Why are some places gay-friendly and not others?

EPA

EPAWhen Taiwan became the first place in Asia to legalise same-sex unions, hundreds of gay people marked the occasion by registering to marry.

It marked a significant change on the island, where the majority of people only relatively recently became supportive of same-sex relationships.

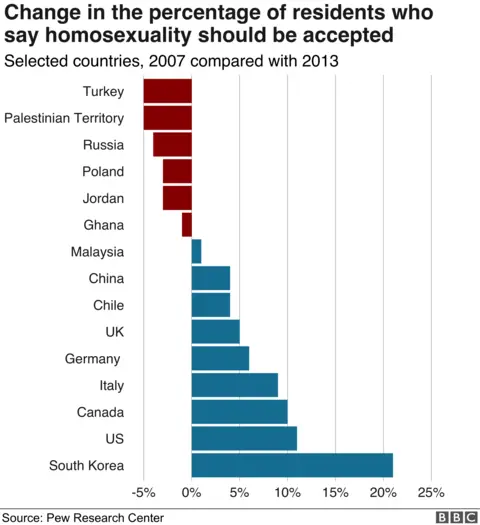

In many other places there has also been a shift - often a rapid one - towards more liberal attitudes.

For example, in 2007, one in five South Koreans said homosexuality should be accepted, - but, by 2013, that figure had doubled.

Attitudes among the public also appear to have softened in other places including Argentina, Chile, the US, Australia, India and many in Western Europe.

But these changes do not always mean full equality. In Taiwan, for example, the government stopped short of granting full adoption rights.

Elsewhere, some nations are bringing in stricter anti-gay laws and same-sex relationships remain illegal in about 69 countries. On Friday, Kenya's High Court upheld a law banning gay sex.

Pockets of opposition

In some countries, opposition towards gay relationships is deeply entrenched and may be growing.

For example, in Ghana, where gay sex can be punished with a prison sentence, attitudes have become even less accepting.

In 2013, a poll suggested 96% of Ghanaians believe society should not accept homosexuality.

Elsewhere, official punishments for gay sex may provide insights into how residents, or at least their leaders, view homosexuality.

For example, Brunei recently made sex between men punishable with death through stoning, although it has since backtracked on this.

Another issue is that while laws and perceived attitudes may appear to have become more relaxed in some countries, the reality may be very different for the LGBT community there. For example, while Brazil's Supreme Court has recently voted in favour of making homophobia and transphobia crimes illegal, it did so in response to a large number of killings of LGBT people.

So, why does support for gay and lesbian people vary so much around the world?

Studies suggest the reasons are often linked to three factors - economic development, democracy and religion.

One theory is that a nation's economy shapes the attitudes of its people - including how they feel about LGBT rights.

Often, poorer nations tend to be less supportive, partly because cultural values tend to focus more on basic survival.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen people are concerned about things like clean water, food, shelter and safety, they can become more reliant on others.

This dependency tends to promote strong group loyalty - increasing support for its norms, including "traditional" heterosexual family structures.

People living in richer nations, by contrast, tend to have a lot more security.

As a result, they are more likely to have freedom to make the decisions that suit them, and to believe in self-expression.

Not everyone in richer countries is more tolerant of gay relationships, but the data we have indicates they tend to be more supportive.

Democracy is also thought to play a role.

In democracies, principles like equality, fairness, and the right to protest are more likely to form part of the actions of government and residents.

As a result, people who are sometimes seen as different, like gay and lesbian individuals, may be more likely to gain acceptance.

But people can need time to adapt to democracy.

Compared with longer-term democracies, former communist nations such as Slovenia and Russia appear to have been slower to develop more tolerant attitudes.

Another factor is the role of religion.

Western Europe, with its relatively low levels of religious belief, has been at the forefront of legalising same-sex marriage. Denmark, Belgium, Norway, Spain and Sweden were among the first countries to do so.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome Middle Eastern and African nations, where Islam or conservative Protestant religious faiths are most commonly practised, have some of the least tolerant attitudes.

Gay sex is illegal in almost half of the countries in Africa and Asia, with between 60% and 98% of people there saying that religion is "always important". This is much higher than in Europe, where gay sex is legal in all countries.

But while richer, more democratic and less religious nations tend to be more tolerant, there are many exceptions.

China, for example, has low levels of religious beliefs, but polls suggest its people are a lot less supportive of gay rights than their Taiwanese neighbours.

Shift in attitudes

Nations have always differed in terms of economic development, democracy and religion. So, why have attitudes and policies changed so much over the last 20 years?

One suggestion is that attitudes change as older generations pass away and are replaced by younger, more liberal people.

Another is that people of all different age groups may change their views and some research does suggest this has been the case.

In the US and many other nations, popular culture and the media appear to have played a role in the rapid liberalisation of attitudes.

From the 1990s onwards, some highly likeable gay and lesbian television characters - such as Will from Will and Grace - and TV personalities like Ellen DeGeneres began to appear. Popular culture makes it possible for people who would not necessarily know an openly gay individual to know one in a virtual sense.

Real life contact is also important, as it's more difficult to dislike a gay or lesbian person who is a friend or family member.

In the US, 22% of people in 1993 said they had a close friend or family member who was gay or lesbian. By 2013, 65% said that they did.

In this way the "coming out" movement, which encourages people to self-disclose their sexual or gender identity, has been highly successful.

Nevertheless, it cannot be assumed that all countries will, sooner or later, introduce laws that are more gay-friendly.

Some view being gay as a Western import, and may feel that the US and Europe are using economic power to impose their will on them.

For example, in 2009 Uganda considered a bill which would have made gay sex punishable with death in some circumstances. In response, several nations threatened to cut their funding, and the World Bank postponed a $90m (£70.7m) loan.

Similarly, Turkey has struggled to walk a thin line between supporting conservative Islamic views and maintaining policies that the EU would support.

There is also an argument that Brunei's initial decision to introduce the death penalty for gay sex may be an attempt to appeal to Muslim tourists and investors.

Elsewhere, political candidates may back harsh laws as a way to generate publicity and gain public support.

Attitudes and policies in many nations have clearly been shifting.

But the suggestion that more will follow in their footsteps is not a foregone conclusion.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Amy Adamczyk is Professor of Sociology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the Programs of Doctoral Study in Sociology and Criminal Justice at The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie