Mass testing: Can it save us from another lockdown?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMass testing is being touted as a way of getting us much closer to a normal life and even of avoiding lockdowns in the future.

Testing everyone - even those without symptoms - can be an incredibly powerful tool for rooting out the virus.

Boris Johnson has promised a "massive expansion" in such testing in the UK and Liverpool is the first city to trial it.

But questions have been asked about the current tests and the overall strategy. So, what can mass testing realistically achieve?

Sir John Bell, from the University of Oxford, is the government's adviser on life sciences and he says it "may well keep us out of trouble" but it is "very important we don't over-hype".

The promise of mass testing

Mass testing is similar to cancer screening - you take healthy people, test them and then you act early if there are any problems.

But instead of finding the hidden cancer, you find people who have the virus who may not know it yet.

The hope is this can be used to stamp out an outbreak, by getting everyone who tests positive to isolate, without turning to strict restrictions.

China has done this on multiple occasions by mass testing everyone in a city after a cluster of cases was detected. Slovakia is attempting this across the entire country.

Reuters

ReutersThere are also more targeted ways of using mass testing:

- Regular, even daily, testing in a hospital or care home could prevent an outbreak among people who are at the highest risk of Covid-19

- And it could keep places where the virus can spread, like schools and universities, open

- Another option is a one-off test before being able to go to the cinema, theatre or a football match

"These tests will come online, they will be good and they are what we need, but we need to understand how well they work and not over-promise on them," said Prof Jon Deeks, from the University of Birmingham.

Mass testing technology

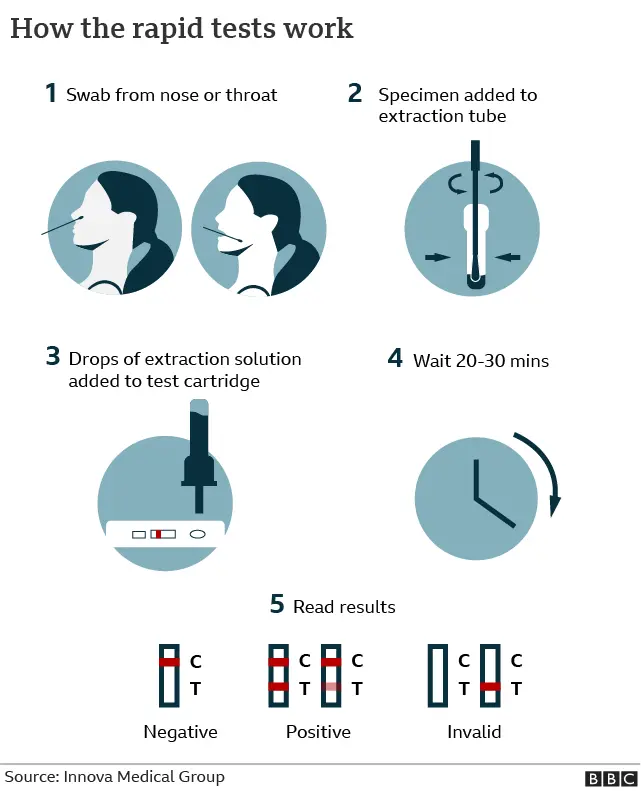

One piece of kit has allowed the idea of mass testing to happen. It is called a lateral flow test which rapidly detects parts of the coronavirus itself.

These are similar to pregnancy tests and are easy, cheap and fast.

Fluid from a nasal swab or saliva goes on one end, then a marking appears if you are positive. No scientists or laboratories are required.

There is another technology called LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification), which is regularly rolled into discussions on mass or rapid testing.

But swabs still need to be collected, sent to a laboratory, handled by trained staff and the results sent back out. So LAMP only improves one step in the current testing process.

Speed and simplicity vs accuracy

The rapid tests are not as accurate as the current, lab-based PCR tests that hunt for fragments of the virus' genetic code.

"They are not perfect, if you pretend they are 'PCR in a stick' we'll end up with all kinds of trouble," Sir John told the BBC.

The full results on the effectiveness of the rapid tests have not been released.

Sir John, who is advising the government, said between one-in-500 and one-in-1,000 people would be told they had the virus, when they did not.

This is an important figure because "false positives" can become a problem when regularly testing large numbers of people. Test 60 million people twice a week and it adds up to nearly a quarter of a million people incorrectly told to isolate every week.

He also said the tests correctly identify 90% of infected people if they had high levels of the virus in their body, but only 60-70% overall. Which figure is more useful is debated.

"Will there be people who are potentially infectious who test negative? Yes," said Sir John. "I suspect that will happen and it won't happen very often."

Positive or 'infectious'?

The criticism of the current PCR tests is they are so good at finding the virus they give positive results long after the patient has recovered and is no longer able to spread Covid.

The rapid or lateral flow tests have the opposite problem. They need very high levels of the virus in order to give a positive result.

Some, including the prime minister, argue this allows you to focus on people who are "infectious".

Prof Deeks argues this may miss crucial people in the early stage of the infection when levels of the virus are lower and the rapid tests are "not proven" as a test of infectiousness.

"I don't think the data is there, we're just rushing too fast with this, we don't know how well these tests work in people without symptoms," he told the BBC.

It may mean people need testing every couple of days in order to catch an early-stage infection, but more testing means more false positives.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAre these tests going to be useful in practice?

Sir John says even a test that found the virus in only half of people without symptoms would still be useful.

"Then every other person [who tests positive] is somebody you have diagnosed that you would never have seen before," he says.

He said to stop one person catching the virus you have to:

- lockdown 1,000 people for a day, "that's why people hate it, it is so inefficient"

- isolate 70 people for a day based on an app notification

- isolate five people for a day who have a positive PCR test and symptoms

- isolate two to three people for a day who test positive after a lateral flow test

The figures come from a soon-to-be published analysis by Prof Tim Peto at Oxford.

The downsides of mass testing

Any form of mass screening or testing needs to balance harm and benefit. Some doctors even argue the well-established breast cancer screening programme does more harm than good.

"All tests can do harm because of the errors and when we screen we can end up with a lot of errors," said Prof Deeks.

He said telling people they had the virus when they did not would force people to isolate unnecessarily.

And people may take more risky behaviour if they have "false reassurance" from an incorrect negative test result, he said.

People might not even take the test

It is a mistake to think a test alone, even a mythical perfect one, could halt the pandemic.

A "critical barrier" to the success of mass testing is the number of people who agree to be tested and then isolate if they are positive, the government's scientific advisory group for emergencies (Sage) has warned.

It says less than 30% of people come forward for testing or fully isolate in the current test and trace system.

"They're not staying at home, possibly because they can't afford to and will lose their job," said Dr Alexander Edwards, from the University of Reading.

"Unless we support people to isolate, they are never going to stop carrying on with their lives and inadvertently passing on the virus."

There is also a danger people will "game the system" if we reach the point where people do their own tests before getting into events.

So can it prevent another lockdown?

Sir John Bell told the BBC: "I'd be a bold person to say yes, but having said that besides a vaccine we don't have many other options, it's worth a crack to see if it might.

"There is a possibility it may be the get out of jail card that we need, but it's early days".

Prof Deeks said: "There's no doubt they are going to help us at some point, but we need to slow down the pace and evaluate them better."

Follow James on Twitter