Loyle Carner: The secrets of the rapper's powerful and personal Glastonbury set

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBC

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBCIf you watched Loyle Carner headlining Glastonbury's West Holts stage on Saturday you saw something special.

Competing with Guns N' Roses and Lana Del Rey, the London rapper, 28, pulled in an adoring crowd for a soul-bearing and personally purifying performance.

"I'm playing this off like it isn't the craziest night of my life," he said.

"Thanks for being here with me, you could have been anywhere."

The show was largely constructed around his third album, Hugo, which takes a broad look at his relationship with his biological father, his identity as a mixed-race young man growing up in south London, and the scourge of knife crime that's afflicted the capital.

It was inspired by the birth of his own son, now three - who, he proudly noted, was in the crowd - and how that forced him to re-examine his own relationship with his father.

The musician was born Benjamin Gerard Coyle-Larner to a white, British mother and a black, Guyanese father who was "present at times and not present at other times" during his childhood.

Instead, he and his brother were raised in Croydon by his mum and step-father, Nik, entering music at a young age with the Mercury-nominated Yesterday's Gone in 2017.

When his girlfriend became pregnant in 2019, Carner called his dad to break the news and was shocked when he hung up the phone.

A couple of weeks later, however, he called back and offered to teach his son to drive. Their relationship was repaired, or rather rebuilt, over the course of those lessons, as Carner learned about his dad's childhood in the care system, with no role model to show him how to be a father.

"To cut a long story short, we founded our relationship in that car. It became my safe space for conversation and shouting and apologising and crying," he tells the BBC.

Allow X content?

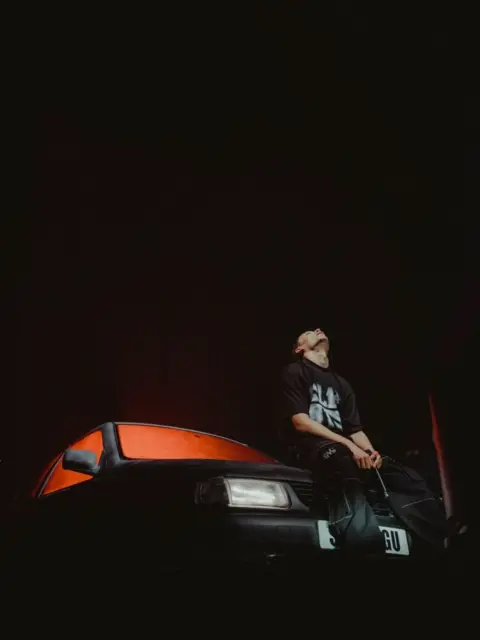

Inspired by the transformation, Carner wrote the album to commemorate those car conversations. The number plate of his dad's car, S331 HGU, gave him the album title. And it's that same car that you - and his dad who was watching at home on TV - saw on stage at Glastonbury on Saturday.

"I needed my son to know where he was from because if you don't know where you're from you don't know where you're going," Carner told the audience.

"At first I was trying to understand, I was angry, I was hateful. And over the course of these journeys, these driving lessons, I stopped talking for a second and started listening. When I started listening to my father's side of the story and understood that when my father was growing up as a black man... he didn't have the tools to love me the way he wanted to love me.

"But my mother over there, she raised me with the tools to be the father I could be for my son."

'Shakespearean'

The stage show was designed to reflect that narrative - a transition from anger and resentment to understanding and ultimately forgiveness.

"We wanted to translate that emotional story into a physical story," explains George Thomson, creative director at The Unlimited Dream Company.

"And with Ben, we arrived on the idea of using the sun as a 12-hour day cycle. So the show goes from the intense red of sunset during the first song, Hate, through the moody contemplation of night and into a new dawn that shows the new way forward in his relationship with his father."

It was an intense and hands-on collaboration.

"Even in rehearsals, while Ben's rapping perfectly, he would also be sketching and writing notes and making like colour charts," says co-creator Harrison Smith.

"He automatically thinks visually, which is why I think he's such a good storyteller."

Karolina Wielocha

Karolina WielochaHis Glastonbury set opened with the angry, antagonistic Hate, followed quickly by Plastic, a polemic about the seductive but reductive allure of consumer culture.

At his angriest, Carner performed on top of the car, bouncing aggressively on the bonnet. On the more introspective Polyfilla, where Carner questions how his flaws will compromise his parenting, he stands in the dark, illuminated only by the beam of a single streetlight.

"I treated it like a Shakespearean play where it's divided into acts, and every act has its own beginning, middle and end," Carner explains.

As on the album, he uses his personal story to explore bigger frustrations with the world.

At Glastonbury that included urging fans to "forget all that toxic masculinity... that ruined my childhood", as well as a barbed commentary on his personal dissatisfaction with the government.

After playing Blood On My Nikes, he brought out former youth MP Athian Akec, for a poignant speech about knife crime, while also praising teachers who are striking for better work conditions and pay.

"I want to speak up for teachers. I want to speak up for nurses," he tells the BBC. "I want to speak up for the people in my community. I feel a responsibility for the people that I'm around."

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBC

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBCIt's a topic he's personally connected to. Both his mum and his girlfriend work as educators, and he says some of the teachers he encountered as a child "saved my life".

"I've a lot of friends who wouldn't be here, or wouldn't have amounted to anything if they didn't have that one person to believe in them," he adds, "and I'm upset that we're not giving teachers the world.

"We treat them like they're babysitters [when] they're basically the last line of defence for so many kids who, for whatever reason, are struggling at home."

He describes the current strikes in schools and hospitals as a Catch 22 situation, that ends up hurting the pupils they're supposed to mentor.

"Teachers can't be busy fighting for themselves, they need to be fighting for the students that need their help.

"But when they don't stand up for themselves, nobody else seems to."

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBC

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBCIn lesser hands, this could easily have become heavy-handed; but Carner has a relaxed demeanour, that made his headline show feel more like an intimate conversation with a friend.

He was helped out by an impeccably funky live band - including special guest Olivia Dean - who added depth and texture to his lyrical meditations.

All those complex, intertwined frustrations and fears culminated in the set's final track, HGU - a song not just about forgiving his dad, but forgiveness and acceptance in general.

"Within rap, everyone else is like, 'If your dad left and he's rubbish, just let that anger be your motivation,'" he explained in liner notes for the record.

"That's cool to an extent, but it can cripple you if you let it go further than an initial youthful rebellion."

"You'd think a song about forgiveness would be all lovey-dovey and light," says Smith, "but it's about an active choice to forgive someone, so there's an outpouring of anger that allows you to transition to forgiveness.

"It's not a natural step. And when the audience experiences that all coming together, it's quite emotional."

Carner says it's a cathartic act to come out every night "so frustrated and broken-hearted with the way the world is going" and end in "a place of forgiveness, not only for my father, but also for myself."

"For me, it's been such a beautiful thing."

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBC

Sarah Louise Bennett / BBCOn stage, he offered his story up as an example to the audience.

"I used to carry this weight, this chip on my shoulder. I thought if I forgave my father, I'm setting him free [but] what about me?

"I didn't realise when I forgave my father, I forgave myself, I was able to love myself, look after myself, remove this chip on my shoulder."

And as he left the Glastonbury stage, forever changed, the star offered this mantra: "Take these words and go forwards".