Coronavirus: Are mutations making it more infectious?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe coronavirus that is now threatening the world is subtly different from the one that first emerged in China.

Sars-Cov-2, the official name of the virus that causes the disease Covid-19, and continues to blaze a path of destruction across the globe, is mutating.

But, while scientists have spotted thousands of mutations, or changes to the virus's genetic material, only one has so far been singled out as possibly altering its behaviour.

The crucial questions about this mutation are: does this make the virus more infectious - or lethal - in humans? And could it pose a threat to the success of a future vaccine?

This coronavirus is actually changing very slowly compared with a virus like flu. With relatively low levels of natural immunity in the population, no vaccine and few effective treatments, there's no pressure on it to adapt. So far, it's doing a good job of keeping itself in circulation as it is.

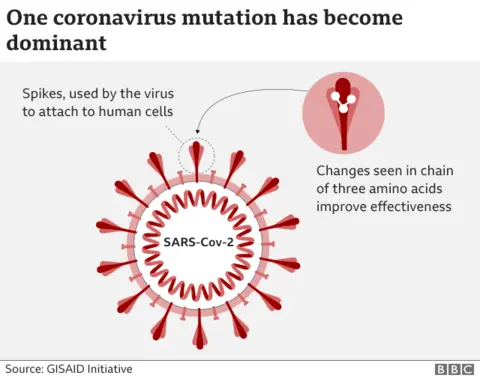

The notable mutation - named D614G and situated within the protein making up the virus's "spike" it uses to break into our cells - appeared sometime after the initial Wuhan outbreak, probably in Italy. It is now seen in as many as 97% of samples around the world.

Evolutionary edge

The question is whether this dominance is the mutation giving the virus some advantage, or whether it's just by chance.

Viruses don't have a grand plan. They mutate constantly and while some changes will help a virus reproduce, some may hinder it. Others are simply neutral. They're a "by-product of the virus replicating," says Dr Lucy van Dorp, of University College London. They "hitch-hike" on the virus without changing its behaviour.

The mutation that has emerged could have become very widespread just because it happened early in the outbreak and spread - something known as the "founder effect". This is what Dr van Dorp and her team believe is the likely explanation for the mutation being so common. But this is increasingly controversial.

A growing number - perhaps the majority - of virologists now believe, as Dr Thushan de Silva, at the University of Sheffield, explains, there is enough data to say this version of the virus has a "selective advantage" - an evolutionary edge - over the earlier version.

Though there is still not enough evidence to say "it's more transmissible" in people, he says, he's sure it's "not neutral".

When studied in laboratory conditions, the mutated virus was better at entering human cells than those without the variation, say professors Hyeryun Choe and Michael Farzan, at Scripps University in Florida. Changes to the spike protein the virus uses to latch on to human cells seem to allow it to "stick together better and function more efficiently".

But that's where they drew the line.

Prof Farzan said the spike proteins of these viruses were different in a way that was "consistent with, but not proving, greater transmissibility".

Lab result proof

At the New York Genome Center and New York University, Prof Neville Sanjana, who normally spends his time working on gene-editing technology Crispr, has gone one step further.

His team edited a virus so that it had this alteration to the spike protein and pitted it against a real Sars-CoV-2 virus from the early Wuhan outbreak, without the mutation, in human tissue cells. The results, he believes, prove the mutated virus is more transmissible than the original version, at least in the lab.

Dr van Dorp points out "it is unclear" how representative they are of transmission in real patients. But Prof Farzan says these "marked biological differences" were "substantial enough to tilt the evidence somewhat" in favour of the idea that the mutation is making the virus better at spreading.

- BUBBLES: How do they work and who can be in yours?

- SYMPTOMS: What are they and how to guard against them?

- FACE MASKS: When should you wear one?

- TESTING: Who can get a test and how?

Outside a Petri dish, there is some indirect evidence this mutation makes coronavirus more transmissible in humans. Two studies have suggested patients with this mutated virus have larger amounts of the virus in their swab samples. That might suggest they were more infectious to others.

They didn't find evidence that those people became sicker or stayed in hospital for longer, though.

In general, being more transmissible doesn't mean a virus is more lethal - in fact the opposite is often true. There's no evidence this coronavirus has mutated to make patients more or less sick.

But even when it comes to transmissibility, viral load is only an indication of how well the virus is spreading within a single person. It doesn't necessarily explain how good it is at infecting others. The "gold standard" of research - a controlled trial - hasn't yet been carried out. That might involve, for example, infecting animals with either one or the other variant of the virus to see which spreads more in a population.

One of the studies' leads, Prof Bette Korber, at Los Alamos National Laboratory in the US, said there was not a consensus, but the idea the mutation increased patients' viral load was "getting less controversial as more data accrues".

The mutation is the pandemic

When it comes to looking at the population as a whole, it's difficult to observe the virus becoming more (or less) infectious. Its course has been drastically altered by interventions, including lockdowns.

But Prof Korber says the fact the variant now appears to be dominant everywhere, including in China, indicates it may have become better at spreading between people than the original version. Whenever the two versions were in circulation at the same time, the new variant took over.

In fact, the D614G variant is so dominant, it is now the pandemic. And it has been for some time - perhaps even since the start of the epidemic in places like the UK and the east coast of the US. So, while evidence is mounting that this mutation is not neutral, it doesn't necessarily change how we should think about the virus and its spread.

On a more reassuring note, most of the vaccines in development are based on a different region of the spike so this should not have an impact on their development. And there's some evidence the new form is just as sensitive to antibodies, which can protect you against an infection once you've had it - or been vaccinated against it.

But since the science of Covid-19 is so fast-moving, this is something all scientists - wherever they stand on the meaning of the current mutations - will be keen to keep an eye on.

Follow Rachel on Twitter

- BRITAIN'S CANCER CRISIS: How has cancer care been affected by Covid-19?

- DIET AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM How important is a healthy diet?