How Amsterdam is reducing child obesity

Childhood obesity rates are rising in many parts of the world - but in Amsterdam they are falling. The city's healthy-weight programme has seen a 12% drop in overweight and obese children.

"Go!" shouts the instructor. Tyrell van der Wees throws himself forward to do sit-ups, then jumps up and runs to the end of the gym and back again. He is breathing fast, his heart pumping.

The nine-year-old is smiling, working hard and having fun. He is also part of Amsterdam's efforts to improve the health of its children.

At the back of the gym Tyrell's mother, Janice, is sitting with other parents watching the fitness class.

"He's really happy. He is doing something to improve his health. He knows the consequences and he is trying to do something about it," she says.

A year ago Tyrell's school told Janice he was overweight. Children in Amsterdam are now regularly weighed and tested for agility and balance.

Tyrell was referred to a child health nurse, Kristel de Lijster.

She offered them a package of help including dietary advice, joining a gym class and a volunteer to make home visits - all for free.

In a health centre in south-east Amsterdam, Kristel de Lijster explains how she helps families such as Tyrell's.

"The most important thing is not to communicate in a standard way, because everybody already knows eating sugar and eating fast food is unhealthy," she says.

"You really want to communicate the message on the level the parent and the child understands.

"So, when the child is overweight it is more important for them to tell you what they think is going wrong."

In Tyrell's case, Janice thinks he was snacking on unhealthy food and playing computer games after school before she returned home from work.

At Tyrell's flat, Daniphra Millerson has come to pay a visit. She is Tyrell's "buddy", part of a volunteer network helping families towards healthier lifestyles.

She makes weekly visits. She has also taken Tyrell to the supermarket to look at healthier food choices and introduced him to some after-school activities.

He now plays tennis, goes to gym class and is much more active.

"It's working. It's really working," says Janice. She is delighted with the range of help available for her son.

"I am really happy that all that support is there from the city so we can make use of it. I wish I had known this before," she says.

Immigrant communities

Amsterdam's childhood obesity problem is concentrated in the poorer parts of the city, among immigrant communities from Surinam, North Africa and Turkey.

It is here the city's healthy-weight programme targets its resources. And it is here the fall in obesity has been greatest.

Between 2012 and 2015 the percentage of children who were overweight fell from 21% to 18.5%, resulting in a 12% drop in the total number of overweight children.

The city authorities are cautious about the findings, but the trend is encouraging.

At a community centre in north Amsterdam, women are chopping vegetables and cooking chicken soup. Most are from Morocco, Syria or West Africa. A dietician is with them giving advice on healthier cooking.

"Obesity is a problem in Amsterdam so it is urgent to work on this," says Fatima Ouahou, a community organiser.

"The women are the ones who buy and cook the food, so we want them to be the example and spread the message on healthy eating."

Amsterdam's healthy-weight programme's budget is less than €6m (£5.3m) a year.

Rather than hiring new staff, it works with existing professionals including teachers, nurses, social workers and community leaders to get across a consistent healthy lifestyle message.

"We have managed to build a whole systems approach in Amsterdam," says Karen den Hertog, deputy programme manager.

"In the everyday life of children and their parents, we manage to get the healthy message across and help people have a healthier lifestyle.

"Once we decided what the message was, we were surprised by the enthusiasm from all our partners - youth workers, schools, teachers, doctors and nurses.

"All are using the same message. We hear back from children that it's good they get the same message."

Much of the budget goes into supporting Jump-In primary schools, which allow only fruit, water and healthy food in school and encourage exercise.

It was here they faced some early obstacles from parental opposition. However, complaints soon faded, says Pascal Reit, head teacher of Pro Rege School.

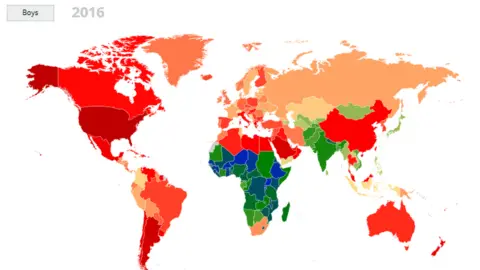

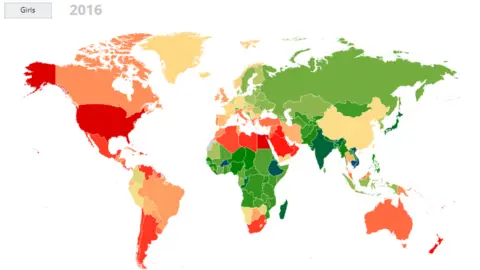

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration NCD Risk Factor Collaboration

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration"There has been some protest from some parents who think we should not be telling them how to raise their children. Now everyone accepts it. There is no problem any more," she says.

To keep its healthy message consistent, the city has banned junk food companies from advertising on the subway or sponsoring sporting events. It is also working with shops and supermarkets to promote fresh food.

All political parties back the programme, and this consensus helps the programme take a long-term approach towards healthier lifestyles.