10 charts that show why the NHS is in trouble

PA

PAThis month hospitals have reported huge pressures, with A&Es over-crowded, a lack of beds and queues of ambulances stacked up outside unable to hand over their patients.

It was a similar story last winter. The NHS, it seems, is always facing unrelenting pressure. But why is this when funding is rising?

The sheer scale of the health service can take the breath away. Every 24 hours it sees one million patients, and with 1.7 million staff it's the fifth biggest employer in the world.

So it should come as no surprise that this vast enterprise absorbs eye-watering amounts of money.

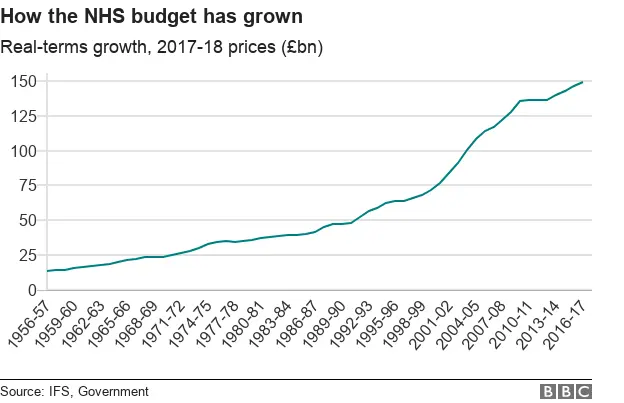

1. We spend more on the NHS than ever before

Last year in excess of £140bn was spent on health across the UK - more than 10 times the figure that was ploughed in 60 years ago.

And that's after you adjust it for inflation.

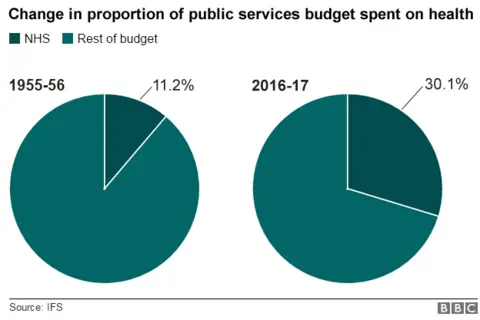

2. A bigger proportion of public spending goes on health

Governments over the years have had to invest more and more of the public purse into it. Today 30p out of every £1 spent on services goes on health.

Even during years of deep austerity in the UK, extra money has been found for the health service - £8bn more this parliament in England alone.

Yet it seems no matter how much is invested, it's still not enough. The NHS is creaking at the seams.

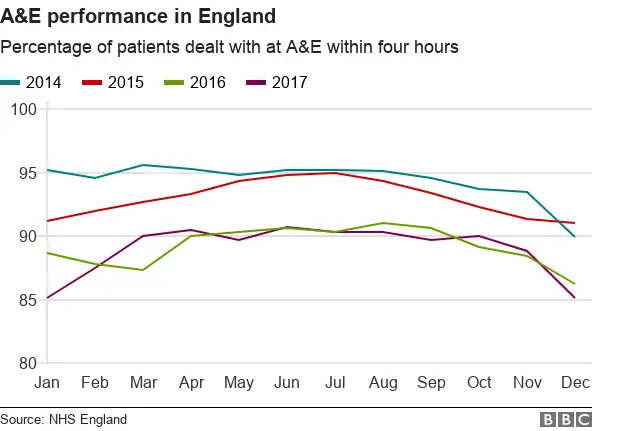

3. Key A&E targets are being missed

The best barometer of this is the four-hour A&E target. We often think of it as an indication of how good an emergency department is. But it's not. It doesn't tell you about the quality of care - how quickly you get pain relief or whether the unit is good at spotting the signs of a heart attack.

Instead it's a sign of whether the system is under stress - both in the community and in the hospital.

When there's perfect harmony between the numbers arriving and leaving, 95% of patients will be dealt with in four hours.

But this isn't happening. You have to go back to the summer of 2015 for the last time it was met in England, with performance deteriorating markedly year on year.

The rest of the UK is not immune either. Four-hour performance is worse in Wales and Northern Ireland. Scotland is performing a little better, but is still some way short of the target - its major hospitals have been hovering below the 90% mark in recent weeks.

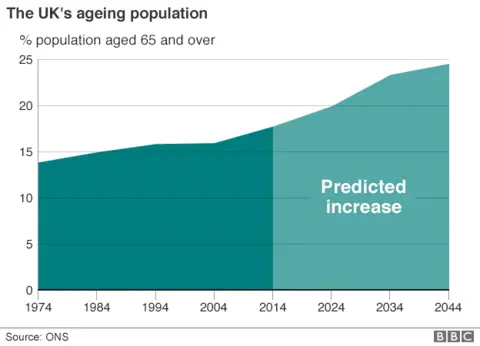

4. The UK's population is ageing

The ageing population is certainly a major factor - and it's one that all health systems in the world are struggling with. Medical advances have meant that people are living longer. When the NHS was created, life expectancy was 13 years shorter than it is now.

This is something to celebrate. Infectious diseases are no longer a significant threat. Heart attacks do not claim the lives of people early in the same numbers. Even cancer is not the death sentence it once was - half of people now survive for a decade or more.

But this progress has come at a cost. People are living with a growing number of long-term chronic conditions - diabetes, heart disease and dementia. These are more about care than cure - what patients usually need is support. By the age of 65, most people will have at least one of these illnesses. By 75 they will have two.

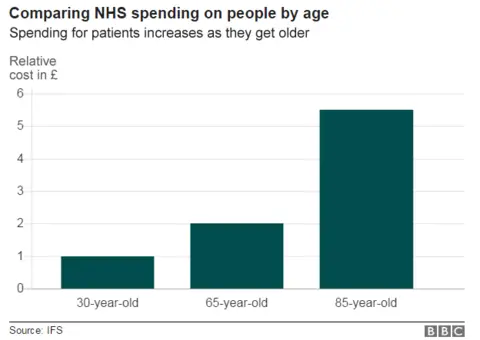

5. Care for older people costs much more

The average 65-year-old costs the NHS 2.5 times more than the average 30-year-old. An 85-year-old costs more than five times as much.

As the numbers continue to rise so does the cost to the NHS. This is compounded by the rising cost of new drugs. The health service is currently considering capping the amount it will pay for new drugs at £20m each a year. A fifth of new treatments coming on stream cost more than this.

Then there's obesity. A third of adults are so overweight they are risking their health significantly.

All this contributes to what health economists call health inflation - the idea that the cost of providing care outstrips the normal rise in the cost of living across the economy.

This is why health has tended to get more generous rises than other areas of government spending.

Over the years this has been achievable through a combination of economic growth, which brings in more money through tax, and reducing spending in areas such as defence, which has led to the NHS taking an ever-greater share of the public purse.

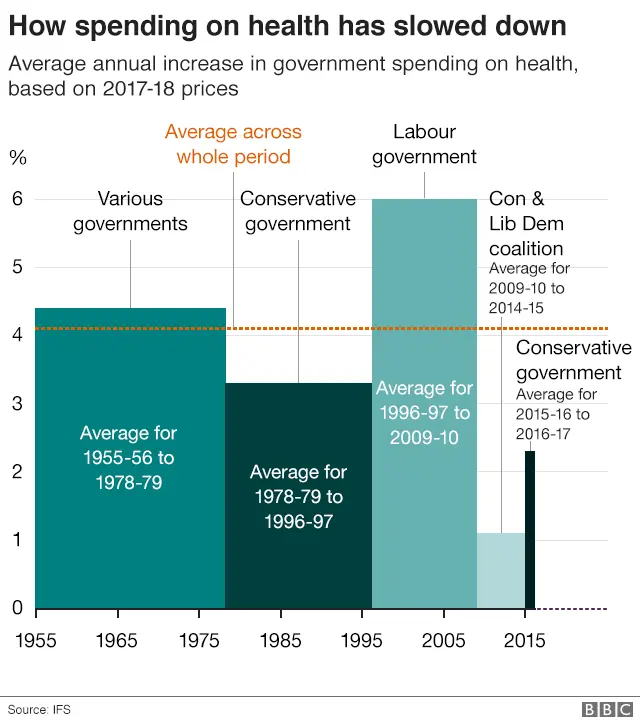

6. Increases in NHS spending have slowed

But, of course, the economy goes through cycles and over the years governments have varied the amount they were willing or able to give.

Since the NHS was created in 1948, the average annual rise has been just over 4%. During the Labour years under Blair and Brown this was considerably higher.

As you can see the period between 2010 and 2015 saw the tightest financial settlement.

The following two years were a little more generous, but that average is likely to drop a little over the rest of the parliament under current spending plans.

So ministers in England are right to say they are increasing funding - it's been frozen in Wales and Scotland - but it's just that it doesn't compare favourably with what the NHS has traditionally got.

Indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has suggested that over the 10 years to 2020, the NHS budget across the UK will not have increased enough to keep pace with the ageing and growing population.

7. The UK spends a lower proportion on health than other EU countries

But is it just a matter of more money? Would an extra few billion make all the problems go away? If you look at other European nations the UK is certainly spending less as a proportion of GDP, which is a measure of the size of the economy.

The result, as you would expect, is fewer beds, doctors and nurses per patient in the UK than the big spenders.

But a number of these countries achieve that by taxing more. Would the UK public stomach that? If a poll by Ipsos MORI for the BBC last year is anything to go by, they are pretty split - 40% would back a rise in income tax and 53% would support National Insurance going up.

Nor does it seem there's appetite for a change in the system. A majority were against charging for services or moving to an insurance-based model like some of our European neighbours do.

But even if more money was spent or raised, that would not lead to an overnight improvement. More doctors and nurses would need training and that takes time and, crucially, there is not a flood of people wanting to work in key posts.

Trainee posts for GPs are being increased, but the NHS cannot fill them all.

There also remain big questions over whether the structure of the NHS is right for 21st Century healthcare.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe NHS is still centred on the network of district general hospitals that emerged during the hospital building boom of the 1960s.

But in an era where people are struggling with those chronic illnesses, what they really need is support in the community.

The problem is there's a serious shortage of this. The number of district nurses in England has been cut by 28% in the past five years, while getting a GP appointment is becoming increasingly difficult.

8. Demand for A&E is rising

The result is that people end up going to hospital. The numbers visiting A&E have risen by over 40% in 13 years.

Not all of this is down to people with these chronic conditions, but they tend to be the cases that take the most care. Two-thirds of hospitals beds are occupied by the one-third of the population with a long-term condition.

There are attempts to change this by placing more emphasis on care outside hospital.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens has set out a five-year plan to create more integrated care, which involves hospital services working more closely with their local community teams. Similar moves are being made in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

There also an emphasis on prevention - getting people to be more active, eat better diets and drink less.

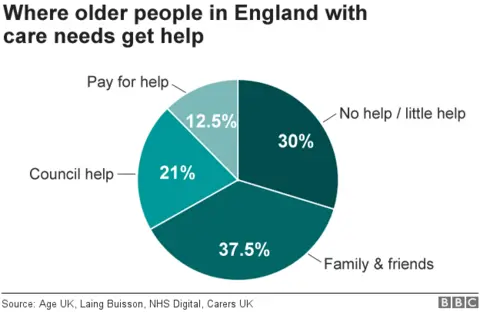

9. Fewer older people are getting help with social care

But perhaps the biggest problem is council-run social care. This encompasses day centres, help in the home for tasks such as washing and dressing, and good quality care in care homes during the final years of life. It is seen as essential to keep people well and living independently - and out of hospital.

In an era when the population is ageing you would expect more people to be getting help from the state.

However, the opposite is true. In England over the past four years for which we have data, the number of older people getting help has fallen by a quarter. The result is large numbers going without care or having to pay for it themselves.

The other parts of the UK can make a case for being more generous in this respect - home care is capped at £70 a week in Wales and free for the over-75s in Northern Ireland, while Scotland provides free personal care (washing and dressing) in both care homes and people's own homes.

Ministers in England have promised the system will change. New plans are due to be published by the summer of 2018.

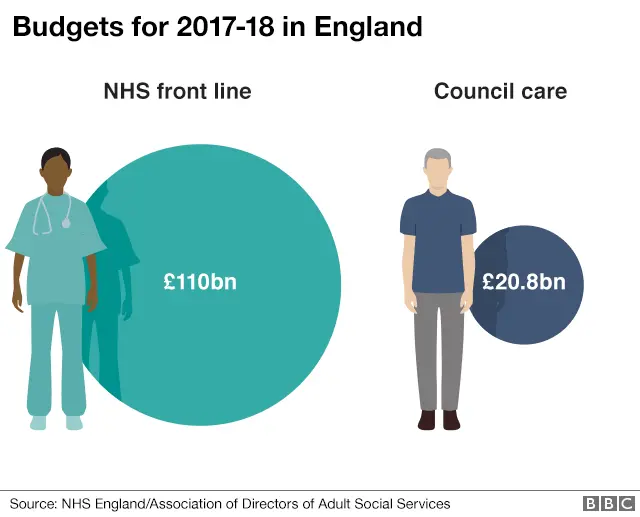

10. Much more is spent on front-line healthcare than social care

But, as yet, no part of the UK has cracked it. Indeed, if you were setting up a health and care service today, ask yourself this - how would it be done?

Would you separate medical care from personal care? Give one service to a national institution and the other to local councils? Would you provide one free at the point of need and charge for the other? Would you increase the budget of one, but cut the other?

Would you build more than 200 hospitals and spend over half of your budget on them when the biggest users of care are people with long-term illnesses that need care rather than medical intervention?

But as that is the system we have got at a time when money is limited, we are falling back on a typical British trait - making do.

Additional research: Ben Butcher