Coronavirus: Does 20,000 hospital deaths milestone mean failure for UK?

PA Media

PA MediaThe first death linked to coronavirus in the UK was announced in early March. It was a woman in her 70s.

There have now been more than 20,000 fatalities since, according to the government's daily figures.

The tragic milestone is significant - at the outbreak's start, chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance said keeping the death toll to that figure would be "horrible" but a "good outcome" given the country's challenge.

The government had been warned that up to 500,000 people could die if the virus's spread was not stopped.

Does reaching this landmark mean the UK has failed to achieve its goals, and what happens from here?

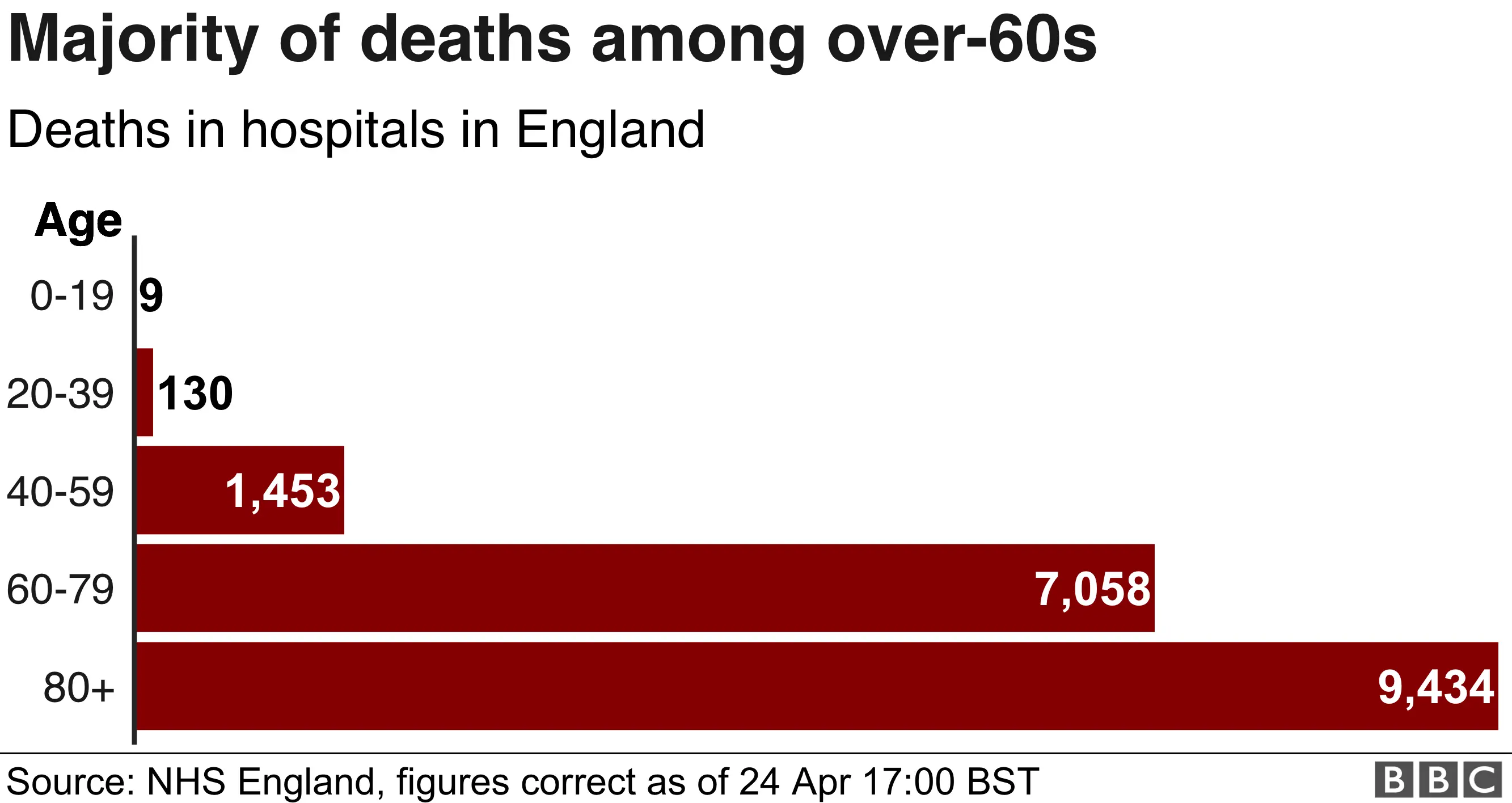

Most deaths have been among older people

Coronavirus is a mild illness for most - it is estimated only about one in 20 cases that develop symptoms need hospital treatment.

There have been cases involving health workers, younger adults and children, but the virus has - as expected - preyed largely on older people, particularly the frail and those with existing health problems.

Data from hospitals in England last week showed more than nine in 10 deaths have been in the over-60s and there is a similar picture in the rest of the UK.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has also looked at the deaths, analysing what proportion had pre-existing health conditions.

Again, more than nine out of 10 did, with the average between two and three. Heart disease was the most common.

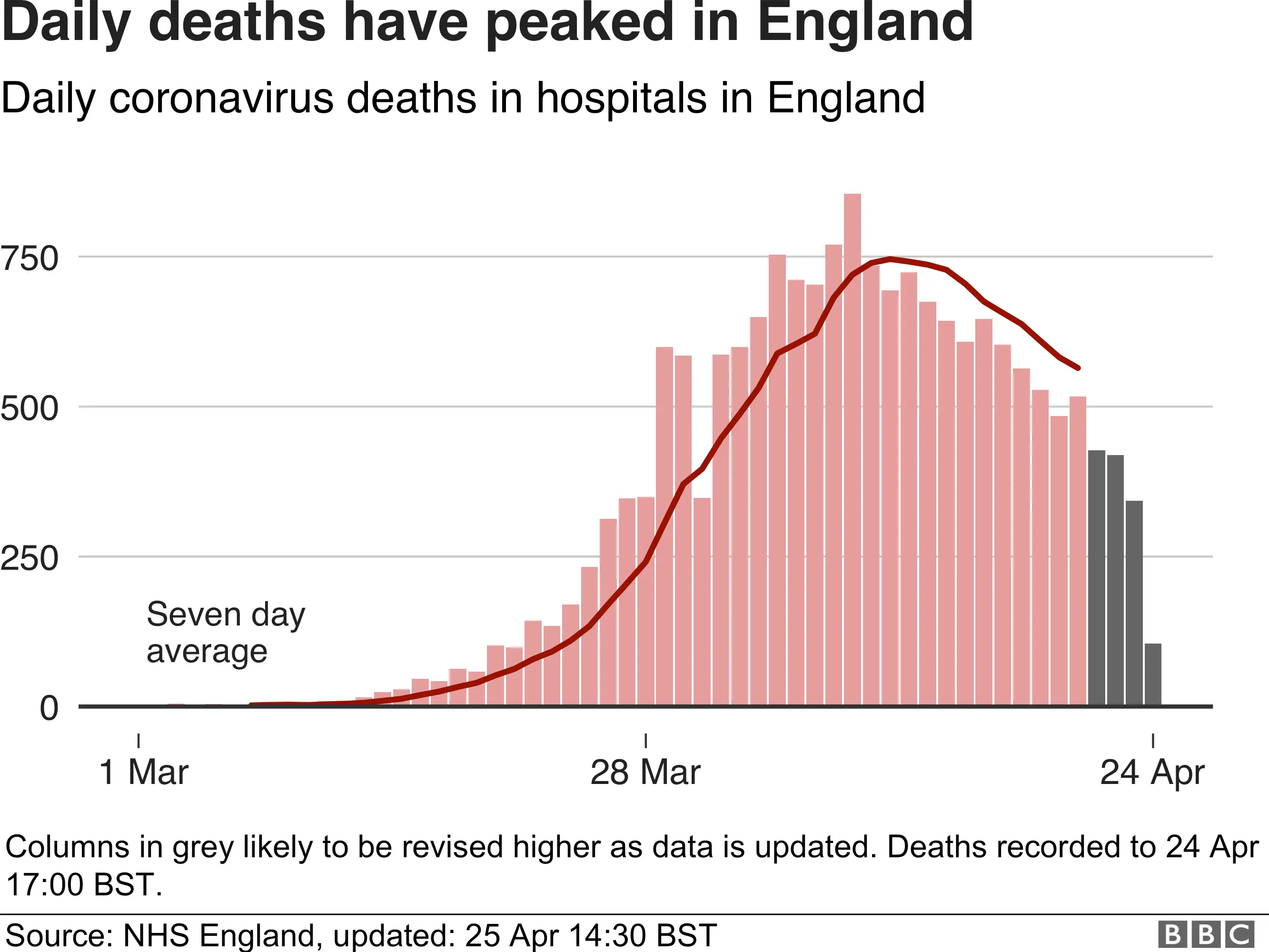

Hospital deaths may have peaked

The government figures are deaths that have happened in hospitals. They do not take into account fatalities in care homes or the community - so in reality the 20,000 mark would have been passed before now.

But it is still an important measure - as these deaths are the ones being monitored in terms of judging when the lockdown should be lifted (one of the key five tests is a sustained fall in deaths).

The good news from that point of view is that the numbers seem to be coming down. When you look at the deaths by the date they happened, it appears that the peak happened in the first half of April - in England at least. Comparable data is not available in the rest of the UK.

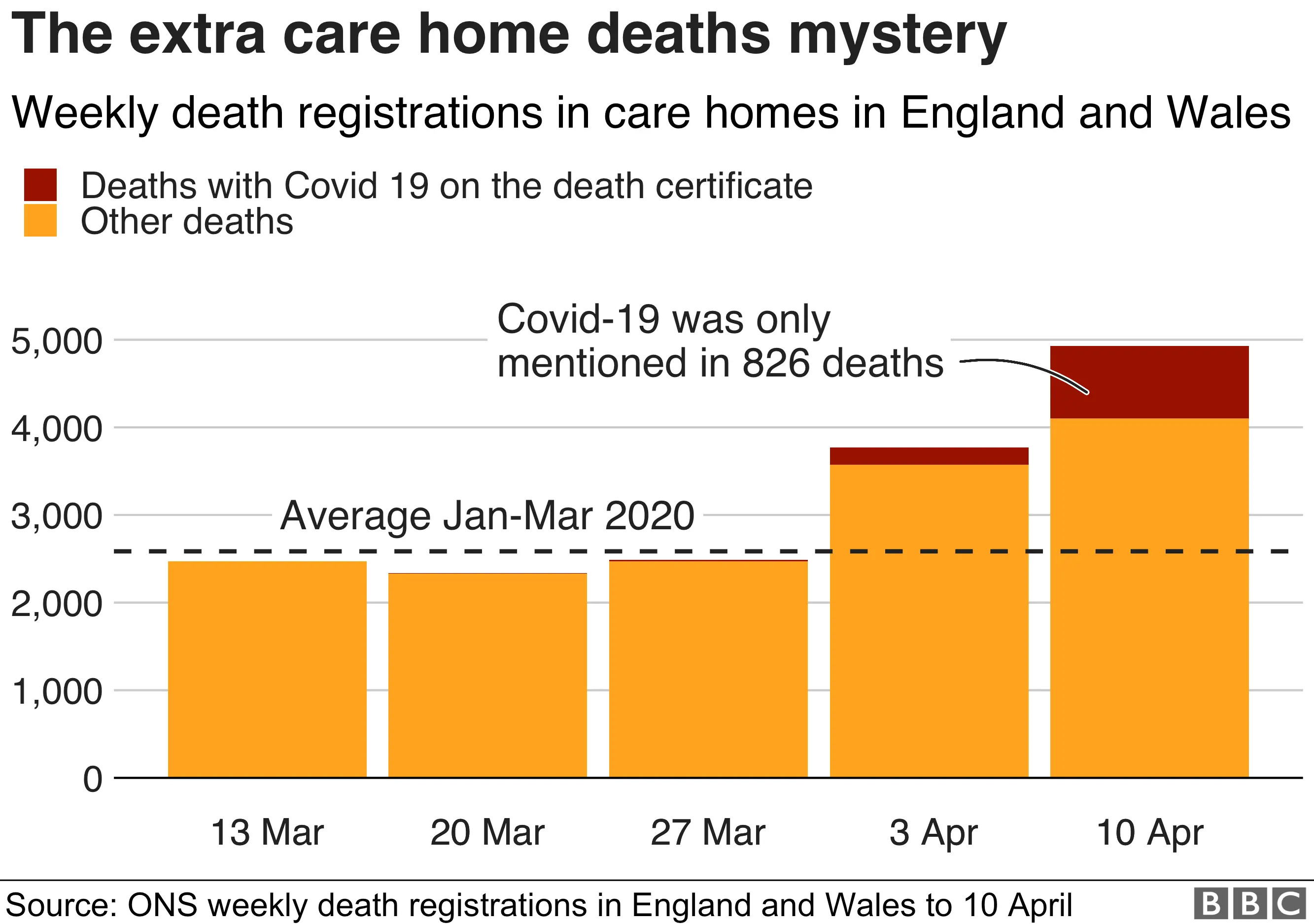

Care home deaths are rising

In comparison, the deaths in care homes are rising across the UK - and probably at a more rapid rate than the official figures show.

The ONS has been tracking this through death certificates, and because of this the data lags behind the hospital figures.

The latest information shows that up to 10 April, there have been just over 1,000 deaths so far in England and Wales. But that looks like it is a underestimate.

That's because during that week, and indeed the week before, there were actually many more extra deaths above what you would normally expect.

These extra cases did not mention coronavirus on the death certificate but experts believe they point to an under-reporting of coronavirus deaths.

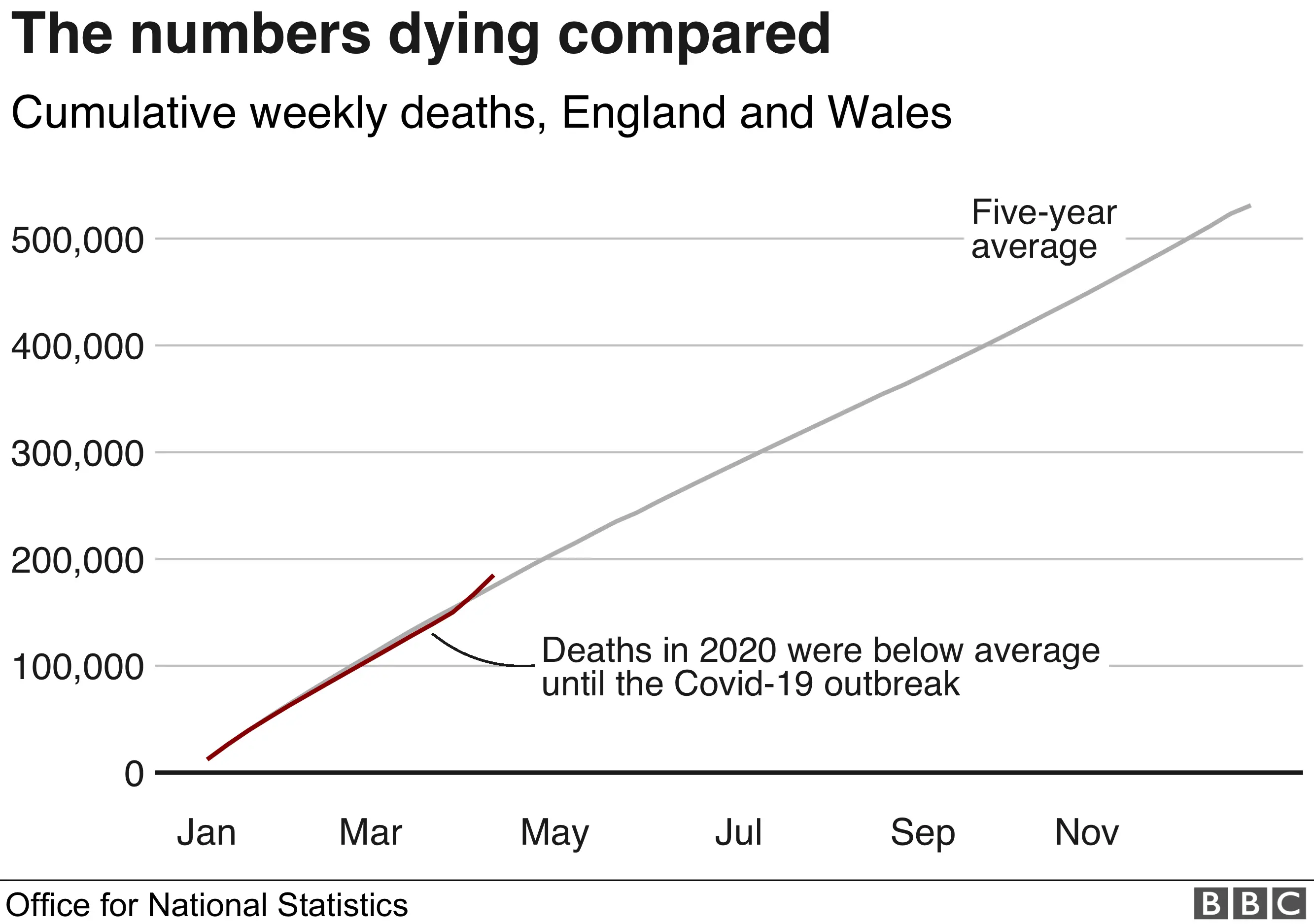

Are more people dying than expected?

It is noticeable that government officials have started talking about "all-cause mortality" when asked about the growing number of deaths.

They mean that the best way to judge the rising death rate is to track whether the total number of people dying is above average levels to get an idea of the number of excess deaths being caused.

Between 1,000 and 2,000 people die every day normally. If you look at the current weekly figures, which again lag behind by a week or so, the number of deaths has started increasing more rapidly than is normal.

The week leading up to 10 April saw the highest number of deaths in England and Wales in a single week - 18,500 - for 20 years. A similar pattern has happened in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

That was enough to push the total number of deaths in 2020 above what you would normally expect at this time of year - a situation which is bound to get worse as the deaths in the past week or so are counted in the ONS data.

How bad will it get?

What is not clear is what will happen over the course of the coming months.

It is possible, especially if the outbreak is brought under control, that the numbers dying could drop below average levels later in the year, thus reducing the level of excess deaths over time.

That is because there will be significant overlap between those at risk of dying with coronavirus and those at risk of dying anyway during the course of the year.

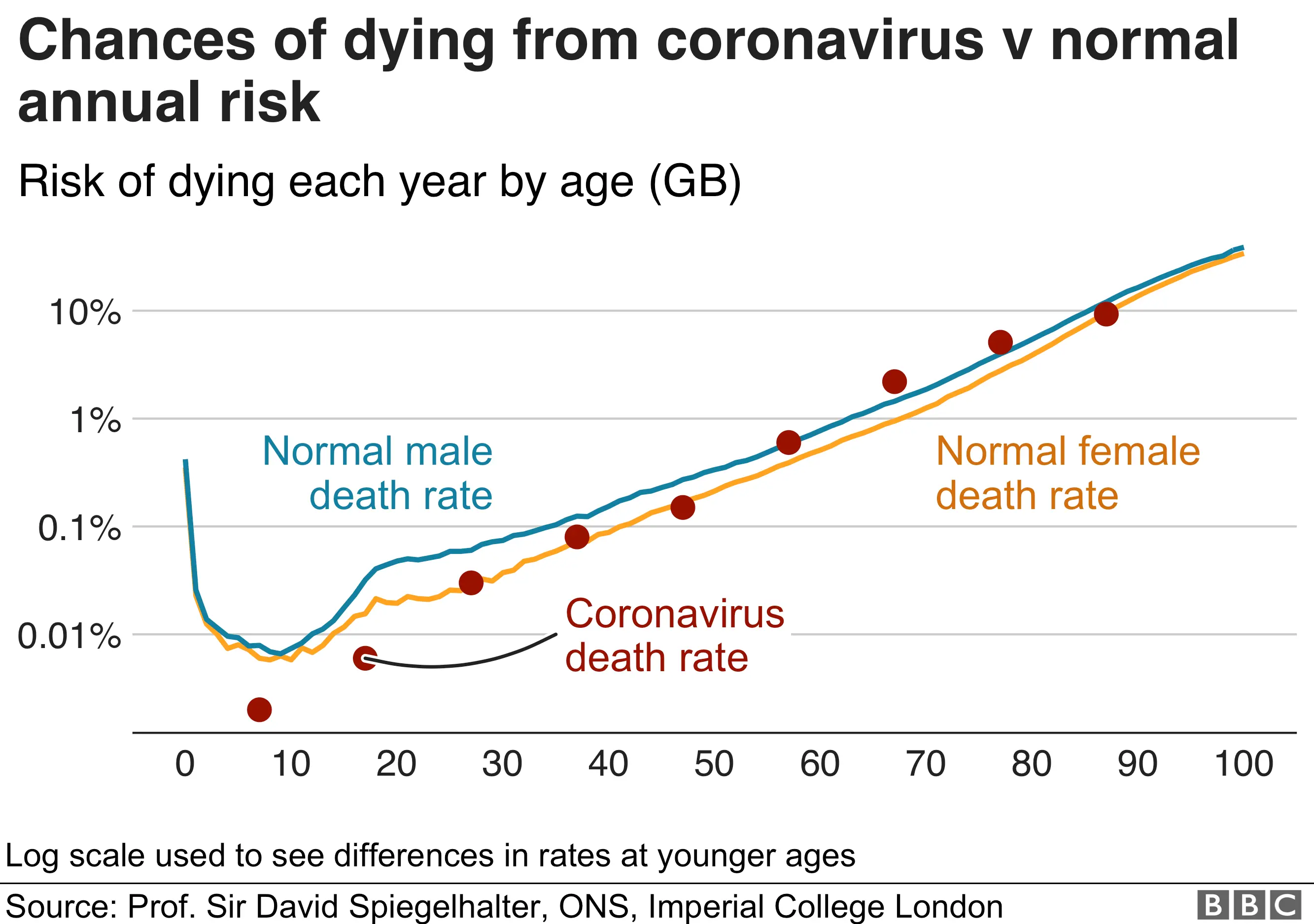

The risks are strikingly similar from the early 20s upwards - children are more at risk of dying from something else than if they are infected with the virus.

This does not mean the risk of death is doubled if you are infected, nor does it mean there is no extra risk.

It is also worth pointing out this is all based on those who are infected and show symptoms. There is evidence that significant numbers of people do not show symptoms, and therefore the overall risk of death from coronavirus may be even lower.

Going forward, what is crucial to help minimise extra deaths is to avoid a second peak after the lockdown is eased, and controlling outbreaks in care homes - unless a treatment or vaccine emerge.

But even that will not be enough. It is noticeable UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Witty has talked often recently about "indirect deaths".

These are deaths not from coronavirus but related to the lockdown: people who cannot access care for other conditions, such as cancer, strokes or heart attacks, and those who take their own lives or suffer ill-health because of emotional struggles and the economic downturn.

Steps will be needed to safeguard against these, and, therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that Sir Patrick says it is difficult to speculate how many will eventually die.

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

- EASY STEPS: What can I do?

- CONTAINMENT: What it means to self-isolate

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Should deaths be lower?

There are two main factors determining the number of deaths at this stage of the coronavirus pandemic - the health service's ability to cope and the point at which lockdown started.

In terms of the NHS, the UK has coped well, relatively speaking. Health Secretary Matt Hancock has said anyone who has needed intensive care has got it.

Currently more than a quarter of intensive care beds are available, while there are about 15,000 free beds on wards.

The distressing scenes in Italy where hospitals became overwhelmed have not materialised here.

But on the lockdown, there are questions to be asked.

The lack of early testing may have masked how widespread the virus was in the UK, says University of Oxford's Prof James Naismith, which resulted in delays announcing the lockdown.

Even a few days can have a "huge impact" on future cases and deaths, he says.