Personality disorder patients 'let down' by system

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is a medical disorder that cuts life expectancy by almost 20 years, according to the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP), afflicts more people than cancer and costs the country around £11bn a year.

But most of us know next to nothing about it. Some question whether the illness even exists.

Campaigners say Personality Disorder (PD) is the Cinderella diagnosis of the NHS's Cinderella mental health services. There is certainly no fairytale ending for those unable to access treatment and support. Health professionals who are demanding better access to treatment for those affected say one in 10 people diagnosed with it ends up taking their own life.

A consensus statement signed by the RCP, the Royal College of Nursing, mental health charities, professionals and those with experience of PD has been launched in Parliament demanding improvement to the "appalling treatment" sufferers receive.

While there has been focus recently on improving NHS treatment for psychosis, anxiety and depression, leading voices in mental health say far too little evidence-based treatment is available for the more than 3 million people, according to the RCP, whose lives are being ripped apart by PD.

In addition, the RCP estimates at least one person in 20 is living with a personality disorder right now.

Often triggered by some emotional trauma in childhood, among the more common features of PD are self-harm, substance misuse, abrupt mood swings and suicidal thoughts.

A number of different types have been identified but all involve persistent emotional instability and behaviour that has a profoundly negative impact on people's lives. In Sheffield, I met PD sufferer Catherine Carlick.

"Imagine you are on a rollercoaster that's going up and down, up and down. It is like that for me. My mood is up and down, the voices in my head, the impulsivity, the anxiety, the intrusive thoughts that you have. Every day can be a case of getting through that day."

Walking with her two beloved dogs near her Sheffield home, Catherine comes across as bubbly and confident.

But beneath the cheerful surface is a woman tortured since childhood by what she has now been told is Borderline Personality Disorder - so-called because its symptoms are on the borderline between psychosis (an impaired relationship with reality) and neurosis (anxiety, depression and obsessive behaviour).

Whatever the label, the disorder's impact can be devastating.

"I saw bar codes at the back of my victim's neck that were sending messages to me telling me to poison her."

Catherine's PD involved hearing voices which convinced her to try to poison a work colleague.

"I put diazepam in her drinks thinking she would go off work poorly and get the sack," Catherine tells me. "She had to be removed from the situation."

She was sent to prison before being moved to a secure psychiatric unit where she was eventually diagnosed with PD.

"It's one of the darkest places in my head I have ever been, I would prefer death to that. Anytime I would prefer death to the way I felt."

Most PD sufferers are not offenders, but in the last decade it is the criminal justice system that has given impetus to the diagnosis and treatment of PD. It is estimated that 70% of prisoners have the disorder.

Today there are a number of psychological therapies approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that help some sufferers manage their condition.

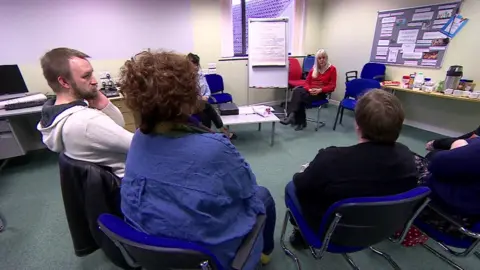

Sarah Rose is among a group of people with PD who attend a therapy session in a GP surgery in Swindon.

The treatment helps them manage their thinking more effectively, providing mental escape routes when emotions threaten to become damaging or potentially catastrophic.

"The stress I experience triggers emotions and automatically I just want to kill myself. Now I know that there is something I can do before that," she explains.

"It's been a lifetime of trauma, sexual abuse, rape, that brought me to literally caving in and thinking what the hell is going on," reveals one woman. "Coming here - it's saved my life", says another. "Coming to a (PD) group like this, you are not alone," another woman explains. "The label isn't helpful but there are commonalities."

The Personality Disorder label divides campaigners. For some, it is useful as a rallying point for services, support and campaigning. For others, it serves to deepen the stigma.

There are numerous stories of people with a PD diagnosis being excluded from services, seen as a difficult person rather than someone in desperate need of help. The phrase is often wrongly aligned with violence and criminal behaviour.

Brain scans of people diagnosed with PD suggest differences from those in the wider population.

"My name is Sue Sibbald and my personality is not disordered." Sue is diagnosed with PD but thinks the term increases prejudice. She now runs family therapy sessions in Sheffield and campaigns for more access to treatment.

"We have 25 people booked on a course every month. GPs are screaming out for help but there is nowhere to send people. Recently, sadly, someone I knew died by suicide as she was kept out of a service."

Services for people with personality disorder are better than they were, but provision is piecemeal. For some, the consequences can be fatal.

"People are waiting months for treatment, turning up at A and E, and not getting the help they need, and these people are dying waiting," Catherine Carlick tells me.

"A lot of my friends have killed themselves. I have lost four or five friends within the last two years. Therapy has turned my life around, it gave me the help I needed. Some people are not as lucky as me but it shouldn't be about luck."

NHS England says getting people the help they need, close to home, is at the heart of their plans. "Personality disorders are rooted in problems during childhood, so whilst our £1bn investment in young people's services is crucial, there is also a significant role for other public services, local authorities and the justice system to play in tackling the complex causes and symptoms of these conditions."

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by mental health issues, these organisations may be able to help.

Details of organisations offering information and support with mental health are also available at www.bbc.co.uk/actionline, or you can call for free, at any time to hear recorded information on 08000 564 756.