Coronavirus: Testing, PPE and ventilators - how has the government done?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK government is facing mounting criticism for its approach to combatting coronavirus.

From testing to protective equipment for staff and NHS preparedness, questions are being asked.

But how fair is this? And has the government been keeping its promises?

Was the lockdown delay a mistake?

The first positive coronavirus case was identified at the end of January.

In the first month or so the focus was on containment - all the public were asked to do essentially was wash their hands regularly, while officials traced the contacts of infection individuals.

Then on 10 March the government announced the first steps it wanted the public to take as it moved away from containment, asking them to self-isolate for seven days if they had symptoms.

But even then it was not to be immediate - officials said they would only need to start to do it in 10 to 14 days' time.

However, this approach soon unravelled - with modelling suggesting the UK was heading for a major epidemic that could cost 250,000 lives.

Bit by bit the measures were ramped up until a lockdown was announced on 23 March - by that stage more than 300 people had died.

Some have argued the delays lost the UK valuable time and left the government playing catch-up.

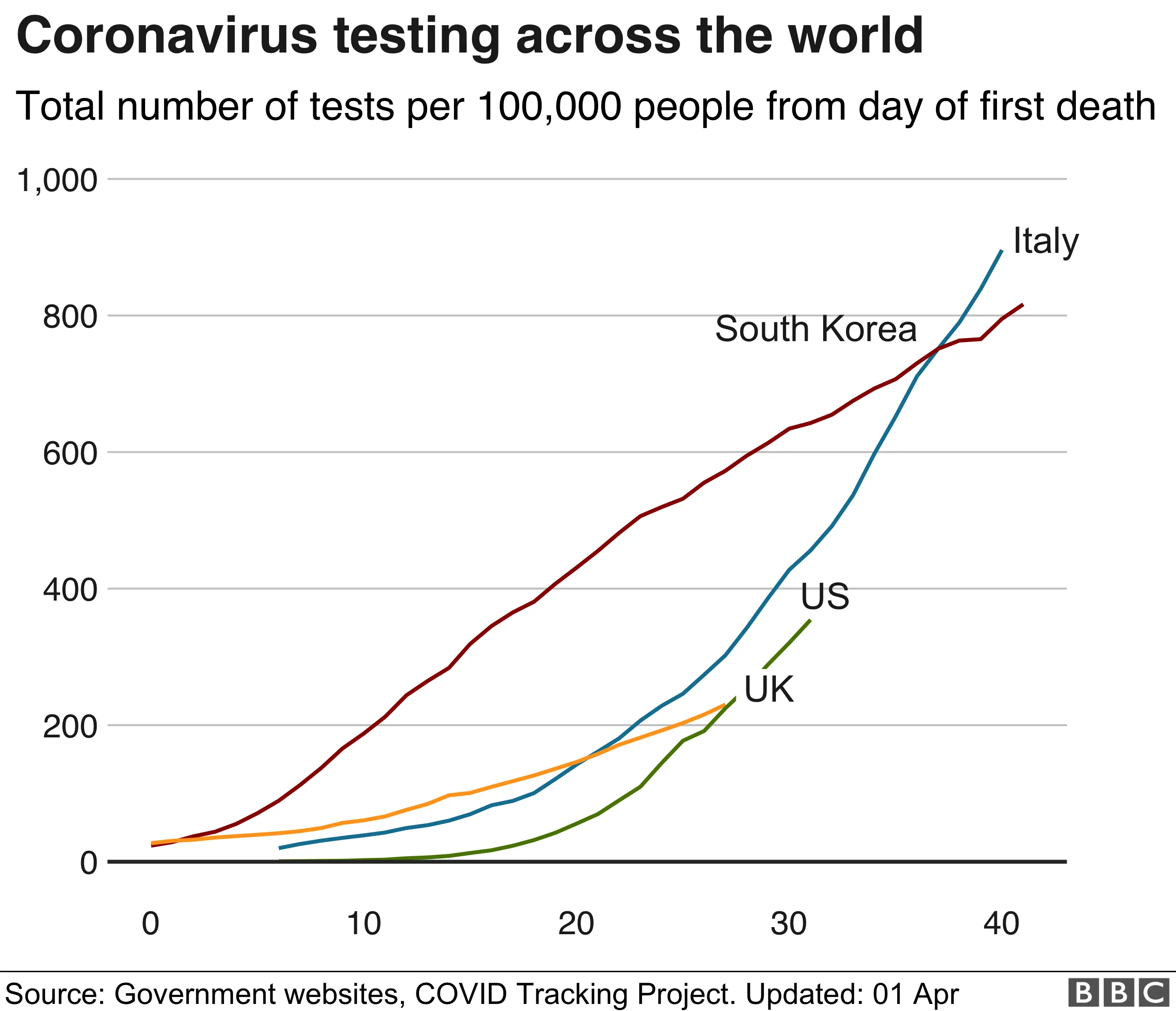

Why is the UK playing catch-up on testing?

Germany - which now tests three times as many people as the UK each day per head of population - developed a diagnostic test (to see if someone currently has the virus) a month before the UK did.

But it had some major advantages - more labs and a bigger manufacturing industry for starters. It has been less susceptible to the shortages of testing kits and chemicals which have affected the ability of not just the UK, but also countries such as Italy and France.

However, legitimate questions are still being asked about why the UK was slow to expand testing capacity beyond the eight Public Health England labs it was using initially.

Only in recent weeks have officials started using hospital labs and - from this week - universities, research institutes and private sector facilities are coming on board.

Prof Paul Cosford, of Public Health England, seemed to acknowledge mistakes had been made when he told the BBC on Thursday "everybody involved is unhappy" with the situation.

It meant the goal to reach 10,000 tests a day by Monday was not achieved until Wednesday. Although the government is confident capacity can be ramped up quickly now, promising 100,000 a day by the end of the month.

Meanwhile, the UK has tried to get ahead of the curve on antibody testing - which checks if someone has had the virus and therefore developed some immunity - by ordering 3.5 million doses in advance.

These will be vital for a variety of reasons, but many of them are more long-term.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: How to self-isolate and exercise

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health

The great benefit will be discovering whether there has been widespread transmission of the virus in the community.

The big unknown is how many cases there have been that have not shown symptoms.

If this has happened significantly - some have suggested half of those infected may not show symptoms - it could signal herd immunity has been achieved by default and allow life to return to normal, certainly for those who have been exposed.

But there is no guarantee these antibody tests will work. University of Oxford is looking at them now.

How much protective equipment is there?

The scramble to obtain protective equipment for staff - with unions warning doctors and nurses' lives are being put at risk - has led to lots of criticism, with suggestions some doctors would down tools if they are not made available.

The government has offered frequent bulletins on the volume of equipment being delivered.

On 19 March Health Secretary Matt Hancock said that in the previous 24 hours, 2.6 million masks and 10,000 bottles of hand sanitiser had been delivered. And there was plenty more. "We've got all this in storage in case there's a pandemic like this and there are literally lorries on the road right now."

This week Business Secretary Alok Sharma said 390 million items of protective equipment had been delivered in the past fortnight,

And yet that contrasts with repeated reports of shortages in some parts of the NHS. British Medical Association leader Dr Chaand Nagpaul has described the situation as "unacceptable".

But again the UK is not alone in this. Other countries have been caught out too.

The army has been deployed to ensure the equipment gets out to not only hospitals, but also GPs and care homes.

But each day the BBC is hearing from front-line staff worried about their safety.

The problems are far from resolved.

What about ventilators?

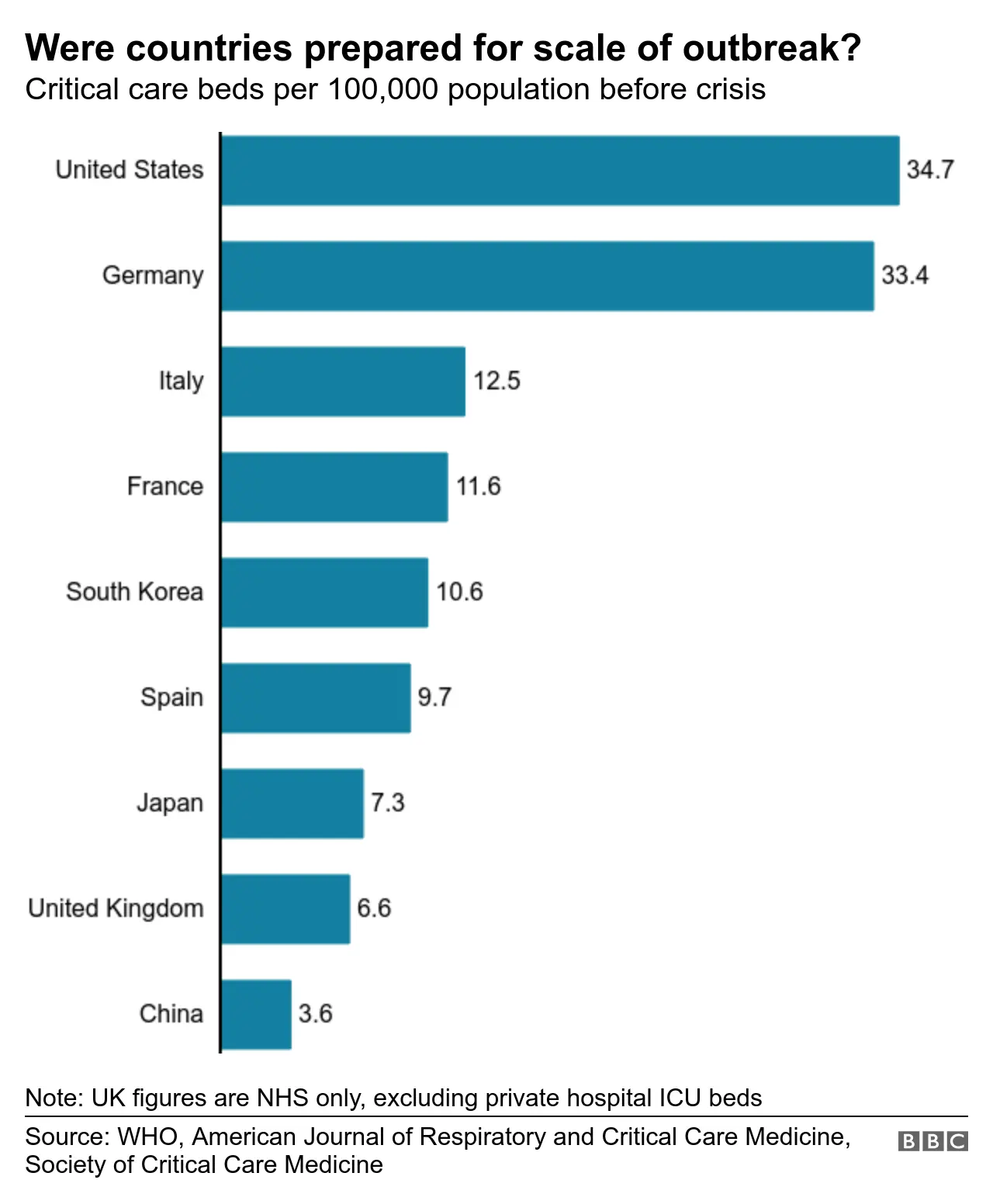

Chris Hopson, head of NHS Providers, which represents hospitals, says ventilators will be "crucial" in treating coronavirus patients, lamenting the lack of equipment available.

The UK had to start from a low base with fewer ventilators per head than many nations. However, the NHS figures do not include ventilators in the private sector, whereas other countries' totals usually do.

The NHS managed to double its ventilator numbers in a matter of weeks from 4,000 to 8,000 - with 1,200 coming from the private sector.

That has been impressive. But doubts remain about how quickly the target of 30,000 ventilators will be reached.

And there has been ambiguity in the the government's messaging. On 23 March, Mr Hancock was asked on the Today programme: "Have any new ones been made?"

He replied: "Yes, we've made serious progress on that. There's now over 12,000 that we have managed to get to."

But nearly two weeks later the NHS still only has access to 8,000 ventilators - although new deliveries are expected in the coming weeks.

Transforming hospitals

But as much as there has been criticism of the government's strategy and the speed at which it ramped up testing, there have been voices who have cautioned against being too critical.

Prof Mark Woolhouse, an expert in infectious diseases at Edinburgh University, has said as this virus was new, there would "inevitably be many gaps and uncertainties" in understanding.

And credit should certainly be given for some of the work that has gone on behind the scenes to transform hospitals - although arguably it is NHS staff's determination and ingenuity that has helped this happen.

Operating theatres and recovery rooms have been transformed into temporary intensive care facilities for coronavirus patients.

Thousands of beds on general wards have also been freed up. With NHS Nightingale on the brink of opening and plans for big field hospitals in other cities there is plenty of scope to grow capacity.

It is an advantage the Spanish and Italian health systems could not achieve.

Will it be enough? With the number of cases going up, we are on the brink of finding out.

Additional reporting by Oliver Barnes and Nicholas Barrett