Why the world needs to get ready for more people dying

For decades, lifespans have grown ever longer, delaying the inevitable fact of death. But the coming years will see a sharp rise in the number of people dying, presenting a challenge about how we care for those at the end of life.

We started the 20th Century without penicillin, but now genomic medicine raises the possibility of increasingly sophisticated treatments tailored to an individual's genetics.

In little more than a century, medical and scientific breakthroughs like these have seen life expectancy increase dramatically - by about 30 years, to 79 for men and 83 for women in England, for example.

Death had been an unpredictable event: most people died suddenly, often from infectious diseases.

Now, infectious diseases that were once fatal are curable, improved survival rates mean many people live for years with cancer, while dementia has become the most common cause of death in England and Wales.

We are living longer and dying slower, but how well prepared are we for the challenges that come with that?

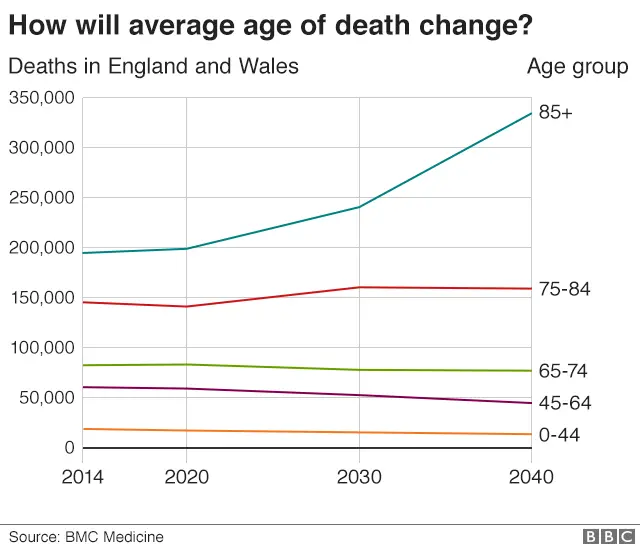

A central challenge is presented by the fact that we are going to have to prepare for many more deaths.

As lifespans increased - and individuals delayed dying - the number of deaths decreased.

But everyone has to die and we are now at a tipping point.

In England, for example, there are currently around half a million deaths each year.

This will increase by about 20% in total over the next 20 years, until an extra 100,000 people are dying each year.

Worldwide, the pattern is similar.

The World Health Organization estimates that the number of deaths worldwide will rise from 56 million in 2015, to 70 million in 2030.

This rise will mainly be caused by an increase in non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and cancer.

This is illustrative of a second challenge: most people will suffer from multiple medical problems in their final years. They will experience a gradual physical - and often cognitive - decline before they die.

So, how can we best care for these people?

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life for people approaching the end of their life.

Working in teams including nurses, social workers, counsellors and chaplains, palliative care specialists identify the worst problems for patients with terminal, or life-limiting illnesses and aim to improve these symptoms.

Many will be experiencing physical symptoms such as pain, nausea, or breathlessness. For others, the greatest problems may be psychological, social or spiritual.

Research suggests that palliative care can significantly improve quality of life - with people experiencing fewer physical symptoms and reduced rates of depression. They also have a greater chance of dying outside hospital.

Historically, palliative care was used after all other medical options had been exhausted, but we now know that it works best when used early and alongside other medical care.

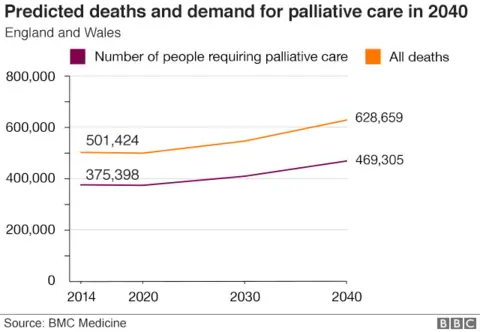

Worldwide, more than 20 million people are estimated to need palliative care at the end of life each year. In high-income countries, as many as eight out of 10 of those who die are thought to need such treatment.

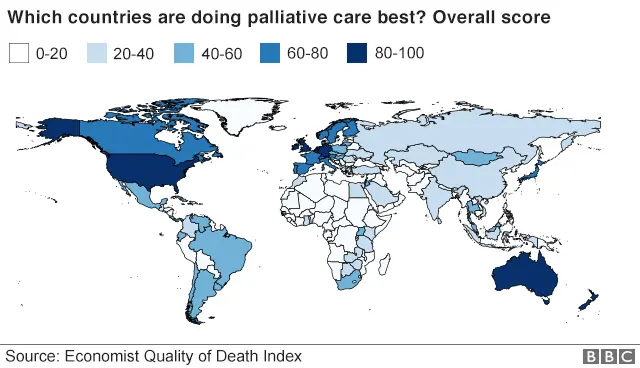

Generally speaking, richer nations tend to offer the best end of life care, with the UK placed first on the two occasions that the Economist Intelligence Unit published global rankings.

However, some less wealthy countries such as Uganda, Mongolia and Panama have also demonstrated rapidly improving standards of palliative care, through a combination of national policies, public campaigns and strong leadership from advocates.

This is important, as it is thought that eight out of 10 people dying with a need for palliative care live in low and middle income countries.

Palliative care and the hospice movement

- The modern hospice movement was started by Dame Cicely Saunders in 1967

- Palliative care is most effective when offered alongside other medical treatments

- It can improve people's quality - and sometimes quantity - of life

- Hospices are for those with any life-limiting condition - not only cancer

- Hospices are not only about death - many people will be discharged

- Palliative care specialists see people in hospitals, care homes and their own homes

But challenges remain if palliative care is to be made available to all those who need it, particularly as the number of people dying increases.

For example, access to opioid painkillers is a key indicator of the quality of end of life care.

Drugs such as morphine are relatively inexpensive, but access can be hampered by legal restrictions that aim to prevent abuse.

Opioids were freely available and accessible in only 33 of 80 countries studied for the 2015 Economist Intelligence Unit report.

But things are changing.

In Colombia, a 2014 law ensured availability of opioids.

In Uganda, public awareness campaigns, as well as legal changes, have helped promote use of opioids at the end of life.

Further challenges are found around funding.

This is a particular issue in poorer countries, where even basic research on symptoms in advanced disease and how to treat them can be lacking.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven in high-income countries, research funding is limited.

In England less than 0.5% of the medical research budget is allocated to palliative and end of life care research, at a time when demand for palliative care is expected to rise by up to 40% by 2040.

Dementia will be a major driver of this and improving community care for people with the condition could reduce reliance on emergency care.

Improving end of life care is a global challenge, made more urgent by ageing populations.

Medical and scientific progress over the past decades has changed how we die.

But it has not changed the fact that it will happen to all of us.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Katherine Sleeman is an NIHR Clinician Scientist in palliative medicine at the Cicely Saunders Institute, King's College London. Follow her @kesleeman

The Cicely Saunders Institute is a purpose-built institute for palliative care, combining research, education and clinical care.

Edited by Duncan Walker