Coronavirus doctor's diary: 'We aren't diagnosing many cancers now'

John Wright

John Wright

Planned surgery has been cancelled at hospitals across the UK, leaving much work to be done once the Covid-19 emergency is over. But two colorectal surgeons at Bradford Royal Infirmary also believe that the surgical world will be permanently changed - as Dr John Wright discovers in his regular diary.

27 April 2020

Like a runner who has discovered halfway through her race that it has changed from a sprint to a marathon, the hospital is coming to terms with a new pace and is recalibrating its stamina.

Numbers of cases have started to fall, but there's no finishing line in sight.

And as we continue running, we have to look ahead to the future - we have to work out how we can resume normal business, looking after patients with cancer and heart disease, asthma and arthritis.

At present, half the hospital is empty, while the other half has become a Covid-19 Red Zone; in time it will contain two parallel universes, Covid and non-Covid.

Surgeons, who have concentrated on emergency operations since the start of the epidemic, will resume planned operations in the non-Covid universe. But until a reliable test is developed that can be used to confirm that a patient is Covid-negative, the assumption will have to be that they are Covid-positive, and this has some important consequences.

I spoke to two consultant colorectal surgeons, Sonia Lockwood and Frankie Mosley, about what has changed for them so far, and what they think will change in future.

They confirmed that all work except for emergency surgery and some cancer surgery has been put on hold. They also said that keyhole surgery has come to a halt, as evidence from China and some European countries suggests that open surgery is safer for operating theatre staff.

Front line diary

Prof John Wright, a medical doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio 4's The NHS Front Line

- Listen to the next episode at 11:00 on Tuesday 28 April, catch up with the previous episodes online, or download the podcast

- You can also read the previous online diary entry: A couple inseparable in sickness and in health

- Check out all the diary entries on the BBC Radio 4 website

It may now resume, in some cases, with the increased risk to medical staff being weighed against the risks to the patient of a longer stay in hospital, which is one of the consequences of open surgery.

But increased efforts will also be made to explore non-surgical options. Appendicitis provides a good example of this, Sonia says.

"We are looking to treat people conservatively, with antibiotics wherever we can. We're doing more complex scanning on patients to try and determine who will be suitable for that. So we're really avoiding operating on patients wherever possible."

And appendicitis also illustrates another point - people who really need treatment are not always coming to hospital.

"Where we would normally do appendectomies maybe once a day, maybe two or three a day, at first, after the lockdown, we didn't see any. But then, after a week or so, the patients that are coming in with appendicitis have come in with terrible appendicitis," Sonia says.

"They've waited at home until it's perforated, so what would have been a relatively straightforward illness and operation then becomes a much more significant illness and operation."

Normally, there would be a minimum of about 30 admissions coming through the hospital's surgical assessment unit every day but that went down to two or three, Sonia says.

John Wright

John Wright

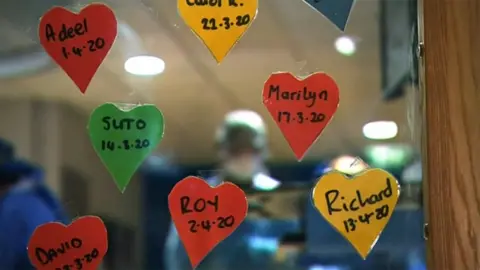

The surgeons are also dealing with fewer cancer patients.

In some cases this is because a calculation has been made that the risk of bringing them in is higher than the risking of waiting. But there is another factor too, Frankie says.

"We certainly, at the moment, aren't diagnosing many cancers at all. Our main modality for diagnosing them is endoscopy - colon endoscopy [a camera inserted into the body on the end of a tube] - and we've more or less ceased that activity," she says.

"We are investigating people - we're scanning them, so we'll pick up the most advanced cancers - but we're not diagnosing anywhere near the normal numbers. So we are just putting this work off for later."

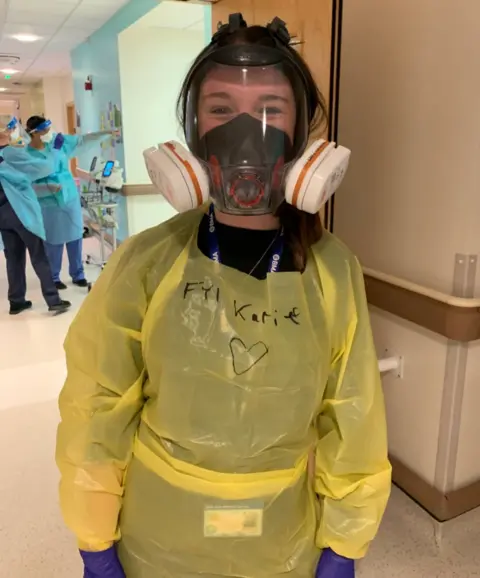

But operations carried out in full personal protective equipment (PPE), as they must be until there is a test for Covid-19, are time-consuming.

"What we may have been able to do six months ago, in a given day, we can only do half of that - and that's if we get all the theatres back, and all the ventilators back," Frankie says.

The same applies to diagnostic tests - X-rays, camera tests, endoscopy - everything will take longer because of safety procedures that have been put in place in for both patients and staff.

And this, combined with the fact that there will be a backlog of operations, will lead inevitably to more prioritisation, Sonia and Frankie believe.

At present, cancer surgery is a top priority, and for everyone else it's been first come first served, as Frankie puts it. In future they envisage pushing lower-priority operations down the queue.

What does that mean in the case of colorectal surgery?

"For us it will be some of people's haemorrhoid operations. They might have to put up with bleeding - it is inconvenient and unpleasant, but they might have to put up with it for a bit longer than they traditionally have had to," Frankie says.

Sonia adds that when it comes to general surgery, some hernia patients could be de-prioritised.

"While they've got lumps and bumps that are maybe uncomfortable and they've got some symptoms, most people have very mild symptoms," she says.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health

The remarkable drop off we've seen in hospital referrals, has been matched when it comes to A&E attendances. While we're worried about the patients who may not be coming to hospital when they need to, this also suggests that people who are using A&E have not always experienced an accident or an emergency.

"There are lots of people who use the NHS inappropriately, acknowledging that it's quicker to come to A&E and wait for hours than maybe wait for a GP appointment two weeks from now," Sonia says. "And I think the Covid crisis has actually highlighted that - that people are trying to bypass the system."

In an NHS which is struggling to meet ever increasing demand, we have an opportunity to reduce unnecessary hospital appointments - to do things differently. Patients have discovered the joys of seeing their consultant without leaving the comfort of their own homes, and remote or virtual consultations look like one of the big changes that are here to stay.

The success of our response to Covid-19 in hospitals across the UK has been down to a grassroots movement of doctors and nurses on the front line. They have been the ones who have taken control of the NHS, put their lives on the line and tamed the Covid dragon.

This has broken down a barrier between clinical and managerial staff in hospitals, Sonia says, and she looks forward to a continuation of open dialogue as we plan for the future.

In management theory, there's a classical model about change that describes how to unfreeze the existing system and then refreeze it in a new way of working. It's a neat concept but in reality this never happens. Until now. Covid-19 has defrosted the whole of the NHS, and we have to now work out what we want to keep and what we want to do differently.

Follow @docjohnwright on Twitter