Coronavirus doctor's diary: 'The most urgent research race in living memory'

BBC

BBC

Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary says "we are running for our lives" as doctors search for a treatment for Covid-19, in a nationwide medical trial.

9 April 2020

There have been one-and-a-half million cases of Covid-19 around the world, and 55,000 in the UK, with over 6,000 people dying. It's hard to think of the peace when you're in the middle of the war. However, we do need an exit strategy.

A vaccine will be found, but this is at least a year away, and if we're going to save precious lives, we desperately need effective treatments today. To do that, we need to harness the best medical research in the UK.

Now is the time to combine all our bright research lights and shine them on to Covid-19.

That's why we at Bradford Royal Infirmary are taking part in the Recovery trial. It stands for Randomised Evaluation of Covid-19 Therapy, and is recruiting anyone over the age of 18 who is admitted into hospital with coronavirus.

All patients will be randomly allocated to one of five arms, and be given either a placebo or one of four experimental treatments. More than 130 hospitals are involved, including St Thomas' in London, where Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been being treated. As of today, towards the end of the second week, 2,000 patients have been recruited, of whom 30 are in Bradford.

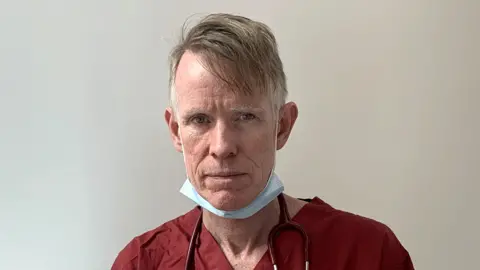

John Wright

John WrightProf John Wright, a medical doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research. He has looked after patients in epidemics all over the world, including cholera, HIV and ebola outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa. Over the next few weeks he will be reporting for the BBC on how his hospital, the Bradford Royal Infirmary, is coping with Covid-19.

Read his previous diary entries:

This is one of the advantages of having a National Health Service. We've never been so co-ordinated, having one big trial, and trying to recruit everybody in the country.

It's the biggest and most urgent research race in living memory, and we are running for our lives.

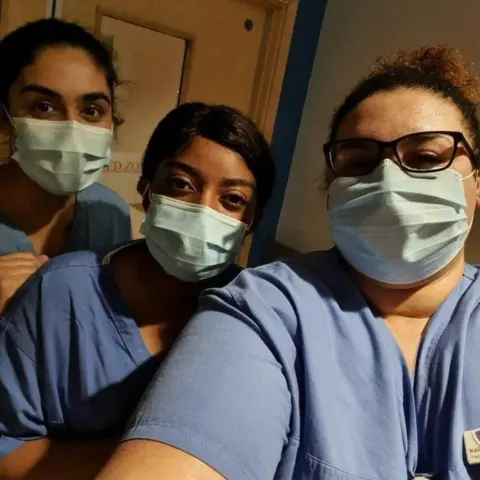

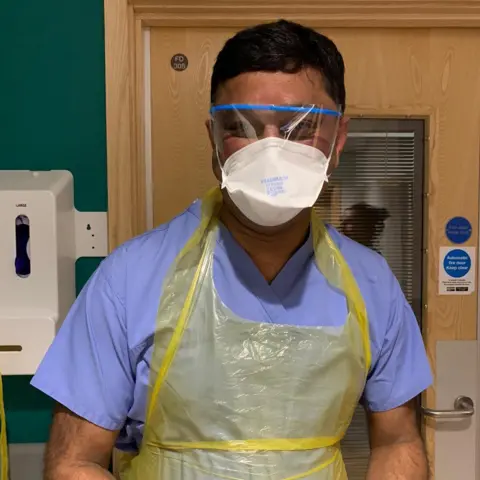

On Tuesday I accompanied Dr Dinesh Saralaya on the morning ward round in Ward 31, which is where the first of our Covid-19 patients were admitted, and which remains the centre of our fightback. Since then our infectious "red zone" has expanded - the red tide constantly gets higher and higher, seeping through the hospital. We've had more than 200 cases and 30 deaths.

Dinesh introduced me to a patient in his 40s who described the symptoms he'd started having about 12 days earlier.

"The first three days I'd say it was shivers, and temperature and then I lost the appetite and my taste. And then my cough got really bad. And at night time it was just like an attack of cough - and then it just doesn't stop," he said.

He'd also been having nose bleeds.

After three days in hospital he was already feeling a lot better.

Listen to John Wright

- John Wright is recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio 4's The NHS Front Line

- You can hear the next episode at 11:00 on Tuesday 14 April, catch up with the previous episodes online, or download the podcast

At that point it was time to turn him on to his stomach - "tummy time", as the nurses call it - which often makes it easier for patients to breathe.

It was explained to him when he consented to take part in the trial that he might be given a placebo. The other four possibilities are:

- Hydroxychloroquine, the antimalarial drug that President Trump said he had a good feeling about - which then led to a spate of overdoses and acute shortages

- Kaletra, a combination of antiretroviral drugs used in treating HIV

- Dexamethasone, a steroid, which is an old favourite in medicine when we don't quite know what's going on

- Interferon, a cytokine, which may help fight the infection

The danger zone is between the 10th and 15th days, so this patient is not yet in the clear, even though he says he is feeling better.

Dinesh explained to him that the treatment would stop the day he leaves hospital and that the main beneficiaries would be future patients, because the data from the trial would show which treatment was most effective.

Afterwards I asked Zulfi Karim, president of the Bradford Council of Mosques, how he thought the city's Muslim community - who make up just under a third of the population - were feeling about the pandemic and the measures taken to tackle it.

"I think it has now finally dawned on everybody how deadly this is," he said.

"Reality has hit home. I think the community leaders absolutely feel that the lockdown of mosques and suspension of gatherings was the right thing to do. And now it's very much about 'How do we ride this out?'"

The decision to close mosques in the city was taken on 20 March, days before the government-imposed lockdown came into effect. But unfortunately, for Zulfi it was already too late. He started displaying symptoms of Covid-19 and has been really ill since. He is finally showing signs of recovery, after a period in which I was very worried about him.

I put it to Zulfi that coronavirus has highlighted inequalities. If you live in a nice house with a nice garden, lockdown isn't too bad, but if you're living in an overcrowded house in the inner city, it's really tough.

He agreed.

"It's tough and it's not just tough, but I think what we're going to find once we get out the other side, is that those areas are probably where we've had the highest number of fatalities as well."

Follow @docjohnwright on Twitter

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health