Six key questions Brexit poses for the NHS

Whether it is a no-deal Brexit or the agreement brokered by the prime minister, leaving the European Union promises to have a profound impact on patients and the wider NHS.

From the staff who work on the wards and in the GP surgeries to the supply of vital medicines, there are implications.

Here is a look at six key questions.

Will we run out of medicines?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK imports 37 million packs of medicine each month from the EU - although it exports even more.

The port of Dover is the key supply route in and the transition arrangements mean it will remain unaffected.

The key challenge will be if there is a no-deal Brexit, because there is concern of potential huge delays at the port.

The government has asked firms to stockpile a six-week supply of drugs to mitigate any problems if there is no deal.

However, that is logistically difficult for medicines that need refrigerating, like insulin and vaccines, or those with a short shelf life, such as some cancer drugs.

Supplies of radioactive materials for scans could also be hit.

Contingency plans have been put in place to fly in vital treatments, the government has said.

But even the stockpiling of normal medicines is proving problematic, according to industry.

Small firms in particular have reported problems stockpiling drugs because they do not have the cash flows to fund reserves of supplies.

Last month, Martin Sawer, of the Healthcare Distributors Association, told the Health Select Committee that he was "very concerned" about the prospect of a no deal, saying it could have "catastrophic" consequences for the supply of drugs.

He even suggested the public may have to stockpile drugs themselves.

The government has always insisted this is not needed - and could in fact make the situation worse.

Only this week, Health Secretary Matt Hancock was telling MPs that while a no-deal scenario would be "difficult", he was "confident that if everyone does everything they need to do, then we will have an unhindered supply of medicines".

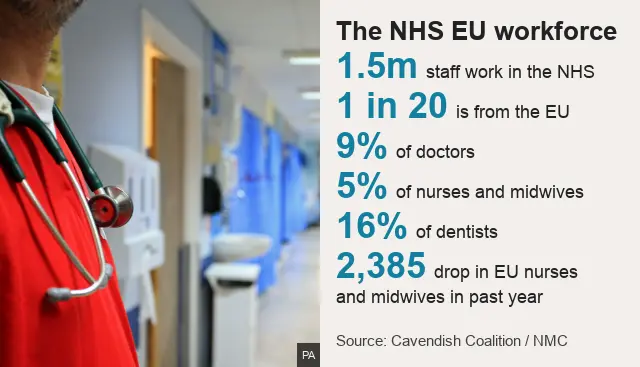

Will we have enough staff?

The health and social care sectors are huge employers with one-and-a-half million and two million staff respectively. About 5% of the registered workforce in each area are from Europe.

The Brexit agreement means all those currently working will have the opportunity to obtain "settled status" to allow them to stay.

It is not clear what a no-deal Brexit would mean.

The government has also indicated it will create a skilled migrants system similar to the one that operates for workers from the rest of the world. That system - known as tier two visas - allows doctors and senior nurses to be recruited from overseas.

But unions have pointed out that some lower-paid nurses and non-clinical staff such as health care assistants, porters and care workers will not be covered by such a system, because the cut-off is that the worker must be earning at least £30,000 a year.

There are other related factors too.

The message Brexit sends to people from Europe and the weaker value of the pound, which means any money sent back to their homeland is worth less, could put off people from working in the UK.

That is a point made last month by the Cavendish Coalition, a group of 36 health and care charities.

It predicted Brexit could worsen the staffing shortages currently being seen in the health service.

The government is more confident, arguing staff from Europe will stay and that it has a plan to "grow its own", with increasing numbers of doctors and nurses in training.

What about our health insurance cards?

Alamy

AlamyAbout 27 million people in the UK have European Health Insurance Cards.

They entitle the holder to state-provided medical treatment across the EU and also in Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland.

The cards cover pre-existing medical conditions as well as emergency care.

This will continue during the transition period, but, like much else, what happens afterwards has yet to be resolved.

And if there is a no deal, the cover EHIC provides will cease to exist in theory.

Attempts could be made to put reciprocal agreements in place - and given the amount of tourism into the UK from Europe it would clearly be in everyone's interest to ensure individuals are entitled to health care.

Then there are the one million UK citizens who live abroad in the EU.

They are currently eligible for the same health care as citizens of the EU country in which they live and they can use EHIC when they travel.

The EU and UK have agreed that these people would retain their rights, but once again a no-deal Brexit could scupper that.

Could medical research lose out?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK is considered a world leader in medical research, having produced around 25 of the top 100 prescription treatments.

The country currently benefits from access to research funding from the EU via programmes such as Horizon 2020 and the Innovative Medicines Initiative.

These will continue during the transition phase, but beyond that it seems likely the UK will be treated as a third-party collaborator, meaning it will be less likely to lead programmes and will have little role in the design of them.

Collaboration on rare diseases could also be put at risk. As the number of patients with rare conditions in each country is low, it is only possible to recruit enough patients for clinical trials by carrying out those trials across countries, according to the Brexit Health Alliance.

Restrictions to the free movement of researchers and academics could also have an impact. Around three-quarters of UK researchers have worked abroad and currently nearly a fifth of science, technology, engineering and mathematics academics at UK institutions are from the EU.

The government believes a "mutually beneficial outcome" is perfectly possible to deal with all these problems, given the UK is such a key player in medical and scientific research.

The government is also increasing its spending on research and development.

What is the impact of EU migration on NHS demand?

SPL

SPLClearly, the NHS is struggling to cope with the number of patients it is seeing.

The three key waiting time targets for cancer, A&E and hospital operations are being missed in every part of the UK.

The public does believe migrants are a factor in this - or at least the wider demand on services.

In 2017 an Ipsos opinion poll found 58% of people in the UK agreed with the view that immigration placed pressure on public services.

The government's Migration Advisory Committee looked at this in the autumn.

Its report found migrants were net contributors to the health service - in that they gave more than they took.

That is because of the significant numbers working in the health service and the fact they were less likely to use it.

The committee said this was because they tended to be young and healthy.

The only exception was in maternity care, the committee said.

The proportion of births to mothers from the EU has trebled in the past 15 years to one in 10.

What about the £350m Brexit dividend?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was one of the most controversial claims of the referendum campaign.

Vote Leave said the money saved in payments to the EU would mean an extra £350m a week could be spent on the NHS.

The prime minister has claimed this has come true. Over the summer she announced the NHS budget would increase by £20bn by 2023.

On top of that, about £4bn will be given to the rest of the UK.

That amounts to more than the promised £350m a week.

Theresa May has said it will be partly paid for by a Brexit "dividend".

Although, as the UK is committed to paying into the EU budget until the end of the transition period and will also have to pay the £39bn divorce bill, it arguably leaves little to cover the cost of the rise.

The Treasury has said a combination of economic growth and perhaps even tax rises may be needed.

Another way to look at it is to ask whether the NHS would have got such a rise if Brexit was not on the cards?

Many think so. After all, it was long overdue.

Since 2010 the NHS has been receiving between 1% to 2% extra each year - half the average rises it previously enjoyed.