UK Biobank: DNA to unlock coronavirus secrets

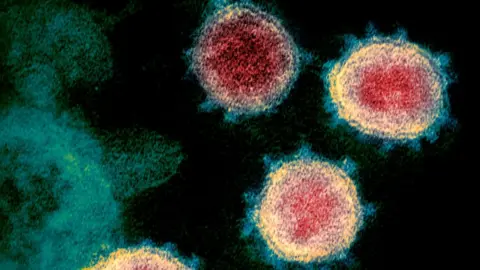

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryA vast store of DNA is being used to study why the severity of symptoms for coronavirus varies so much.

UK Biobank - which contains samples from 500,000 volunteers, as well as detailed information about their health - is now adding Covid-19 data.

It is hoped genetic differences could explain why some people with no underlying health conditions can develop severe illness.

More than 15,000 scientists from around the world have access to UK Biobank.

Prof Rory Collins, principal investigator of the project, said it would be “a goldmine for researchers”.

“We could go very quickly into getting some very, very important discoveries,” he said.

How do Covid-19 symptoms differ?

Some people with coronavirus have no symptoms - and scientists are trying to establish what proportion this is.

Others have a mild to moderate disease.

But about one in five people has a much more severe illness and an estimated 0.5-1% die.

How can UK Biobank help?

UK Biobank has blood, urine and saliva samples from 500,000 volunteers whose health has been tracked over the past decade

And it has already helped to answer questions about how diseases such as cancer, stroke and dementia develop.

Now, information about positive coronavirus tests, as well as hospital and GP data, will be added.

Prof Collins said: “We’re looking at the data in UK Biobank to understand the differences between those individuals.

“What are the differences in their genetics? Are there differences in the genes related to their immune response? Are there differences in their underlying health?

“So it is a uniquely rich set of data - and I think we will transform our understanding of the disease.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor what will scientists be looking?

Researchers will be scouring the entire genome, searching for tiny variations in DNA.

One area of particular interest is the ACE2 gene, which helps make a receptor that allows the virus to enter and infect cells in airways.

What about healthy people who become very ill?

In addition to the UK Biobank study, a team led by Prof Jean-Laurent Casanova, from the Rockefeller University, in New York, is planning to study people under 50 with no underlying medical conditions who are taken into intensive care units.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- WHAT WE DON'T KNOW How to understand the death toll

- TESTING: Can I get tested for coronavirus?

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

He told BBC News: “We are recruiting these patients worldwide, almost in every country.

“We have sequencing hubs distributed all over the world.

"They collect samples, they sequence the genomes of these patients,and then together we analyse them.”

Past research has shown some diseases, including flu and herpes, can make people with genetic variations - or inborn errors of immunity, as Prof Casanova calls them - especially ill.

“There are surprising inborn errors of immunity that render human beings specifically vulnerable to one microbe," he said.

“And this inborn error of immunity can be silent, latent, for decades, until infection by that particular microbe.

“What our programme does is to essentially test whether this idea also applies to Covid.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWho else is looking at coronavirus genetics?

Prof Andrea Ganna, from the University of Helsinki, in Finland, is leading a major effort to pull together genetic information on coronavirus patients from around the world.

“There are long-standing studies, involving hundreds of thousands of people, and other smaller ones collecting data on patients who test positive," he said.

"It’s such a huge diversity and there are a lot of countries involved and we will try to centralise it.”

In Iceland, for example, Decode Genetics has sequenced the genomes of about half the population.

It is now carrying out mass testing for coronavirus.

And every time someone tests positive, it then sequences the DNA genetic code of the virus to see how it changes as it spreads.

Chief executive Dr Kari Stefansson said: “There is the possibility that the diversity in people’s response to the virus is rooted in the sequence diversity of the virus itself - that we may have many strains of the virus in our community and some of them are more aggressive than others.

“The other possibility is that this may be rooted in genetic diversity in a patient. Or it may be a combination of both.”

Follow Rebecca on Twitter.