Why aren't we living longer?

Yuri_Arcurs/Getty

Yuri_Arcurs/GettyFor the best part of two centuries people's life expectancy has been improving at a pretty rapid and consistent rate.

In the 1840s people did not live much past 40 on average. But then improvements in nutrition, hygiene, housing and sanitation during the Victorian period meant by the early 1900s life expectancy was approaching 60.

As the 20th Century progressed, with the exception of the war years, further gains were made with the introduction of universal health care and childhood immunisations.

From the 1970s onwards, medical advances in the care of stroke and heart attack patients in particular, saw big strides continue to be made

So much so that by the start of the 21st Century, life expectancy at birth had reached 80 for women and 75 for men.

And so it continued, with an extra year of life being added every four years or so.

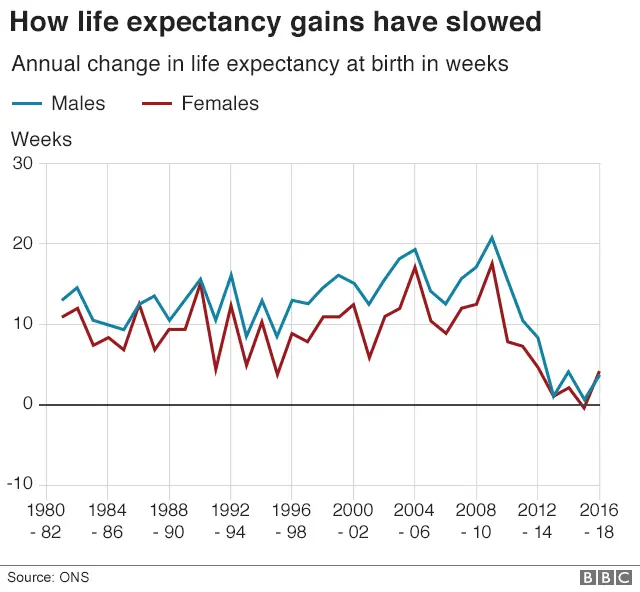

But then it suddenly stopped - or rather rapidly slowed. The turning point was 2011.

A blip or long-term trend?

Initially many experts wondered if it might be a blip. Certainly 2015 was an exceptional year when the number of deaths spiked - the winter was particularly bad, and this was linked to the strain of flu circulating.

But it is now clear there is more to it than just a short aberration

The latest figures released by the Office for National Statistics for 2016-2018 - these things are measured on a rolling three-year basis - are the first for a few years to exclude that bad winter.

And while there has been a little improvement, it is still way down on what has been seen previously.

On current trends, it will take more than 12 years for people living in the UK to gain an extra year of life.

So what are the causes?

One suggestion put forward is that after so many years of gains, humans are just reaching the upper limits of their lifespan.

The oldest living person for whom official records exist was French woman Jeanne Calment, who was 122 when she died - but that was more than 20 years ago.

Alamy

AlamyResearch published by the journal Nature has claimed the limit - bar those extreme few like Ms Calment - is around 115.

But there are plenty who dispute this. In fact a US geneticist, David Sinclair, has written a book called Lifespan which argues that by boosting genes associated with longevity, people may be able to live much longer.

Whatever the truth, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the UK's population should not have reached its limit on lifespan.

Japan, for example, which already has longer life expectancy, has seen bigger increases in recent years than the UK.

In fact, out of the wealthier nations the ONS looked at, there was only one country which had a significantly worse record than the UK - the US - although plenty have seen improvements slow down.

Complex range of factors

ONS ageing expert Edward Morgan said there was likely to be a "complex" range of factors behind the trend - and he would like more work done to investigate it.

Public Health England has already done some. Its report, published last year, puts forward a number of factors.

One possible explanation is that there has not been a big medical or health game-changer in the past couple of decades.

As people stop dying from one thing, another disease takes its place.

With greater numbers surviving heart attacks and strokes and cancer, the death rate from dementia has started to rise.

And with the medical community struggling to find ways to slow the disease - never mind cure it - life expectancy has been curbed.

The PHE report also looked at the impact of austerity - something former World Health Organization adviser Prof Michael Marmot has already suggested is playing a role.

The evidence shows that poorer people have seen the biggest decline in improvements - and the fact they would be more affected by a squeeze on care, health and welfare spending "could indicate" government spending has played a role, PHE said.

But the report was far from being conclusive.

What is sure, however, is that the longer this trend goes on, the more pressing it will become to find an answer.