How Eurovision became an LGBTQ+ safe space

Jamie McLoughlin/BBC

Jamie McLoughlin/BBCIt wasn't the biggest bar in the world and it was heaving, but somehow my partner and I found a seat by the farthest wall, sharing a table with a small group of Icelandic fans. When they found out we were from Merseyside, the eyes of one of them lit up.

He slipped an impressive, silver ring from his finger. "Look," he said proudly. "See what I've got engraved inside here."

Even in the half-light, the words You'll Never Walk Alone, the Rodgers and Hammerstein song forever linked with Liverpool Football Club, were unmistakable. Coupled with the drunken sincerity of his free hand reaching up to his heart, it was just as obvious how much the team meant to his Nordic soul.

It was around that moment the entire bar broke into a mass sing-a-long of The Herreys' Diggi Loo Diggi Ley, Sweden's 1984 Eurovision victor. Belted out with such booming fervour, the myriad of tiny glitterballs covering every inch of ceiling space threatened to rain down on the giddy clientele.

Forgive me for not pointing out earlier this wasn't exactly a pub full of football fans. No, this was 9 May 2014, in one of Copenhagen's gay pubs. The following night, the Danish capital would host the Eurovision final - and we didn't have a clue that, nine years later, the city bonding a group of complete strangers would also stage the extravaganza.

It's not the first, and probably not the finest, example of how the song contest has had a thoroughly supportive hand on the shoulder of the LGBTQ+ community for decades.

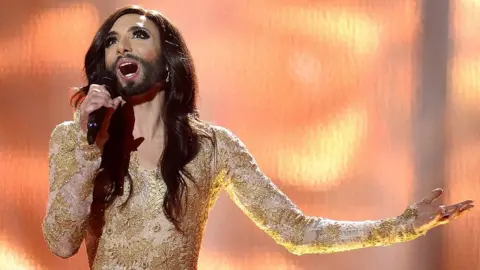

Getty Images / Jonathan Nackstrand

Getty Images / Jonathan NackstrandA day later, Austria's Conchita Wurst would soar to victory with Rise Like a Phoenix, in front of a crowd packed to the rafters with members of said community. The performance earned a reception which had the temporary seats in the converted shipyard that staged the show rattling.

With the drag persona of singer Thomas Neuwirth, the win felt like much more than first place in an entertainment show. It came less than a year after Vladimir Putin passed a law banning children in Russia from learning about homosexuality and the country's entry was loudly booed by the arena crowd, while others waved the Pride flag for the camera. Eurovision wasn't just a safe space that night, it was a defiant one.

Conchita remains one of Eurovision's defining LGBTQ+ moments, but she wasn't the first - that came 53 years earlier.

Jean-Claude Pascal, a French artist representing Luxembourg, won the 1961 Contest with the song Nous les Amourex (We Lovers). It's believed by many interpreters that the song was about a homosexual relationship, with ambiguous lyrical themes about partners facing judgement from those around them amid references to hell and irons.

A 2019 article by Belgian broadcaster RTBF took a closer examination of the text, even declaring it a protest song in favour of the gay movement, although it is never explicitly stated that the song is about two men.

Getty Images / Keystone

Getty Images / KeystoneThere was a little less subtlety in 1986 when host nation Norway fielded Ketil Stokkan, performing Romeo, with members of a drag troupe. By the time Paul Oscar of Iceland turned up in 1997 as Eurovision's first openly gay entrant, fans like myself were starting to find each other in the early internet forums.

In my early twenties, still at university and with an eye on a journalism career, one of those fledgling friendships was with another aspiring writer, Catherine Baker. While I took the newspaper path, she became a reader in 20th Century History at the University of Hull and a specialist in the post-Cold War era.

Still a huge Eurovision fan, the contest has often shaped her research into national identity and popular music during and after the Yugoslav wars. What does she see as the safe space this competition creates?

"Look at it from today's point of view, it is somewhere where all kinds of LGBTQ+ identities are present, are valued," says Dr Baker.

"It's not even newsworthy when an artist is LGBTQ+ and that itself is a huge change compared to 25 years ago when it was headline news that the first LGBTQ+ contestant was going to be performing [Paul Oscar]

"Then came the first trans contestant who became the first trans and LGBTQ+ winner, Dana International.

"That, of course, was the last time the contest was held in the UK. There's some really important history there, not just for Eurovision but actually in international trans history."

Getty Images / Peter Bischoff

Getty Images / Peter BischoffEurovision provided one of the first places Dr Baker felt able to express herself openly, when - at around the age of 16 - she found she could search for Eurovision sites in her school computer room.

"I would read websites, take part in forums, and it gradually dawned on me that, actually, probably, most of the people I was interacting with on there were gay - back then that was the main LGBTQ+ identity that people had," she explains.

"That was the first time in my life I'd been in a place that was not majority straight, in a space where you didn't have to feel cautious about what you gave away about yourself."

Internet connections paved the way for fans meeting in person. The Retro bar near London's Trafalgar Square was the spiritual home of contest fandom for many in the early noughties. In the north-west of England, I became involved in regular days (and nights) out where a majority-gay crowd of Eurovision enthusiasts would chat, drink and - occasionally - see romance blossom.

Patricia J. Garcinuno/Getty Images

Patricia J. Garcinuno/Getty ImagesThe contest has become a place that makes people feel more confident of stepping inside a predominantly LGBTQ+ space - and it's become something charitable organisations can use to help others, such as London Friend, a charity that supports the health and wellbeing of the capital's LGBTQ+ community.

Its chief executive, Monty Moncrieff, believes the draw for many is seeing themselves represented and included in one of the biggest broadcasts of the year.

"Eurovision isn't an LGBTQ+ event but it's affectionately referred to as 'Gay Christmas'," explains the dedicated contest fan.

"And I think that says a lot about how it's viewed by our community. It's a great opportunity to hold safe and inclusive events, and we've done several quizzes and preview nights as fundraisers for the LGBTQ+ charity I manage in places like the [famous drag venue] Royal Vauxhall Tavern."

Monty has even been approached by organisers for his knowledge and advice in making the contest be as safe a space as possible. For example, in 2017 he went to Kyiv on behalf of the UK fan club to help the British Embassy and British Council understand LGBTQ+ fans' concerns in the lead-up to the event.

"They did a great amount of work to offer support and reassurance we'd be safe," he says.

"Actions like this have been especially important when the contest has gone to less tolerant places. It's not always safe for LGBTQ+ travellers and this shows the [host] city has thought about this and wants to reassure us we'll be welcomed."

Anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination laws are still on the statute books in parts of Eastern Europe and though it remains challenging for people in some of Eurovision's competing nations, there are reassuring signs.

This year, Belgium's entrant Gustaph is keeping it in the family by having his husband Roen design the visuals for his '90s-esque dance anthem Because of You - a song about chosen family, the support network so many LGBTQ+ people build around themselves.

Perhaps Eurovision's goal moving forward is to foster the ultimate safe space for artists to be their true selves onstage, no matter what the laws in the country they are representing may say about them.