Dry January: Does it lead to binge-drinking in February?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn estimated 4.2 million people in the UK said they were planning to abstain from drinking in January - and the official Dry January campaign says it's designed to "reset" people's relationship with alcohol.

So does a month off drinking help people form new habits, or is it likely to lead to a February binge?

The idea that having a "dry" month leads to heavier drinking afterwards seems to be backed up by some studies - mainly on rats.

In one study, rats were given alcohol for a period of time before having it suddenly removed. When they were then given alcohol again, the rats drank more.

Researchers weren't able to find the same effect in humans, though, when they studied US army recruits who were forced to abstain from alcohol during their initial training.

Once the recruits were able to drink again, they drank the same amount or less on average - although the heaviest drinkers at the start were the most likely to drink more after abstaining.

Both of those examples look at what might happen when you force someone to give up alcohol. But what about voluntary periods of abstinence? Is there a psychological effect involved in having chosen to do something?

In 2014, researchers at the University of Sussex teamed up with the charity Alcohol Change UK (which runs the official Dry January campaign) to measure its success, and they've produced an evaluation of the campaign each year since.

When the first study was published, the then director of the charity who launched the campaign, Emily Robinson said: "The long term effects of Dry January have previously been questioned, with people asking if a month booze-free would cause people to binge-drink once February comes around."

But, she said, no such effect had been found.

Kanawa_Studio

Kanawa_StudioThis was also the finding of the team's latest report - 800 people surveyed who ditched booze in January 2018 were, on average, still drinking less in August than they were before they started the challenge, based on units consumed and days of drinking.

Lead researcher Dr Richard de Visser said half of people surveyed drank the same amount afterwards, 40% drank less and the remaining 10% drank more than before.

Those who drank more were generally the people who didn't make it to the end of the month.

Dr de Visser found a range of other health benefits, including weight loss and improved sleep.

The problem is this study is self-selecting which means the results aren't necessarily representative of the whole population.

'Missing' people

It also had a very high drop-out rate - 2,800 people signed up to the study but by the August follow-up only 800 people remained.

The researchers tried to adjust for that by looking at who was "missing" from the final sample - more men than women dropped out, as did more of the heavier drinkers.

But while you can adjust for gender and drinking habits, it's harder to adjust for less tangible things like how generally motivated and committed someone is.

In this instance, the researchers might well have been drawing conclusions about how Dry January affects people's drinking by looking at a group of especially dedicated people - who might not reflect how the general population responds at all.

The University of Sussex is planning future research where a representative sample of the general population will be studied.

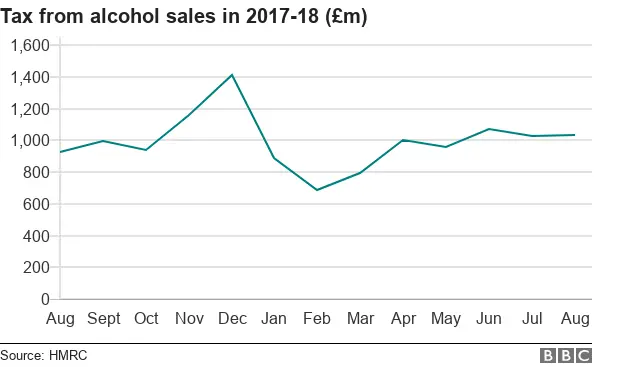

To get an idea of what's going on in the general population, we could look at alcohol sales through the year - not a perfect measure as we don't know for sure that the booze is being drunk in the same month it was purchased.

Tax figures from HM Revenue and Customs show a big spike in sales in December followed by a big fall in January. Sales continue to fall in February, before creeping back up again to pre-December levels by March.

Sales during the rest of the year are relatively consistent.

There's little dispute over the health benefits of reducing alcohol intake (although people who are alcohol-dependent should seek professional help before withdrawing). But as for whether attempting a booze-free month helps reduce people's alcohol intake overall, the evidence is still patchy.

The heaviest drinkers are the least likely to make it through the month and those who don't make it all the way through are more likely to then drink more.

But for the heaviest drinkers who do make it through, and do end up drinking less, perhaps unsurprisingly they also get most benefits.

They reduce their drinking to a greater degree and see more marked health benefits.

The University of Sussex researchers who evaluated the study caution that this challenge is not suitable for people with alcohol dependence issues.

Maddy Lawson at Alcohol Change UK said: "A month off alcohol is safe for the vast majority of people, including most heavy drinkers. But if you drink very heavily or regularly you may be physically alcohol dependent, and in this case you are likely to need more support to cut down."

For those people not in that alcohol dependent category, but who are prone to binge drinking and "binge abstaining", some experts suggest they might be better off having a couple of dry days a week throughout the year instead.