Will NHS long-term plan deliver the goods?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe have been waiting a long time for the 10-year plan for the NHS in England. Will it have a real impact? The answer has to be yes if the NHS is to have a sustainable future.

Much of the thinking is driven by the need to treat more patients in their local communities or at home.

Put simply, given that people are living longer and, as they do so, developing more chronic health problems, hospitals will be overrun unless there is more care on offer elsewhere.

The burden on the health service caused by obesity looms large.

That is why an increasing share of NHS resources in England will be directed to GP and community health services. Local schemes which have successfully joined up health and social care provision will be rolled out across England.

Prevention of ill health and quicker disease diagnosis are also central to the drive to keep people out of hospitals where appropriate.

In another sense this plan is different from its predecessor. In 2014, the chief executive of NHS England Simon Stevens set out his aims in a document named the Five Year Forward View.

Specific pledges

It was a pithy statement of the problems with a strategic vision - but it did not set out detailed plans or commitments.

By contrast, the latest plan is littered with specific pledges. Among the most eye-catching are:

- Increased early detection of cancer through better testing and giving every child diagnosed with cancer a comprehensive DNA test to determine the best way to target treatment.

- Making mental health help available to 345,000 more children and young people through community services and schools in England.

- Hospital out-patient appointments - which are often difficult to attend, and regularly missed - to be reduced in favour of phone or screen-based consultations for patients at home, and consultants going out to GP surgeries, rather than expecting patients to come to them.

Ministers seem to have realised that grand strategy does not cut much ice with patients who simply want to know how treatment of their conditions will improve.

Instead, the new plan majors on what Whitehall sources call "retail offers".

Many of the pledges, though, are over the next decade and it is not clear yet how progress will be checked.

NHS leaders have called for new legislation to allow some of their proposed changes to go ahead. This marks a symbolic break with the controversial health reforms of 2012 drawn up by the then-Health Secretary Andrew Lansley.

The Lansley reforms gave more powers to local commissioning groups allowing more tendering with outside organisations for contracts. It's understood NHS England wants legislation to allow local health and care groups to work more closely together. It argues that force of law would significantly accelerate progress on service integration, on administrative efficiency, and on public accountability.

But will the government find the legislative time to get changes through Parliament?

Staff shortages

Big unanswered questions remain.

Does the NHS have the workforce to cope with rising demand and see through service changes? Ministers and NHS leaders point to plans for training of more nurses and extra medical school places. But the current 100,000 NHS vacancies in England underline the scale of the challenge.

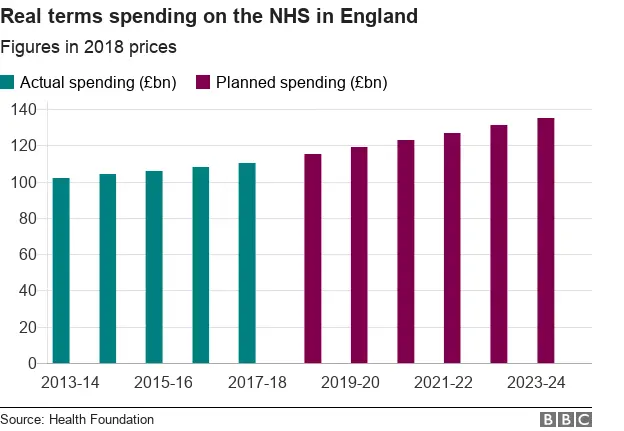

Is the new funding allocated by the government going to be sufficient to deliver all the new commitments, as well as keep up with patient demand? The 3.4% real terms annual increases in funding for the next five years are no more than the long term average for the NHS, albeit more than under the coalition and Conservative governments. Significant efficiency savings will need to be made to free up resources to invest in the transformation of services.

Then there is the thorny issue of targets. Simon Stevens has made clear he wants to amend the main A&E target of 95% of patients being admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours. He and some medical leaders want to see different benchmarks for major and minor injuries.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome doctors feel that would be a mistake and it may prove politically difficult with accusations that the goalposts are being shifted. The final tricky decision will rest with ministers.

Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland will gain extra funding through the usual formula but the devolved administrations will decide how it is spent.

Around the UK there are the same challenges - an ageing population with sicker patients and finite resources.

Wales drew up its long plan last year. Now NHS England has done the same. We now must wait to see if they withstand the test of time and rising demand for care.