Coronavirus: Last throw of dice before the really tough call

Reuters

ReutersThe disconnect between scientists and ministers in England could not be more stark.

On Monday, the government's two most senior pandemic advisers - Prof Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance - set out the scale of the problem, raising the prospect of 50,000 cases a day by October.

On Tuesday, ministers provided their answer - closing pubs early, asking people to work from home and making face coverings mandatory in a few more situations. But that was about it.

In Northern Ireland and Scotland, they went further, banning visits to other people's homes. But even that fell short of the mini-lockdowns and "circuit breaks" floated last week.

Is the public tiring of the fight?

Clearly, there need to be trade-offs between containing the spread of the virus and minimising the impact to society.

But there is more to the past two days than that.

There is a recognition within government the public is tiring of the battle against coronavirus.

Estimates suggest only one in five people is self-isolating fully when asked.

And you need only to listen to government adviser Prof Robert Dingwall to realise the problem ministers are facing.

Last week, he warned the public was "just going through the motions" and had become "comfortable" with the idea that thousands would die just as thousands died with flu each year.

And this is the context in which Prof Whitty and Sir Patrick took to the screens in Monday.

The decision to present the 50,000-cases scenario was discussed carefully in advance I understand.

It was based on cases doubling every week from now until the middle of next month. This was happening at one point at the end of August and start of September.

But it is far from a given that it will continue - in fact even now the trajectory looks to be below that.

They could have referenced the trends Spain and France were on - two countries they mentioned in other parts of the briefing. But they didn't. If they had, this is what it would have looked like.

Sir Patrick did point out the 50,000 figure was not a prediction. But it was used in the knowledge it would grab the headlines.

Why? One person close to the decision-making told me it was about influencing behaviour - to try to persuade the public to redouble its efforts.

That much was clear from Prof Whitty's plea for people to think of others. If anyone increased their own risk of exposure, they also "increase the risk of everyone" around them, he said.

With the numbers of hospital admissions and deaths still low, there is a window of opportunity before more difficult decisions have to be taken.

And that is why the restrictions ministers introduced are somewhat more limited than the scientists' warning might have suggested was needed.

Is a rise in cases inevitable?

Even if the public does take more care - and the fear is the large proportion at minimal risk will not, as taking steps such as self-isolating for 14 days on the basis of close contact with an infected individual can cost people income - it remains doubtful the rise in cases will be halted.

That is because the virus is stealthy. People are infectious before symptoms develop - and some remain asymptomatic. On top of that we are entering the time of year when respiratory illnesses circulate more easily.

Many experts have questioned whether the 50,000-cases-a-day figure will be reached by mid-October - called implausible by some - but it would still be a big surprise if infection rates do not continue to gradually climb.

Prof Paul Hunter, from the University of East Anglia, says it is now "almost certain" there will be an increase in the next two to three months.

He wants to see more focus on protecting the most vulnerable. And that is likely to happen soon.

But the government will still have a big decision to make if it is determined to reduce the number of cases, which the prime minister suggested was its goal.

A full lockdown remains highly unlikely. But more significant steps, such as closing hospitality venues and leisure facilities and curbing everyday activities, from playing sport to travelling around the country, remain options.

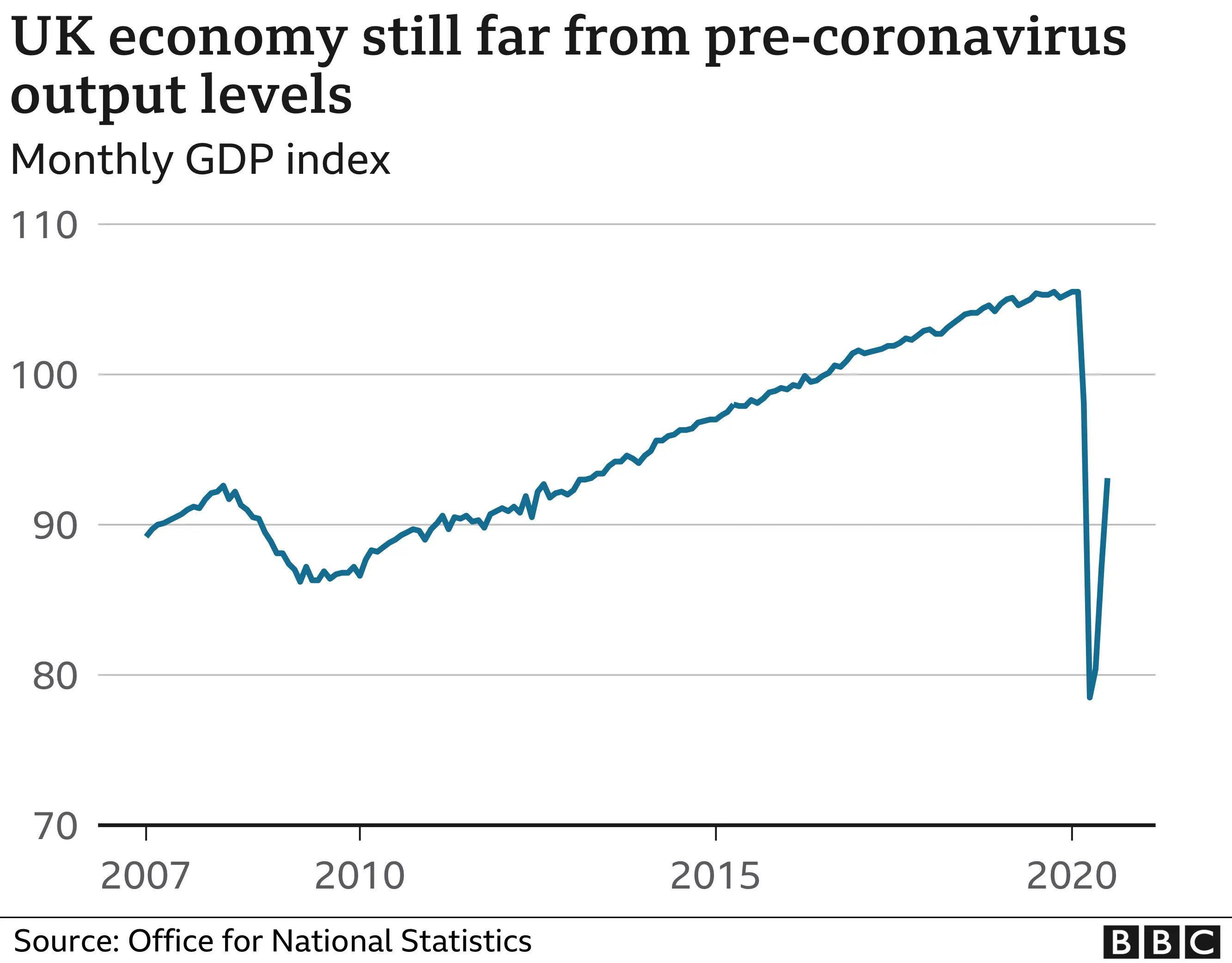

In the end it will come down to how far the government is prepared to go to contain the virus. How much economic pain and disruption and damage to society and the wider health and wellbeing of individuals is worth the lives at risk?

That, unfortunately, is the horrible dilemma likely to have to be faced. The really tough calls are still to come.

Follow Nick on Twitter