Early brain 'signs of Parkinson's' found

Getty Images

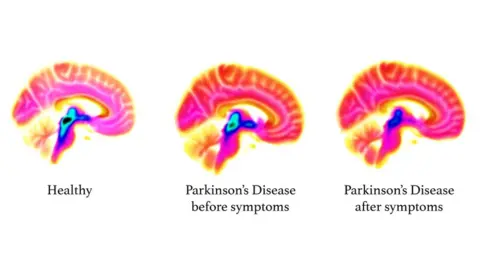

Getty ImagesScientists say they have identified the earliest signs of Parkinson's disease in the brain, 15 to 20 years before symptoms appear.

Scans of a small number of high-risk patients found malfunctions in the brain's serotonin system, which controls mood, sleep and movement.

The King's College London researchers say the discovery could lead to new screening tools and treatments.

Experts said larger studies and more affordable scans were needed first.

Parkinson's is a progressive neurological condition affecting about 145,000 people in the UK.

The main symptoms are shaking, tremors and stiffness but depression, memory and sleep problems are also common.

Traditionally, the disease is thought to be linked to a chemical called dopamine, which is lacking in the brains of people with the condition.

Although there is no cure, treatments do exist to control symptoms - and they focus on restoring dopamine levels.

But the KCL research team, writing in Lancet Neurology, suggest that changes in the brain's serotonin levels come first - and could act as an early warning sign.

King's College London

King's College LondonThe researchers looked at the brains of 14 people from remote villages in southern Greece and Italy who all have rare mutations in the SNCA gene, making them almost certain to develop the disease.

Half of this group had already been diagnosed with Parkinson's and half had not yet shown any symptoms, making them ideal for studying how the disease develops.

By comparing their brains with another 65 patients with Parkinson's and 25 healthy volunteers, the researchers were able to pinpoint early brain changes in patients in their 20s and 30s.

These were found in the serotonin system, a chemical which has many functions in the brain, including mood, appetite, cognition, wellbeing and movement.

'Could open doors'

Lead study author Prof Marios Politis, from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King's, said the abnormalities had been found long before movement problems had begun and before dopamine levels had changed.

"Our results suggest that early detection of changes in the serotonin system could open doors to the development of new therapies to slow, and ultimately prevent, progression of Parkinson's disease," he said.

Prof Derek Hill, professor of medical imaging at University College London, said the research provided some valuable insights but also had some limitations.

"Their results may not scale up to larger studies," he said.

"Secondly, the imaging method they used is highly specialised and limited to a very small number of research centres, so isn't yet usable either to help diagnose patients or even to evaluate novel treatments in large clinical studies.

"The research does, however, provide encouragement for the approach of trying to treat Parkinson's disease at the earliest possible stage, which is likely to be the best chance of preventing the rising number of people whose lives are destroyed by this hideous disease."

Dr Beckie Port, research manager at charity Parkinson's UK, said: "Further research is needed to fully understand the importance of this discovery - but if it is able to unlock a tool to measure and monitor how Parkinson's develops, it could change countless lives."