Dementia: The greatest health challenge of our time

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDementia is the greatest health challenge of our time, the charity Alzheimer's Research UK has warned.

Dementia was first described by the German doctor Alois Alzheimer in 1906 after he performed an autopsy on a woman with profound memory loss.

What he found was a dramatically shrunken brain and abnormalities in and around nerve cells.

At the time dementia was rare and was then barely studied for decades.

But today somebody is diagnosed with it every three seconds, it is the biggest killer in some wealthier countries and is completely untreatable.

So what is this disease? Why is it becoming more common? And is there any hope?

Is dementia the same as Alzheimer's?

No - dementia is a symptom found in many diseases of the brain.

Memory loss is the most common feature of dementia, particularly the struggle to remember recent events.

Other symptoms can include changes to behaviour, mood and personality, becoming lost in familiar places or being unable to find the right word in a conversation.

It can reach the point where people don't know they need to eat or drink.

Alzheimer's disease is by far the most common of the diseases that cause dementia.

Others include vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, fronto-temporal dementia, Parkinson's disease dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the newly discovered Late.

Is it really the biggest health problem of our time?

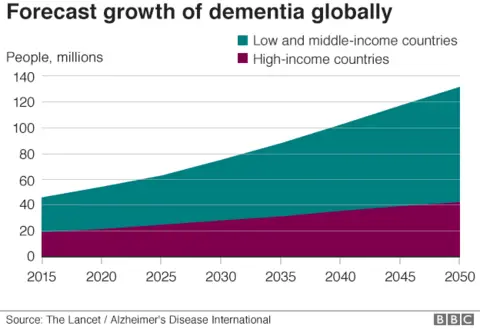

Globally around 50 million people are currently living with dementia.

But cases are predicted to soar to 130 million by 2050 as populations age.

According to the World Health Organization, deaths from dementia have doubled since 2000 and dementia is now the fifth biggest killer worldwide.

But dementia has already claimed number one spot in some richer countries.

In England and Wales, one in eight death certificates cite dementia.

There is also a key difference with other major killers such as cancer or heart disease, because there is not a single treatment that either cures or slows the pace of any dementia.

"Dementia certainly is the biggest health challenge of our time," Hilary Evans, chief executive of the charity Alzheimer's Research UK, told the BBC.

"It's the one that will continue to rise in terms of prevalence, unless we can do something to stop or cure this disease."

As the disease progresses, people eventually need full-time care and the annual cost of looking after people with dementia is in the region of $1 trillion a year.

Why is it becoming more common?

The answer is simple - we are living longer and the biggest risk factor for dementia is age.

That is why huge increases in dementia cases are predicted for Asia and Africa.

With a more philosophical hat on, you can see dementia as the price we pay for progress in treating deadly infections, heart attacks and cancer.

Although there is an unexpected and hopeful trend emerging that has surprised some in the field - the proportion of elderly people getting dementia is falling in some countries.

Studies have shown the dementia rate (the number of cases per 1,000 people) falling in the UK, Spain and the US and stabilising in other countries.

This is largely being put down to improvements in areas like heart health and education which in turn benefit the brain.

If I live long enough, will I get dementia?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNot necessarily.

There used to be a public perception that dementia was a normal part of the ageing process.

However, the research is clear - dementia is caused by disease.

And some people who live well into their 90s and beyond have brains that remain remarkably clear of any signs of dementia.

Prof Tara Spires-Jones, the deputy director of the centre for discovery brain sciences at the University of Edinburgh, said: "I think there are some people who would be fine, even if they lived for another 100 years."

Why do trials of drugs keep failing?

Be in no doubt - even a drug that just slows the progression of dementia would make someone a fortune.

It is not for the want of trying that there is no treatment for dementia.

Aducanumab, a drug that many hoped would work in Alzheimer's disease, is just the latest to fall by the wayside.

In March this year, Biogen and Eisai announced their drug was unlikely to be effective and ended the trial early.

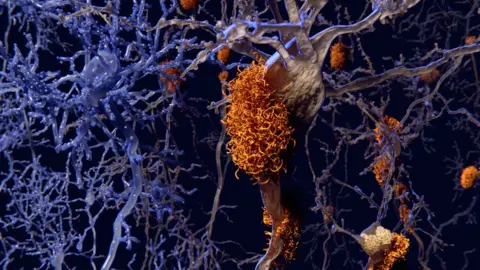

Aducanumab, like those that have failed before, had been designed to target a toxic protein called amyloid beta that builds up inside the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

If you go back to Dr Alzheimer in 1906, then some of the abnormalities he found in that brain autopsy were plaques of amyloid beta.

SPL

SPLSo a clear connection between amyloid beta and Alzheimer's emerged and the assumption was that the protein was killing brain cells.

Therefore removing amyloid beta should save brain cells and slam the brakes on Alzheimer's, experts thought.

The drug companies poured in.

Ms Evans said: "Some pharmaceutical companies were jumping on that thinking it was going to be the golden bullet, that hasn't been the case."

And they left other avenues, relatively, unexplored.

"A lot of pharmaceutical companies put all their eggs in one basket," says Ms Evans.

So is everything we know about Alzheimer's wrong?

Has science made a massive, expensive mistake? Is the "amyloid hypothesis" dead? These are questions being asked.

Prof Bart De Strooper, the director of UK Dementia Research Institute, told me: "The amyloid hypothesis as has been formulated over the last 20 years is dead, that I would accept.

"What I won't accept is that the importance of amyloid is dead."

There is a tonne of evidence that supports amyloid having a role in some dementias.

This includes genetic studies on people with familial dementia, who develop the disease in their 30s and 40s. It is caused by rare mutations in their DNA that alter the way amyloid works in the body.

Prof De Strooper says: "The genetic evidence for amyloid is so strong that it's hard to go to the other side, which says that amyloid has nothing to do with the disease.

"What we need is a new theory."

So what is amyloid doing?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe role of amyloid beta is being reimagined.

So instead of being the toxic protein that chokes nerve cells to death, it is being seen as the initial step that culminates in the dementia.

Prof Spires-Jones said: "Some people call it a trigger and once you've pulled the trigger then the bullet is on its way.

"So doing anything to the trigger is no longer an effective method."

The optimistic view is that anti-amyloid drugs may have a role in preventing Alzheimer's, but only if they are used before the disease starts.

That may be why the current Alzheimer's drug trials have failed, because people are being treated too late.

A new theory for Alzheimer's?

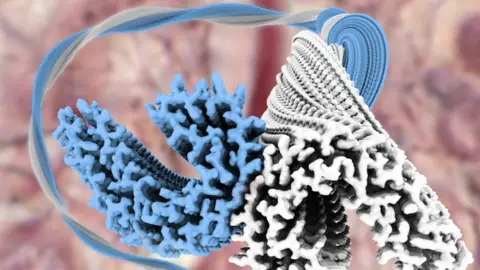

Some researchers are pinning hopes on another protein called tau.

If amyloid beta is the trigger, tau may be the bullet.

"Tau is one of my favourite proteins, where there's tau there's cell death in the brain," says Prof Spires-Jones.

"I think tau is very important for somehow causing the cells to get sick and die."

LMB

LMBHowever, again this is not 100% certain and there is no evidence in human trials that lowering levels of tau in the brain is going to stop neurones dying.

Focusing on neurones and dangerous proteins can miss the bigger picture of what is happening in the brain.

This is a lesson being learned from cancer, where understanding the role the immune system plays has led to a whole new branch of medicine - cancer immunotherapy.

The immune system is being heavily implicated in dementia too.

If you look at genetic mutations that increase the risk of developing dementia, then a good chunk of them are involved in the immune system.

While your brain is packed with neurones that do the "thinking" - they are ably assisted by special immune cells called microglia.

They do fight infections, but also keep the brain running smoothly by munching up anything that should not be there.

And the blood vessels in the brain are increasingly being seen as a key player, not just in vascular dementia, but other dementias too.

Prof De Strooper still sees abnormal proteins as the trigger, but "then you have the response of the brain on that threat".

He told the BBC: "Some people have very good genes, very strong inflammation response or a very good vascular (blood vessel) response, and they will maintain good health even while these biochemical changes are present in the brain."

And, on the flip side, some people who are genetically programmed to respond poorly would go on to develop dementia symptoms.

Prof De Strooper said: "All of a sudden, you open a broad box of possible drug targets, because you can then start to think about how do we improve the response of the brain at the inflammatory side, at the vascular side, at the neuronal side?

"That's what at this moment is happening."

Sounds like we don't know exactly what is going wrong in the brain?

Getty Images

Getty Images"Unfortunately, we don't have a full understanding," says Prof Spires-Jones.

She said there were key gaps in our knowledge:

- We don't know why the neurones are dying, we don't know the actual cause of their death

- We don't know which forms of the proteins that accumulate in the brain are toxic

- We don't really know why they accumulate in the first place, why they start where they do, why they spread through the brain, and whether it will be effective in humans to stop that process

"So there's some big questions left that we need to understand in order to effectively treat the disease," she said.

But we have switched from talking about all dementias to mostly Alzheimer's disease, where most of the medical research has been focused.

Each type of dementia has different traits, with different parts of the brain affected and different aberrant proteins building up in the brain.

For example, alpha-synuclein builds up in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia.

There may need to be different treatments targeting different proteins and confusingly some patients have "mixed dementia", with multiple diseases playing out at the same time.

Why is there such a gap in our knowledge?

There are two significant factors - one is the sheer complexity of the brain and the other is a lack of funding for research.

The human brain is the most complex structure in the known universe and is made up of 100 billion neurones.

To steal Prof de Strooper's analogy; if every person on the planet (currently around 7.5 billion) had a computer and they were all hooked up and working together - that would still be less than a tenth of what's going on inside the brain.

And yet for every single scientific study published on any form of neurodegeneration, there are 12 on cancer.

The focus has simply been elsewhere.

How good does a treatment need to be?

Less than you might think.

While completely curing all forms of dementia is the goal, there could be huge benefits from drugs that just slow the pace of a dementia.

An analysis by Alzheimer's Research UK argued a drug that delayed the onset of dementia by five years would cut the number of people living with the disease by a third.

The reason is dementia tends to be a disease of old age, and if you can buy just a little bit of time then you may well have died of other causes before your brain is affected.

Slowing the decline would also keep people living independently for longer.

Can my brain resist dementia?

SPL

SPLProf Spires-Jones said: "How resilient is the brain? It's phenomenal!"

After a stroke kills brain cells it is possible to regain some degree of lost function. But this does not come from growing new brain cells, but rewiring those that remain.

Prof Spires-Jones told the BBC: "In Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, there's a similar amount of ability of the brain to cope by changing the network."

In fact, huge amounts of damage have already been done to the brain by the time somebody is diagnosed with Alzheimer's by their family doctor.

"When you look at people at that stage, they've already lost half of the neurones in a part of the brain really important for memory, the entorhinal cortex," Prof Spires-Jones said.

But that creates a new problem - starting treatment at this stage is not going to recover those lost brain cells. You are mostly born with all the brain cells you will ever have (there are some exceptions).

Well how will treatments work then?

Let's fast forward to a world where we do have treatments and now the brain's great asset, its adaptability, is the problem as it may have masked the disease for more than a decade.

Ms Evans, from Alzheimer's Research UK, said: "There's no point halting the progression of the disease in end stage disease."

But equally it will not be practical for everybody to have a regular brain scan to catch dementia early, because those scans are incredibly expensive.

One option is the approach taken in heart disease, where millions of people take pills to lower cholesterol levels in order to stop their arteries being clogged up.

Statins lower risk before people have a medical problem.

Ms Evans said: "I think the analogy with statins is a good one.

"I think there could be something that in mid-life, you would be able to take that could then lower your risk or ensure that the development of this disease would be slow."

Prof de Strooper envisages a system of screening people that may even start at birth with a DNA test that predicts who is at greater risk.

Then regular cognitive tests throughout life would act like an early warning system for people who need a more detailed examination.

And patients who turn out to already have a diseased brain would be offered drugs that stop brain cells dying, all before symptoms emerge.

Is there anything I can do to dodge dementia?

There are no guarantees, but there are ways you can lower the odds of developing dementia.

Research estimates that one in three cases could be prevented by lifestyle changes including:

- treat hearing loss in mid-life

- spend longer in education

- don't smoke

- seek early treatment for depression

- be physically active

- avoid becoming socially isolated

- avoid high blood pressure

- don't become obese

- don't develop type 2 diabetes

It is not completely clear why these protect the brain.

Do these lifestyle factors actually stop the process of dementia in the brain?

Or do they prepare the brain for dementia by increasing the connections and flexibility of the brain so that as neurones start to die, the brain can compensate for longer and symptoms don't emerge?

On a personal level it probably doesn't matter - not getting dementia, is not getting dementia. But scientifically the questions matter as the answers will illuminate what is going on in the brain.

"People who are very healthy and take good care of themselves are the group that I would say is most resilient to Alzheimer's disease," says Prof Spires-Jones.

So is there any hope?

There is now far more money being spent on dementia research.

The optimistic view is that we are at the same point as the Aids crisis was in the 1980s, when an HIV infection was a death sentence.

But now people who get anti-viral drugs have a nearly normal life expectancy.

Prof Spires-Jones said: "We know from things like cancer, that if you do a lot of science and research into a field, you can make a huge difference and find cures and treatments for these complex diseases.

"So I think we'll get there, but we do need to understand more about the fundamental brain changes in order to come up with effective treatments."

Ms Evans said: "There are potential trials, within this year, coming to fruition, I would hope to see some positive stories out of those in the next year or two.

And Prof de Strooper expects the first treatment within a decade: "It will not cure all dementia, I think we will have to cope with that for a long time.

"But it will certainly postpone the disease, you will decay much slower, and dementia will be much less a threat for the society."

Follow James on Twitter.