Coronavirus doctor's diary: Why are people stealing hospital supplies?

Victor de Jesus

Victor de Jesus

March 29 2020

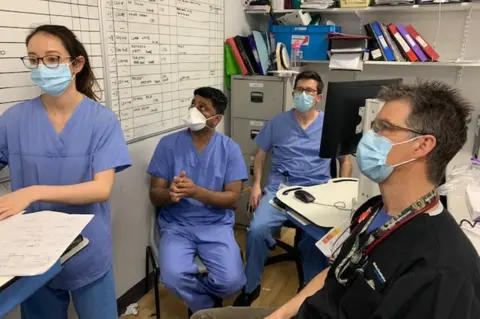

The Covid-19 outbreak has already brought a range of challenges for front line medical staff - shortages of equipment, doctors and nurses falling ill, and even thieves trying to break in and steal valuable supplies. In the first of a series of diaries, Dr John Wright reports on preparations at Bradford Royal Infirmary.

Following the UK-wide lockdown, the hospital followed suit in a bid to limit transmission of the coronavirus.

Eighteen entrances across the 26-acre site were sealed off and everyone is now funnelled through one main door. Staff must show their passes and patients are no longer allowed to bring visitors with them, even when they're coming in for cancer treatments.

But not long before millions of people across the UK stepped out of their houses and applauded NHS workers, one man carefully dressed in doctor's scrubs. He even completed his disguise with a stethoscope. He then attempted to bluff his way past a security guard, who demanded to see his pass, and when he was caught he made a run for it.

John Wright

John WrightThere had already been thefts of surgical gowns, masks, protective equipment and sanitisers. It's possible this man was after supplies like these, or possibly drugs. The head of the Bradford Hospital Trust, Mel Pickup, has heard that there are now shortages on the streets because of the epidemic. "People who have addictions need to feed them," she says. "Where do you go if you want drugs and you can't get those on the street any more?"

Hospital scrubs are now having to be stored under lock and key.

Front line diary

John Wright

John WrightProf John Wright, a medical doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research. He has looked after patients in epidemics all over the world, including cholera, HIV and ebola outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa. Over the next few weeks he will be reporting for the BBC on how his hospital, the Bradford Royal Infirmary, copes with Covid-19.

We know from what's been happening in Italy how Covid-19 is likely to affect us in Bradford. Multi-generational households are common in Italy and also here - particularly among Pakistanis, who make up just under a third of the population and are genetically predisposed to heart disease and diabetes, the very underlying health conditions that can make Covid-19 particularly deadly. There are poor areas in Bradford, and some white people have high levels of lung disease from smoking.

We know there is a tsunami coming.

John Wright

John WrightAt present there are 16 intensive care beds in the hospital and that's usually enough, but it's been projected that we could be treating 500 people at the peak of the epidemic, so we need to ramp up very quickly. A disused ward has been fitted with ventilators and other wards are being reconfigured.

Dr Debbie Horner, in charge of Covid-19 intensive care planning, says accepting the scale of what's happening has been like going through the stages of bereavement. "Initially you've got a kind of shock and then comes denial and acceptance," she told me. "As an intensive care community, most of us are now in the kind of acceptance phase."

Find out more

- John Wright is recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio 4's NHS on the Front Line

- You can hear the next episode at 11:00 on Tuesday 31 March, catch up with the first episode online, or download the podcast

We have also been taking steps to obtain more personal protective equipment.

Our stocks of surgical masks are good, but supplies of more effective PPE masks and eye-protection visors were running low. So a consultant, Dr Tom Lawton, went to Screwfix to buy industrial masks - and then found a way of attaching medical filters to them, using a 3D printer he keeps in his garage. Another went to a builders' merchants and bought 2,000 pairs of goggles.

John Wright

John WrightConsultant anaesthetist Dr Michael McCooe, meanwhile, started looking into ways of sterilising masks, so they could be re-used, and called Whittaker's gin distillery in the Yorkshire Dales. Mr Whittaker himself answered the phone, and said that his 96% proof gin could be diluted for the purpose.

"He was very happy to donate to us," Dr McCooe told me. "He'd been looking into whether they could supply more alcohol to the health service and whether they could make hand sanitiser. It's a great step forward and now we just need somewhere safe to store it all!"

But in the last week or so, both Debbie Horner and Michael McCooe have gone into isolation.

John Wright

John WrightDebbie called me on the afternoon of Friday 20 March, just before we were going to run our Covid-19 case rehearsals, to say that she had some mild symptoms and was going to go home, just to be on the safe side. We haven't yet started testing staff for the virus, but given how important she was, we felt that we needed to make an exception - and so we arranged for a surreptitious visit to Accident and Emergency on Saturday morning to swab for Covid-19 and other more likely seasonal viruses.

Then, on Monday, our microbiologist rang to drop the bombshell: the swab had come back positive.

A day later the clinical director of urgent care, Dr Sam Khan, started to feel unwell. And then Dr Michael McCooe was forced to self-isolate because his partner, another anaesthetist at the hospital, was ill. It seems likely that we were infecting one another as we planned our response to coronavirus, until we got our social distancing house in order.

If we lose many more of our senior clinical leaders at this early stage of the campaign it would be a disaster.

We have a rapidly increasing number of cases, but it still feels like the calm before the storm. And the eye of the storm will be in our Intensive Care Unit.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- STRESS: How to protect your mental health

- LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak