listed diabetes on the death certificate.

Again the UK has relatively high rates of these illnesses.

But many have argued that these high levels of ill-health have been compounded by the levels of inequality in the UK.

Levels of ill health and life expectancy have always been worst in the poorest areas, but the pandemic certainly seems to have exacerbated this.

BBC

BBC- LOCKDOWN LOOK-UP: The rules in your area

- TRAVEL: What are the UK's rules?

- SUPPORT BUBBLES: What are they and who can be in yours?

BBC

BBCOffice for National Statistics data shows mortality rates have been twice as high in deprived areas as they have been in wealthy areas. The Health Foundation is carrying out its own inquiry into the issue, arguing the Covid death toll needs to be seen through the "lens" of inequality to fully understand it.

It is something that has also been raised by Prof Michael Marmot, one of the country's leading experts on health inequalities. "The UK's dismal record is telling us something important about our society."

All photographs subject to copyright

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by bereavement, here is a list of organisations that may be able to help.