NHS 'haemorrhaging' nurses as 33,000 leave each year

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe NHS is "haemorrhaging" nurses with one in 10 now leaving the NHS in England each year, figures show.

More than 33,000 walked away last year, piling pressure on understaffed hospitals and community services.

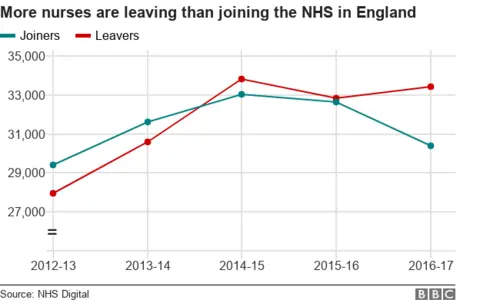

The figures - obtained by the BBC from NHS Digital - represent a rise of 20% since 2012-13, and mean there are now more leavers than joiners.

Nurse leaders said it was a "dangerous and downward spiral", but NHS bosses said the problem was being tackled.

The figures have been compiled as part of an in-depth look at nursing by the BBC.

We can reveal:

- More than 10% of the nursing workforce have left NHS employment in each of the past three years

- The number of leavers would be enough to staff more than 20 average-sized hospital trusts

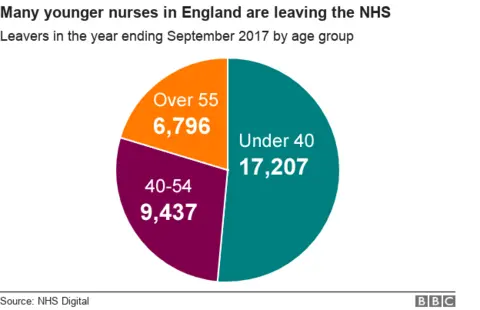

- More than half of those who walked away in the last year were under the age of 40

- Leavers outnumbered joiners by 3,000 last year, the biggest gap over the five-year period examined by the BBC

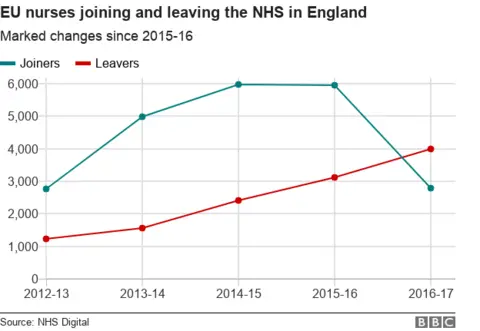

- Brexit may have had an impact. Since the referendum the NHS has gone from EU joiners outnumbering leavers to the reverse - more leavers than joiners

- Nurses are being pulled off research work, special projects and admin roles to plug the gaps

Other parts of the UK are also experiencing problems retaining nurses.

In Northern Ireland and Scotland, the leaver rates are rising. In the most recent years, 7.5% of nurses left NHS employment in Northern Ireland and 7.2% did so in Scotland. But in both nations, the number of joiners outnumbered leavers.

In Wales there were more leavers than joiners, according to Freedom of Information reports.

'I can't work in the NHS any more'

One of the nurses who has left the NHS is Mary Trevelyan.

She was working as a staff nurse in a London hospital, but quit last year after the pressures of the job left her stressed and depressed.

She had only worked in the NHS for two-and-a-half years.

"I want to be a great nurse and I want to give my patients my best, but I feel that I can't do that at the moment because we're just too short-staffed, too busy, there are far too many things for us to be doing.

"I want to work for the NHS, it's such a brilliant thing, [but] I don't think I can."

She is now living with her family in Cornwall. She says she has not decided what to do next, but is considering moving abroad.

"A few of my friends have gone. I think they've just got a better quality of life nursing overseas, which is very sad."

Where are the nurses going?

The figures do not show where these nurses went, although the BBC has been told the private sector, including agencies, drug firms and hospitals, is particularly popular.

But the figures will also include those moving abroad or leaving nursing altogether to pursue other careers.

A fifth of leavers in the past year were over 55 - the age at which nurses can start retiring on a full pension.

Royal College of Nursing head Janet Davies said: "The government must lift the NHS out of this dangerous and downward spiral.

"We are haemorrhaging nurses at precisely the time when demand has never been higher.

"The next generation of British nurses aren't coming through just as the most experienced nurses are becoming demoralised and leaving."

She said nurses needed a pay rise and more support if the vacancy rate - currently running at one in nine posts - was not to increase further.

"Most patient care is given by NHS nurses and each time the strain ratchets up again they are the ones who bear the brunt of it," she added.

It also says more must be done to support younger nurses at the start of their careers.

The chief nursing officer for England, professor Jane Cummings, admitted there was a problem - but said changes were being made to highlight the value of the NHS to new talent and retain current staff.

"We do lose people that need to be encouraged. We're in the process of bringing in lots of nurse ambassadors that are going to be able to talk about what a great role it is, to be able to tell their story, so we can really encourage people to enter the profession and for those in the profession, to stay in it," she said.

How the NHS is trying to stop the exodus

The regulator, NHS Improvement, is rolling out a retention programme to help the health service reduce the number of leavers.

More than half of hospitals and all mental health trusts are getting direct support.

Master classes are also being organised for all directors of nursing and HR leads.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryThe support is prompting hospitals to adopt a range of initiatives.

Some have introduced internal "transfer" systems, allowing nurses to move jobs more easily, and mentoring schemes have been started for newly qualified nurses, while in some places, staff can ask for "itchy feet" interviews where they get the opportunity to talk to bosses about why they might leave.

Others have introduced staff awards and worked with local businesses to offer workers discounts and benefits at shops and gyms.

England's chief nurse Prof Jane Cummings acknowledged there was a "workforce problem" and it was becoming more of a challenge retaining nurses.

But she said the NHS was learning by making nursing more attractive.

"We are beginning to see some fantastic good practice giving people flexible, rewarding careers. The key is getting it everywhere."

She also said in the future the number of joiners should rise.

The government is increasing the number of nurse training places by 5,000 this year - a rise of 25%.

But it will be three years before these nurses graduate.

Does the leaver rate matter?

The Department of Health and Social Care in England has been quick to point out that the number of nurses employed by the NHS has risen.

They have picked May 2010 - the point when the coalition government was formed - as the starting point, claiming there are "11,700 more nurses on our wards".

That relates to the rise in hospital nurses - up from 162,500 full-time equivalents.

But if you look at the entire nursing workforce, the numbers have only risen by just under 3,000 to 283,853 on the latest count - a rise of 1%.

The population will have grown by 5% during this period, according to the Office for National Statistics.

And if you look at nearly any measure of NHS demand - from GP referrals and diagnostic tests to emergency admissions and A&E visits - the increase is somewhere between 10% and 20%.

What is more, if you take the last 12 months, the number of nurses has started falling and the number of vacant posts is rising.

Even taking into account the rising number of nurses in training, the health service will only be able to ensure it has enough nurses by tackling retention.